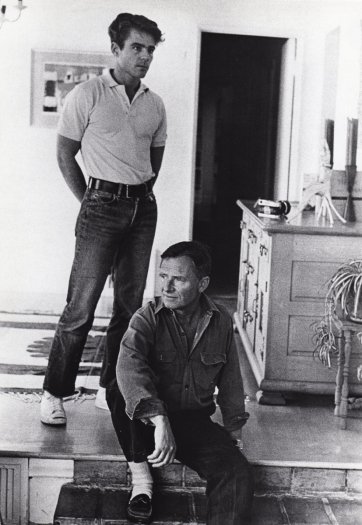

The delicate line that characterises the portrait drawings of American Don Bachardy translates careful observation into the feeling of gentle touch. In an interview with Christopher Harrity in 2014 for The Advocate, Bachardy, then aged 80, recalled the communicative facility of touch with reference to his life partner, the novelist Christopher Isherwood. ‘We slept very close together, entangled.’ Mornings saw the couple on the deck of their Los Angeles home, regularly reflecting on ‘the latest night together and what awareness we had of each other in the night’. Together until the end of Isherwood’s life in 1986, they met when Don was a boyish-looking Californian teenager of 18 and British-American Christopher was a celebrated author aged 48.

Drawing inspiration

by Dr Christopher Chapman, 19 December 2017

Isherwood has written of the importance of friendship between men, where an older mentor offers a younger man ‘serious interest, advice, encouragement’. The nature of friendship was important to Isherwood. In his memoir, he wrote: ‘Nevertheless, when a male friendship includes sexual love, I dislike referring to either of the friends as a “lover” or a “boyfriend”. Except in the plural, “lover” suggests to me a one-sided attachment; “boyfriend” always sounds condescending and often ridiculously unsuitable. So I shall go on using “friend” and try to show what the word means when applied to any given pair of people.’

Certainly, for Christopher and Don, friendship meant steadfast faith in each other, and Christopher encouraged Don in his portraiture. Don had drawn since his childhood – his mother Jess would take Don and his brother Ted to see Hollywood movies; the brothers hunted autographs and Don made portrait drawings from photographs in movie magazines. Film actors became a principal portrait subject. ‘As a younger portraitist you have to draw famous people,’ Don told Harrity, ‘otherwise how will the public at large be able to tell whether I can get a likeness? It has to be somebody recognisable.’

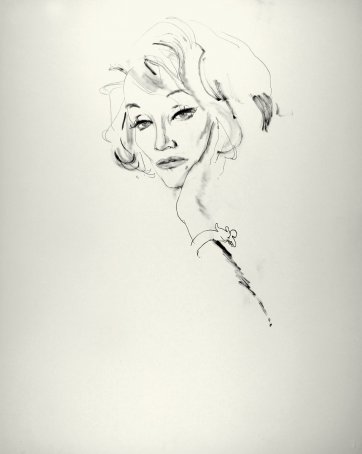

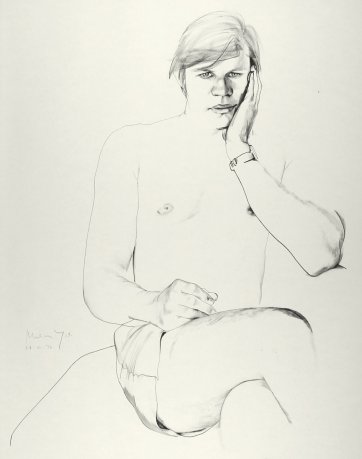

Don’s deft lines define the salient features of Marlene Dietrich, Natalie Wood and Jane Fonda in his portrait drawings from 1963: Dietrich with wily, sleepy eyes; Wood’s face youthfully clear; Fonda’s features signalling contained energy. Michael York in 1972 – portrayed cross-legged in a pair of shorts – has a solid physicality, broad nose and flat nipples, weighty thighs and fleshy lips. As rendered by Bachardy, glowing translucency defines York’s presence.

Early in its life, the National Portrait Gallery purchased from his then London gallery three portrait drawings of female actors by Bachardy. His portrait of Dame Judith Anderson is sinuous – she appears reticent, reserved. The Adelaide-born actor’s portrayal of Medea in the 1947 Broadway production of the Greek tragedy won her a Tony Award. Pulitzer Prize-winning New York Times drama critic Brooks Atkinson described as ‘inspired’ the ‘rage and revenge’ she personified in the role, written for her by poet Robinson Jeffers. For Alfred Hitchcock’s 1940 drama Rebecca, Anderson was nominated for Best Supporting Actress at the Academy Awards. The film won Best Picture.

Googie Withers was the first non-Australian woman to be made an honorary Officer of the Order of Australia (she was born in Karachi to a Royal British Navy captain father and Dutch-German mother). Bachardy captures a sparkle that might have reflected the actor’s learned second nature – she had performed in at least 50 films and television dramas when the portrait was made in 1962.

