The zeitgeist of an era can be captured in artefacts both grand and small. Such is the case with the innovative, ‘environmental’ style of portraiture that features in two books illustrated by Mark Strizic in 1968: 2000 Weeks, and Involvement: the portraits of Clifton Pugh and Mark Strizic. Strizic’s images broke with the period’s established style of professional portraiture, reflecting rising trends in art and magazine photography that sought to present sitters as authentic people, rather than ponderous civic fathers or impossibly glamorous society figures. There was also a change in the types of sitters captured, with creative artists and VIPs portrayed as equals, rather than in a stratified, hierarchical manner. This was perhaps part of a broader desire to present Australians as part of the ‘new world’ – with their own values and interests – rather than the old. Some of the results, however, also suggested an anxiety about identity – who and what we were as a nation.

In and out of focus

by Gael Newton, 19 December 2017

Australian film director Gillian Armstrong recently recalled her shock as an 18 year-old film student in 1968 on seeing an art house film in Carlton that had Australian voices: ‘I had never seen an Australian film. We weren’t making them.’ The lack of everyday Australian voices, faces and stories in the movies meant the medium was playing no part in fostering a modern Australian identity. Accordingly, to many among the younger generation, Australia seemed to have become a nation of consumers – rather than producers – of culture. But some were determined to do something about that situation.

Armstrong’s comments were probably in reference to Tim Burstall’s feature film 2000 Weeks, shot in moody black and white in Melbourne in early 1968. This was an Australian conceived, made and financed co-production by Eltham /Senior Films about urban life and aspirations among the thirty-something between-the-wars generation. It was heavily promoted, and characterised as ‘A New Dawn In Australian Film Production’. The film – with a plot set in contemporary (1960s) Melbourne – was offered as the alternative to a decade or so of Australian-made (but foreign-funded) films that stuck to stereotypical Australian bush and colonial themes.

Co-written by Tim Burstall and Patrick Ryan – Burstall’s patron and the director of Eltham Films – 2000 Weeks follows the story of Will Gardiner, a 30 year-old Melbourne journalist aspiring to write television drama. He has a good family life but also a beautiful young lover, Jacky, and he’s not sure where he’s going. Gardiner’s dying father challenges him to do something with his remaining 2000 or so weeks of life. The ending is unconventionally unresolved: Will is no hero; Jacky sails off to make it in London, and we have no hint of his future life.

2000 Weeks was shot in black and white with a European art house look. Released in March 1969, Robin Copping’s dynamic cinematography was praised, but the script was savaged by film critics as overly wordy and banal. Burstall thought the public just hated seeing themselves on screen. The film famously failed at the box office, but is now saluted as a clarion call for the renaissance in Australian film production of the 1970s-80 – known as the ‘New Wave’ – in which Burstall and Gillian Armstrong were central figures. Burstall did a great deal with his remaining 2000 or so weeks.

The failure of the film at the box office also eclipsed a petite 2000 Weeks ‘photo novel’, published by Sun Books as a movie tie-in in late 1968, as well as sales of the solo jazz album by Don Burrows, who had been commissioned to provide an up-to-the-minute score. Both book and recording are now rare items.

The 2000 Weeks photo novel was illustrated with stills by the film’s director of photography, Robin Copping, and official stills photographer Mark Strizic – at the time a leading Melbourne photographer. Like the film, the photo novel has an art house look and differed markedly in structure from past book-of-the-film novels or star-studded film promotion brochures. The design is an orchestrated whole with dramatic zooms, from close-up to deep perspective, and cropped details from stills graphically integrated on the pages, with floating script excerpts and a lot of blur. Similar stand-alone film photobooks didn’t appear until the 1990s, when stills photographers began exhibiting and publishing their work as part of their own art practice.

The 2000 Weeks book design reflects the dramatised graphic layout of pop culture magazines in the sixties. The images also hint at new styles of documentary art photography – with a cinematic spontaneity and offbeat composition – that would appear in the 1970s in the work of young art photographers graduating from new college art courses, such as Carol Jerrems.

