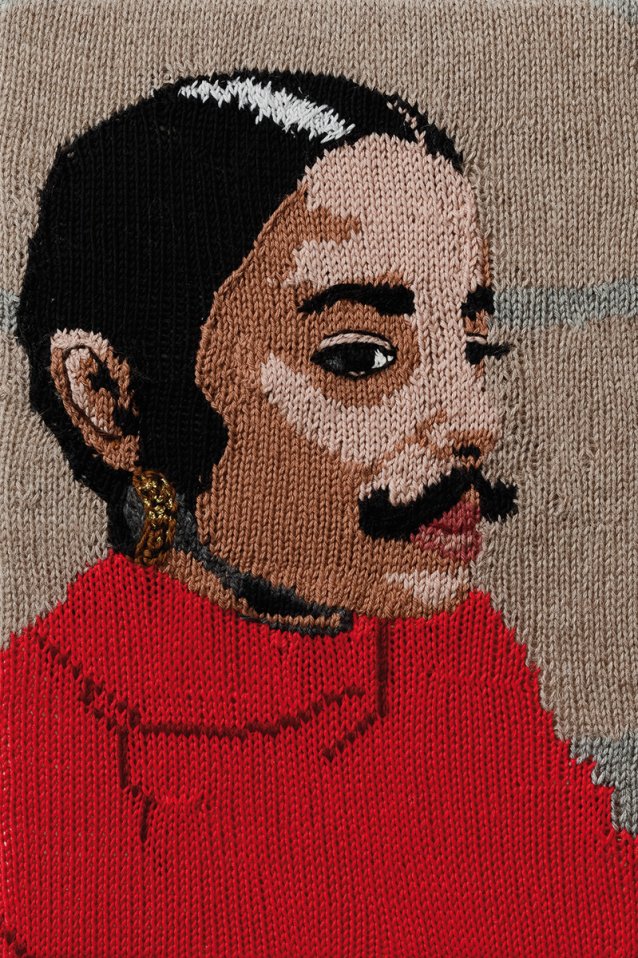

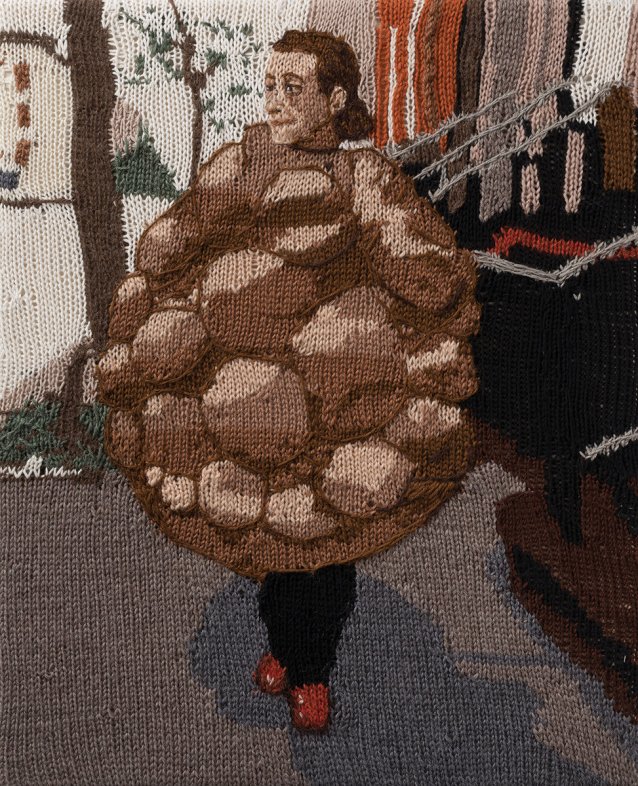

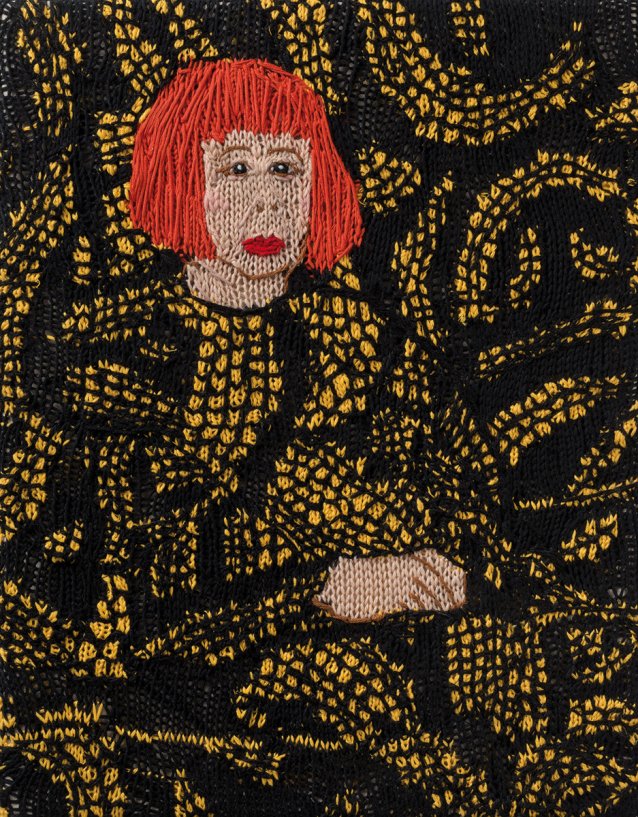

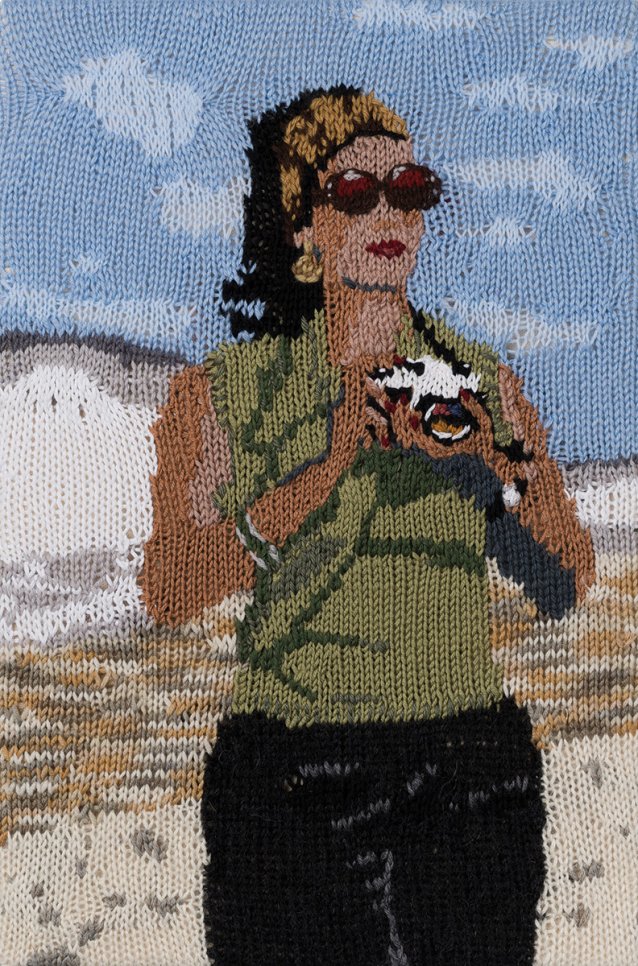

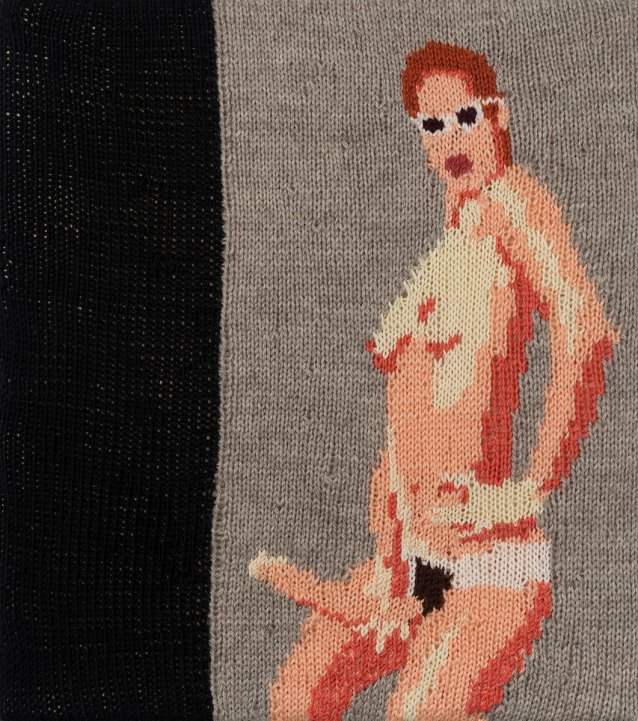

Feminist Fan is an ongoing series by Melbourne artist Kate Just. Each work is a hand-knitted homage to a self-portrait or artwork by a feminist artist around the globe. The title of the series emphasises Just’s reverence of the artists and feminism, and each carefully rendered picture – featuring over 10,000 stitches and 80 hours of work – constitutes an act of devotion. As a collection, Feminist Fan forms an intimate family portrait of feminism and Just’s influences, in which threads of connection between artists and across time and cultures emerge.

How did you come to develop the Feminist Fan series?

The idea for this series started with me collecting photographs and images of artists working with ideas of ‘craftivism’ and the public space, as well as activist groups like Pussy Riot [Russia] and Femen [Ukraine] doing action in public spaces with their bodies as a provocative and disruptive force. Femen were doing these photos of themselves naked with text all over their bodies to make political commentary, while Pussy Riot had done the performance in the church. When Pussy Riot was imprisoned, Casey Jenkins and some other artists in Melbourne had organised a protest, and I had this photo of Casey holding a sign that said ‘PUSSY’ on the steps of Parliament House.

As I was collecting these materials I thought it was so interesting that there was this real moment of women putting their bodies on display for political effect. The next thing I thought was, ‘what would it look like if I knitted some of these pictures?’ The first one I knitted was Casey at the Pussy Riot protest, followed by Femen at the Hague.

At first I thought they didn’t look really good at all. But then slowly they started growing on me, and then strangely by the third or fourth one in I switched my focus and started collecting images of female artists from the 1970s like Carolee Schneemann and Lynda Benglis, and thinking actually that these things are quite closely connected. I think it’s always been part of feminism to use the body as a provocative force, whether in public, in a performance, or in a photograph. So I thought – what would happen if I connected them? What would happen if I put Casey, Pussy Riot, Carolee and Lynda together in one canon? So that’s how it happened over a period of time.