I spoke with Henson on the phone earlier this year, 2017, soon after his exhibition of work made between 2008 and 2011 opened as part of the National Gallery of Victoria’s Festival of Photography. I also caught up with Young briefly on the phone for her reflection on her portrait all these years on. Now based in Sussex, England, and in demand to conduct orchestras around the world, Young was in Australia in July conducting a performance of Messiaen’s Turangalîla Symphonie with the Australian World Orchestra and the Australian National Academy of Music.

Bill Henson grew up on the outskirts of Melbourne and his first solo exhibition was at the National Gallery of Victoria; it featured 40 works focussing on the dancers’ faces at a ballet school in 1975. He was 19. By 1998, Henson had over 50 solo exhibitions behind him, including representing Australia at the Venice Biennale in 1995. He does very few commissions.

Simone Young grew up in the northern Sydney suburb of Balgowlah. She was 24 when she started her operatic conducting career – a 1985 performance of The Mikado at the Sydney Opera House, with Opera Australia. 1986 saw her named Young Australian of the Year and taking a position with the Cologne Opera in Germany, before joining the Berlin State Opera. She has conducted at the Vienna State Opera, the Bastille Opera in Paris, Covent Garden, the Bavarian State Opera and the New York Metropolitan Opera, among many others.

Both Henson and Young knew they shared a love of German Romantic opera, and this connection between musician and listener constituted the foundation of the relationship between sitter and artist. Henson says his listening habits are careful, serious and deliberate. As with poetry and literature, classical music is absorbed into Henson’s way of seeing and representing the world: ‘I often listen to music as a means of helping me clarify what I think I should be doing in a picture’, he explains. ‘It’s something that I’ve always done.’ Henson’s work intrigued Young, and she was familiar with his Paris Opera project.

One challenge with commissioning portraits of contemporary relevance involving two artists in the midst of extraordinary creative lives is chancing upon the moment they can meet. Between 1998 and 2002, Young served as the Chief Conductor of one the world’s oldest orchestras – dating back to 1765 – Norway’s Bergen Philharmonic. During this time Henson had seven solo shows, including exhibitions in Zurich and Los Angeles, with his work also being included in 17 group exhibitions. Finally, the opportunity to realise the portrait commission arose between 2001 and 2003, when Young was Artistic Director and Music Director of Opera Australia.

It was a day in early 2002 when Young visited Henson’s studio in Melbourne. The photographer had set up the lighting; Young dressed as she would for a performance. Henson put Der Rosenkavalier on his studio record player and asked her to conduct it. Henson remembers Young exclaiming at the time, ‘It’s going to be very strange!’ Miming to a recording is very difficult because it is the opposite of what a conductor really does. Young had never attempted such a thing before. A conductor leads the orchestra, prompting, ‘instigating’ the music, and knowing ‘what you want the next half-second to sound like’ as Young described her work in a recent interview. For his part, Henson recognised that conducting to a recording might feel somewhat bizarre, artificial. Young, however, understood Henson’s premise – to use the music to inspire her to move the way she would when conducting a late Romantic German opera.

Der Rosenkavelier – ‘The Chevalier of the Rose’ – is a story of love, seduction and intrigue in which a silver rose serves as a symbol of impending matrimony. Later that year, Young was to conduct Strauss’ opera to open Opera Australia’s spring season. In the days before that performance, in conversation with Radio National’s Andrew Ford, Young reflected on the opera as a ‘masterpiece of humanity’ and described the opera’s central character Marschallin as ‘an incredibly contemporary woman’. ‘She’s a great humanist, she’s a realist, she’s a woman of extraordinary generosity of spirit.’ Appropriately, similar themes pervade Henson’s practice, with intimacy, humanity and the human condition at its heart.

Both Henson and Young remember that they almost got through the whole (three-hour-long) opera, Young standing on a box conducting as Henson moved around her with his camera. ‘I think she went into a bit of a zone, and just kept going, which is what I wanted.’ When making his work, this ‘zone’ usually involves Henson giving thousands of very precise instruction to his models in a silent studio. This time it was Kleiber – a legendary Austrian conductor who had been dead for over 50 years – directing, as Young worked with music that she knew note for note. ‘It was quite intense’, she remembers, ‘to be very honest for the camera … to make this work, so it was actually quite exhausting and quite challenging’. ‘I could have kept shooting and shooting’ says Henson. ‘She was completely exhausted. So was I. We shot a lot of film and that was it. We packed up, and I think we might have had a drink and then off she went. And it was over.’

Back in 1998 when Sayers proposed the commission, Henson had immediately realised he was going to face the same challenge with this portrait as he’d had with his Paris Opera Project: that of photography’s evidential authority. In 1990 the Paris Opera commissioned Henson, giving him free reign to choose his approach and subjects. With a subject embedded in time and reality, the photograph, by its nature, records and documents. Henson both uses and subverts this, making objects that themselves have a space and time – a distinct reality. ‘To introduce a kind of an artificiality is the

only way to achieve that’, explains Henson. The final project was 50 works, including landscapes, cloudscapes and the ‘audience sitting in the dark … with the light raking across their faces, absorbed in the music’, as he later described it to Janet Hawley for the Good Weekend magazine. However, they were not the actual audiences, but images inspired by Henson’s observations of Paris Opera audiences, then recreated by models in Henson’s studio.

Similarly, Henson created Young’s portrait in his studio. He explains that ‘through that artificiality or kind of unreality, theatricality, that you can jump over that reportage aspect of photography while retaining that authentic … emotional content and intellectual engagement’. Together, Henson and Young committed to enacting this essence of a conductor in performance in a sublime and generous – almost enchanted – creative moment. The portrait does not document or depict Young conducting – it is Young conducting.