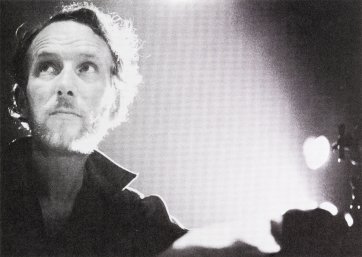

When hired for 2000 Weeks as stills photographer, Strizic was a well-established Melbourne commercial photographer, known for his architectural photography and graphic design skills. He had known Burstall since the early sixties, and was familiar with the Eltham artists’ colony where Burstall and a number of artists, including Clifton Pugh, lived. While far from being Bohemian himself, Strizic appeared to take an experimental approach with his photography that could deliver stills to match the film’s aesthetic. The photographs and layout in the photo novel are clearly ‘in sync’ with Robin Copping’s cinematography, and Strizic’s role as photographer and graphic designer for the book was critical. He also saw his stills work as but one part of his personal art practice – in February 1968, while the shoot was still running, Strizic exhibited prints from 2000 Weeks at The Age building, including his atmospheric on-set portraits of Burstall and Patrick Ryan.

Indeed, 1968 was to be a heady year for Strizic’s artistic evolution, as well as for the arts generally, with the new Australia Council for the Arts opening in Sydney, and the National Gallery of Victoria’s building being constructed on St Kilda Road. Its strikingly modern design (by Roy Grounds) put Victoria at the top of the art museum world. While Strizic was working on set for 2000 Weeks he was concurrently (from January to March) fulfilling a commission from businessman and arts patron Andrew Grimwade to photograph 41 of the sitters painted over the course of the previous 15 years by Clifton Pugh, a fashionable portraitist. It was quite an undertaking, even if many sitters were Melbourne-based.

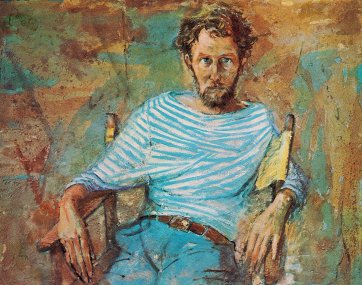

Strizic’s portraits were paired with colour reproductions of Pugh’s paintings in a hefty, deluxe art book with embossed leather cover titled Involvement: the portraits of Clifton Pugh and Mark Strizic. Published in late 1968, it was a limited edition release comprising 1200 signed copies. Grimwade, who thought of Pugh as a great artist, conceived, managed and paid for the project, which included sending Strizic to London, Munich and New York to photograph a number of the sitters. The publisher was, again, Sun Books, an affordable paperback press founded in 1965 to promote Australian writing. Both 2000 Weeks and Involvement represented a departure from their usual fare. The Involvement sitters were varied, from captains of industry to self and family portraits, although they were mostly male. It was quite ‘old-fashioned’ in some respects, yet also reflected the period’s new interest in books about Australians and Australian artists, rather than promotions of Australia.

Andrew Grimwade conceived the title for the book to convey the idea that portraiture was an engagement between sitter and artist, but also that artists engage with each other. Strizic’s rather painterly graphic style – having been refined in recent years on industrial commissions – was well matched with Pugh’s painted portraits, which featured a satisfactory level of likeness and even a kind of photographic gaze, as in Kate Hattam from 1956, with its colourful semi-abstracted patterns. Commentaries from the two artists on how each portrait was made gave a glimpse into their sitters’ characters as well as their own vision and process as artists. Writer and Sun Books editor Geoffrey Dutton provided the introduction, and argued vehemently that photography made by a creative talent like Strizic was an art. However, despite the equal billing in the imprint, Strizic’s pictures play second fiddle to the tipped in colour plates of Pugh’s paintings. The photo portraits are small images (of only medium reproduction quality) on the left hand caption pages. It was, nevertheless, radical – at the time – to present photography as in any way analogous to painting.