His mid-1970s portrait of Melbourne-born Coral Browne suggests an inward-looking aspect of character. The evolution of Bachardy’s style towards a softer line is evinced in her unfocused, pensive gaze. The portrait of Browne, who – like Anderson – was drawn by Bachardy when aged in her sixties, also conveys an elusive suggestion of her psyche. Browne lived in England and then the USA; the actor Vincent Price was her second husband. In the 1970s and 1980s, she received several ‘Best Actress’ awards for television, film and theatre in both countries.

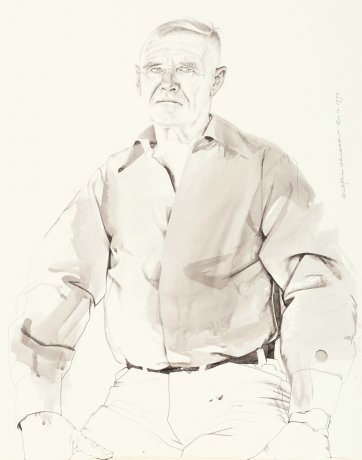

Bachardy went to London in 1961 to study at the Slade School of Fine Art and had his first exhibition at Redfern Gallery that year. He deeply missed Isherwood. Later, the two collaborated as writers on a screenplay for I, Claudius, to be directed by Tony Richardson. In September 1969 they travelled to Australia to visit Richardson, who was filming Ned Kelly (with Mick Jagger in the lead). They stayed at Palerang Station homestead near the NSW town of Braidwood, and spent a Sunday at a Braidwood pub. ‘Although this country seems relatively law-abiding, far more so than the States,’ Isherwood wrote of the trip, ‘there is much more of a frontier feeling’. There were ‘Crowds of beer-drinking men. Men everywhere. The women much less in evidence.’ Around Palerang, he noted, ‘the endless empty silence, the pistol-sharp crack of grey, dead gum-tree wood, the foreign squawking of birds’. In Bachardy’s portraits, Isherwood holds a contemplative expression, projecting a sense of relaxed acquiescence to life.

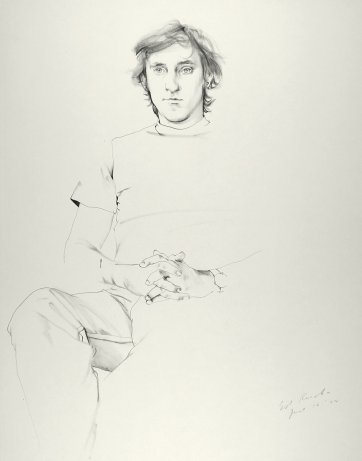

For the portraitist who brings subjects to life through the mechanism of finely wrought drawing, observation requires a special sensitivity to the physical, an attuned bodily awareness. Bachardy’s depiction of individual personhood through drawing evokes the subtlety of physical touch (his painted portraits and male nudes are robustly expressionist with psychological heat). His drawing style is precise; there are hints of the ethereal when needed, along with a rarefied psychological insight. That is how, in his portrait drawings of Los Angeles artists from the mid-1970s, he is able to interpret and convey the single-minded intellect of his subjects. Inherently attractive in their youthfulness, Bachardy sees their glowing lucidity: Larry Bell’s profile is framed by the curly hair of a Caravaggio boy; Chris Burden’s wispy beard is like that of an adolescent; Ed Ruscha’s handsome face is a sign of the American masculine identity typified by young Jack Kerouac. In Bachardy’s drawings, he renders boyish Vija Celmins and Alexis Smith, ‘minority’ females in this masculine art scene. I see affinity with the sensations of the male body, coupled with a projection of a familiar male psyche in Bachardy’s drawings of men. Here, for me, is evidence of recognition honed through sustained self-examination, with the self-portrait as a tool for building self-reflection.

In his self-portraits, Bachardy often fixes a demanding glare. I would characterise this as the searching gaze that signals the desire to know oneself continually and intimately, to pay close attention to one’s face and body over time. This is attention to the manifestations of febrile energy or tiredness resisted, to the gleam of satisfaction or flicker of doubt, to the fine calibrations of thought – revealed and concealed through the face – that are identifiable between close family and friends, and with one’s confidantes.

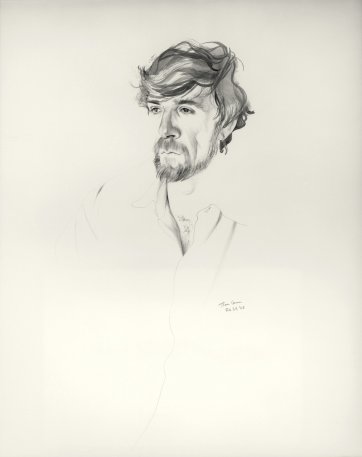

Bachardy’s late 1960s portrait drawing of British-American poet Thom Gunn, held by London’s National Portrait Gallery, shows Gunn aged in his late thirties, all angular features and luxurious hair. Gunn seems to be contemplating his own self; he seems to be thinking, ‘how is it that I am this person now?’ Gunn would eventually use his poetry to reflect on the emotional stakes of physical contact and connection between men, and to echo the elegies for gay men who died from AIDS during the virus’ 1980s peak. His early poems translated his specifically homosexual psychological understanding into universally accessible themes. Moving to America in 1954 to be with his US Air Force officer partner Mike Kitay, Gunn used the word ‘you’ instead of ‘he’ in his love poems. He guarded his homosexuality. Had he come out then, Gunn told interviewer James Campbell, he ‘would never have got to America’, ‘would never have got a teaching job’.

