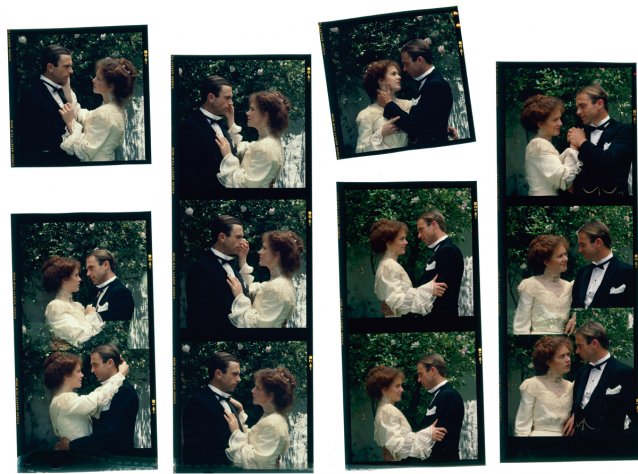

Movies shown in cinemas have come to represent the most powerful form of entertainment of our age, due to the size and diversity of the audiences they reach and their larger-than-life format. Starstruck: Australian Movie Portraits – a collaboration between the National Portrait Gallery and National Film and Sound Archive – translates and channels that movie-going experience into an exhibition, revealing how still photographic images capture the elusive quality of stardom in Australian actors, from the earliest silent films through to the cinematic fare of today. Starstruck’s striking photographic portraiture, accompanied by costumes, documents and artefacts, connects audiences with behind-the-scenes stories as engaging as those shown on the big screen, and includes distinctive thematic threads.

One of these distinct (and central) themes is the role of women in the history of Australian cinema; and, given the current revelations of discrimination against women in the entertainment and movie industries, it is an apposite one. From the 1920s onwards, women have worked at the heart of the industry, mastering and harnessing the power of celebrity, and collaborating to make exceptional films. Starstruck pays homage to an array of these women, among them the courageous 1920s film pioneer Lottie Lyell, and the creative trio behind the 1979 movie My Brilliant Career, Margaret Fink, Gillian Armstrong and Judy Davis.