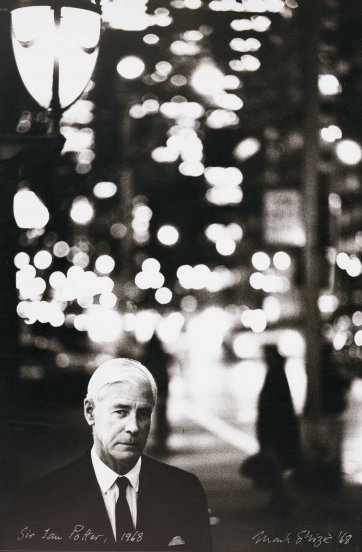

Strizic’s film and commissioned portraiture for 2000 Weeks and Involvement employed a ‘contrasty’ graphic style, often with offbeat 35 mm framing with a ‘snapshot’ spontaneity that he had been exploring since the early 1960s. Strizic’s rather cinematic technique saw his sitters glimpsed almost secretly through blurred foreground objects, or against dappled backdrops and into the light, causing flare. He embedded the person in their environment – artist-craftsman Matcham Skipper for example, is seen through the wrought iron screens he was completing for the entrance to the Australian National University’s HC Coombs building; and merchant’s son turned cattle-breeder Douglas Carnegie is seen at work in the feed shed from the viewpoint of one of his Herefords. Businessman and philanthropist Sir Ian Potter’s head and shoulders are seen at the bottom of the image, against the blurred lights of Times Square, where Strizic was sent to photograph him for the book.

As fellow photographer Werner Hammerstingl noted in Strizic’s 2013 obituary, ‘His virtuoso compositions, that often have the lens practically touching an object in the foreground, make wonderful use of an extremely shallow depth of field. This approach was practically the opposite of conventional practice, and highly original.’ Hammerstingl was referring to the kinds of static, often heavily lit portraiture in vogue since the 1930s, and characterising the photography of Strizic’s older competitors in Melbourne and Sydney, such as Athol Shmith and Max Dupain. Strizic – ten or so years their junior – had taken a more innovative and spirited approached to portraiture.

The 2000 Weeks photo novel sank with the film, and Involvement received mixed reviews from critics. Patrick McCaughey and Beatrice Faust were dismissive of Strizic’s portraits as ‘tricky’, rather than moving. With the exception of Nobel Prize-winning scientist Frank McFarlane Burnett, shown in a casual, almost snapshot view at his desk – complete with bottle of Clag glue in foreground and garden behind – the sitters preferred their painted portraits.

In May 1968 Strizic’s exhibition Some Australian Personalities – a portrait exhibition derived from his 2000 Weeks and Involvement commissions – was held at the National Gallery of Victoria, then housed in the Verdon Gallery of the State Library. It was the last show before the Gallery’s relocation to the new St Kilda road venue later that year. This is regarded as the first solo photographic art show at the National Gallery of Victoria, which subsequently moved to open a photography department. Strizic sold a portfolio of these portraits as a body of work to the National Gallery of Australia in 1972 – the first photographs to enter the National Collection.

Sun Books’ 2000 Weeks photobook was a forecast of the heavily manipulated photo-based murals of Mark Strizic’s later years as a painter-photographer. His 1960s professional work offered some of the first innovations in professional portraiture for decades and, as photo-historian Martin Jolly has noted, contributed to the imagining of a more contemporary vision of Australian identity.

Related people

Related information

Portrait 58, Summer 2017-18

Magazine

Paul Cézanne, Bill Henson and Simone Young, Australian cinema’s iconic women, and feminist portraits by Kate Just.

Drawing inspiration

Magazine article by Dr Christopher Chapman

Christopher Chapman absorbs the gentle touch of Don Bachardy’s portraiture.

Of beef in burgundy

Magazine article by Angus Trumble

Angus Trumble reveals the complex technical mastery behind a striking recent acquisition, Henry Bone’s enamel portrait of William Manning.