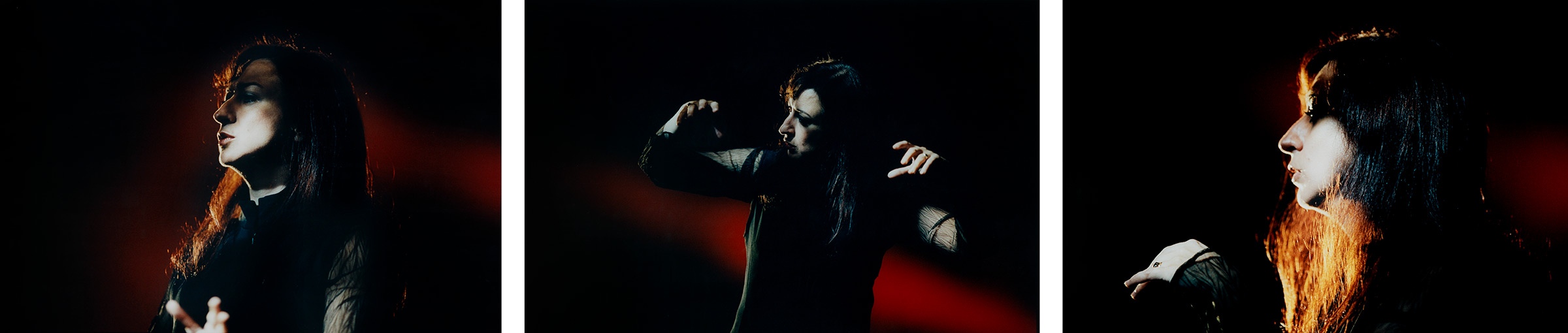

After the unusual studio session, Henson spent many months in the normal course of his process: going over the negatives, looking and thinking. He does not digitally manipulate his images. He does his own printing. During this time, Henson resolved the triptych structure and size of the portrait. The work consists of three parts, each measuring 104 x 154 centimetres. Henson speculates that the structure might refer back to his work of the early 1980s – triptychs and diptychs that investigated ‘the way in which things fragment and then coalesce’. The structure becomes a ‘dynamic space … and each part a fragment of the whole’, with fractured, colliding moments of time anchored by symmetry. As with all Henson’s work he is, in his words, ‘trying to suggest some psychological space, to open up some space of the imagination’. He wants his work to take the viewer on unexpected journeys of the imagination, to open possibilities and provoke wonder. It is ‘that sense of something that you can’t quite reach, but that you can feel or sense’ that for Henson makes a work compelling. ‘You experience a photograph with your whole body, not just with your eyes or intellect, Henson tells me. ‘It’s not about being big or small, it’s about being right.’

Henson’s work is often described as painterly, cinematic, enigmatic, mysterious and ambiguous. His portrait of Young is no exception. ‘I was interested in the way great music affects us. The sheer force of such beauty causes us to fall in love. It is that love that I wanted to see transform the subject’s appearance’, Henson told the Gallery in 2002. It is a reflection entirely consistent with the dramatic, passionate, late Romantic spirit of Der Rosenkavalier. As with all Henson’s work, it is hard to be conscious of the work as a photograph: the light rakes across Young’s face as movement or brushstrokes, illuminating her complete absorption in the music. The instigating, directing, leading power of her hands flows through her arms and shoulders as they vanish into the deep red dark. Astonishingly, the portrait captures that sense of the conductor being half a second ahead of the music in her mind.

Of seeing the final portrait, Young tells me, ‘I was so proud … I think it is incredibly beautiful and actually quite moving … to be the subject of this portrait was a tremendous honour and a privilege.’ For Young, the structure is ‘very operatic. It’s like three acts of an opera or three movements of a symphony.’ In a 2002 interview with the Sydney Morning Herald’s Lisa Pryor, Young spoke of the formality of the first act, melodrama of the second act, and serenity of the concluding act. For Henson, this musician’s reading of the work ‘makes perfect sense’, but ‘it’s not something that I thought of’. This is a sign of the portrait’s success in transcending its medium and embodying the music that lies at the heart of Young’s presence, achievements and being.

When I ask how the portrait fitted into his ongoing practice, Henson explains that he carries with him the experience of making each picture in a ‘gradual accretion’. In 2005, he collaborated with Richard Tognetti and the Australian Chamber Orchestra on Luminous, a project where a series of works and a musical performance appeared in concert, without one ‘illustrating’ the other, but rather in tandem, forming a coherent work. The same year, the Art Gallery of New South Wales staged a major Henson survey show of over 350 works. 2005 also saw Young become Artistic Director of the Hamburg State Opera and Music Director of the Hamburg Philharmonic Orchestra (HPO). Over the following ten years, she led a workforce of 700, including a 128-piece orchestra and 70-strong voice chorus. During her tenure (as one of HPO’s longest serving directors) there were over 500 performances and 50 new productions, including ground-breaking contemporary repertoire.

Although she has lived mostly overseas since the portrait launched, Henson’s work remains a presence in Young’s life, with friends and family sending her messages after visiting the Gallery. Looking back at the portrait now, Young observes, ‘like any fine work of art, it has a life, it has something to say beyond a particular time and beyond a particular occasion.’ When I ask if there was anything else she would like to tell me about the portrait, Young’s response is earnest: ‘Just that it was truly exceptional ... I don’t expect I will ever experience anything quite like that again.’

The story behind Bill Henson’s portrait of Simone Young captures an essential quality of great portraiture: the depth of imaginative understanding between artist and sitter, unconscious and untapped until that fortuitous moment when creative lives, art and minds meet during a sitting. On a quiet day in the Gallery, you can almost hear Young’s imagined orchestra sitting in darkness during a momentary pause in the opera she will now forever conduct.