I had almost reached the circumstance where my own coming out took place, when a good friend gave me a worn ex-library copy of Gunn’s slim volume of poems, My Sad Captains, of 1961. ‘They were men who, I thought, lived only to renew the wasteful force they spent with each hot convulsion’, the title poem’s central lines whisper. Jay Parini wrote that the poem was Gunn’s ‘farewell to the past’. It was ‘a tender yet fiercely self-critical piece’, says Parini, ‘a resolution to approach life and art from now on with greater flexibility and humaneness’.

Since adolescence, affection conditioned my connection with close male friends. Allegiance was based on what I would now call ‘intellectual intimacy’ (through which I was invited to share in knowledge of certain record labels, for example). Throughout the 1980s and into the 1990s I yearned to be able to love my ‘best friends’, to hold them close. All the while, I maintained the necessary protections that had been a survival method since childhood. My true self was camouflaged. When he gave me Gunn’s book of poems 30 years after they were first published, did my friend know that Gunn was gay? Why then would our friendship evaporate when I came out to him? Had the closeness of our friendship, its emotional intimacy, suddenly appeared as ulterior or disingenuous? Time and place, the attitudes of family and friends, the real or perceived risks to personal wellbeing always influence coming out. In my twenties, I battled with myself. I, too, distanced myself from gay friends because of my own fear of association. The thrill of coming out was followed by years of sublimated resentment. I blamed society for denying me language to guide the discovery of my real self, an ‘insult’ that, as Didier Eribon puts it, ‘lets me know that I am not like others, not normal’. (Eribon also calls upon philosopher Michel Foucault’s 1976 reflections on his self-discovery as homosexual: ‘for those from earlier generations,’ Foucault says, ‘it was a kind of magic, the day you realised that that is what pleasure was, and at the same time there was the feeling that you were marked, the black sheep’.)

Aged in his seventies, Thom Gunn pointed out to interviewer Christopher Hennessey ‘do I think self-discovery or self-knowledge is an important part of my work? Yes.’ Poetry, Gunn said, invoking the words of his ‘old teacher’ Yvor Winters, ‘is an attempt to understand – not that one can succeed in understanding, but the attempt to understand’. Gunn told Hennessey his poem ‘The Allegory of the Wolf Boy’ (written when Gunn was 26 or 27 and published in 1957) can be understood as representing the first stage of coming out. The poem was inspired by a story he had read at age 14 (by Hector Hugh Munroe, who used the pen name ‘Saki’) about a ‘werewolf who was a boy’. Clive Wilmer, in his notes to Gunn’s Collected Poems, says Gunn ‘confirmed in conversation that the poem was about growing up as a gay youth and feeling compelled to live a double life’. For Gunn, the poem ‘struck me as a marvellous allegory of sexuality – all sexuality – being covered over by clothes,’ he told Hennessey, ‘and desire, the wolf, coming over the person who is very reluctant to acknowledge but can’t help acknowledging it’. The poem’s last stanza reads:

‘White in the beam he stops, faces it square.

And the same instant leaping from the ground

Feels the familiar itch of close dark hair;

Then, clean exception to the natural laws,

Only to instinct and the moon being bound,

Drops on four feet. Yet he has bleeding paws.’

I can imagine that in his portraits of Thom Gunn, Don Bachardy is recognising someone who is like himself. He is looking with a depth of understanding, based on shared emotional and psychological experience. How is this apparent in the drawings themselves?

The deftness, the lightness of style that Bachardy brings to his portrait drawings is how he sees his subjects, how he translates their physicality and psyche for us. A complex multitude of interests, experiences and artistic exploration informs Bachardy’s artistic style. This is what characterises his work, as every artist’s own pursuit of ‘understanding’ characterises their own.

Related people

Related information

Portrait 58, Summer 2017-18

Magazine

Paul Cézanne, Bill Henson and Simone Young, Australian cinema’s iconic women, and feminist portraits by Kate Just.

Of beef in burgundy

Magazine article by Angus Trumble

Angus Trumble reveals the complex technical mastery behind a striking recent acquisition, Henry Bone’s enamel portrait of William Manning.

Hump days

Magazine article by Jessica Bolton

Jessica Bolton navigates the parallel tracks documenting Robyn Davidson’s astonishing journey.