The National Gallery of Art in Washington DC is a massive, marvellous place and easy to get lost in – so much so that you end up coming across treasures unexpectedly and in unexpected places, as was the case when I visited in late February 2017. A pompous equestrian portrait of George Washington in a stairwell, for instance. A display of works by Dutch photographer Rineke Dijkstra in an unassuming space near the lifts. And a gem of an exhibition of twentieth-century American prints installed in two modest rooms just inside the 7th Street entrance. Comprised of a mere 25 works, The Urban Scene: 1920–1950 presented a detailed portrait of everyday life in American cities. It showed crumpled folk on subway carriages; faceless citizens on the breadline; skyscraper construction workers and peak hour pedestrians; people sitting on stoops; women waiting for washing to dry. In etchings, lithographs, wood engravings and aquatints, the represented artists observed their subjects with sensitivity and precision, utilising a deft handling of light and shade to convey ordinary, often insignificant scenes and the varying moods of the modern metropolis. It was, its curator explained, an exhibition of pictures by artists who are not household names and whose ‘non-canonical’ status is partly attributable to their choice to work in an illustrative, realist mode that – in the face of bleak or hard-nosed modernism – found difficulty firing or sustaining the art-historical imagination.

Nocturnal animals

by Joanna Gilmour, 19 December 2017

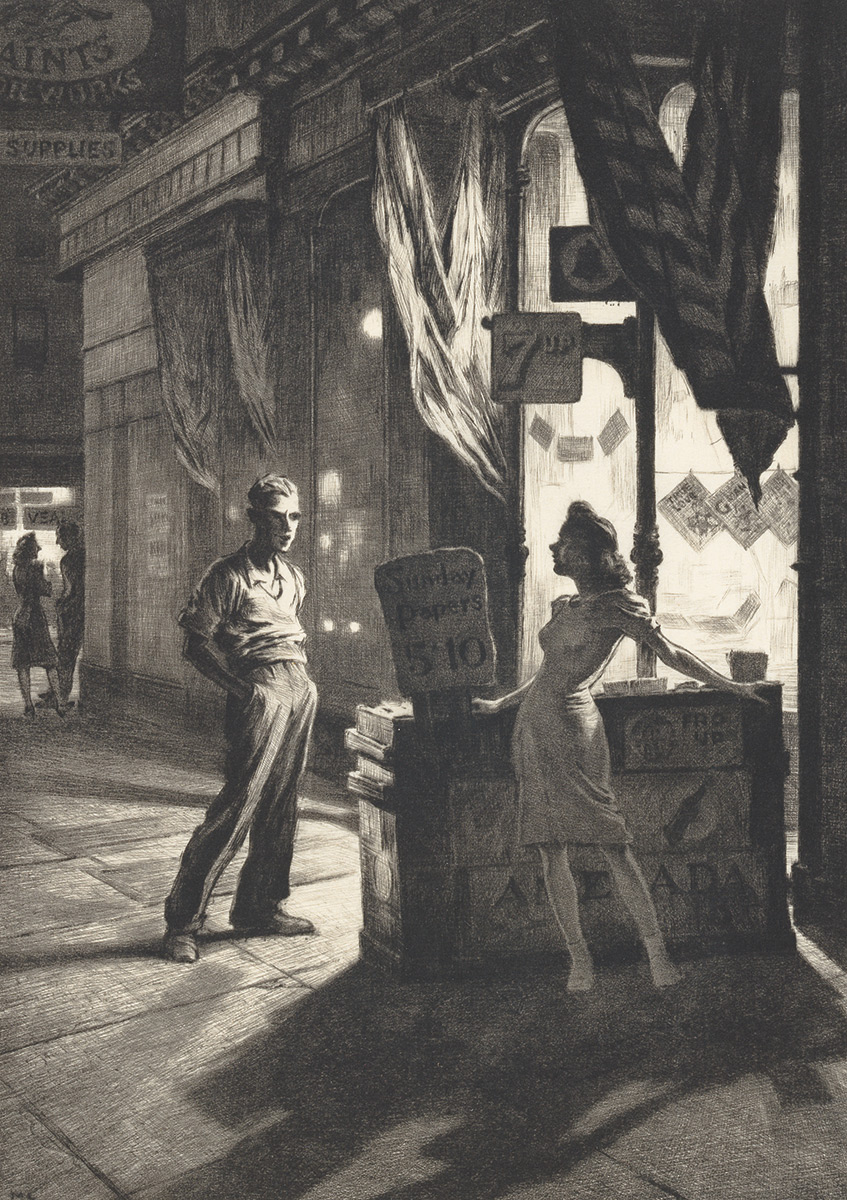

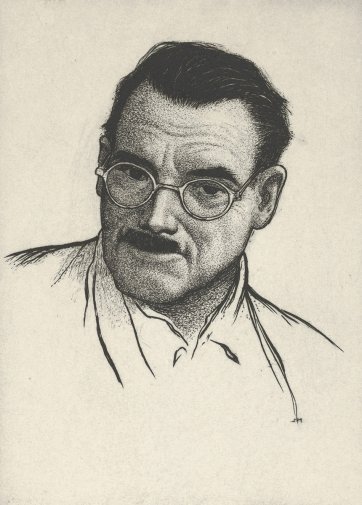

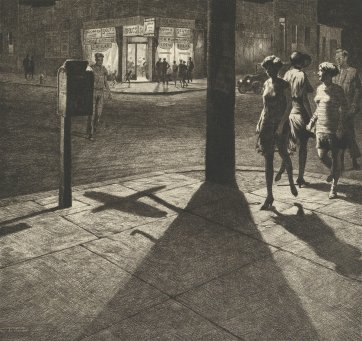

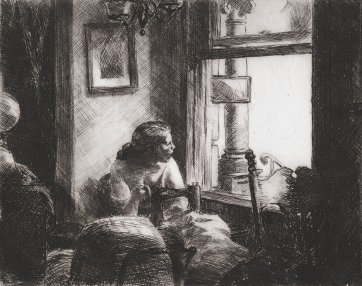

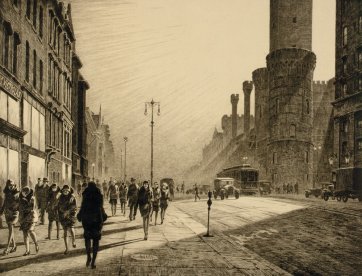

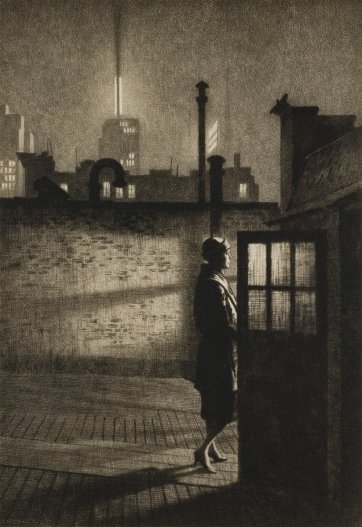

The Australian-born printmaker Martin Lewis (1881–1962), one of the 22 ‘American’ artists whose works formed the exhibition, is a case in point. An expert in etching and drypoint, Lewis enjoyed a period wherein he was praised as ‘the most psychological interpreter of American life as it is lived in New York’, having produced a series of images which are highly evocative of the city in its inter-war years. In Glow of the City (1929), for example, a woman with bobbed hair and a drop-waisted dress gives herself a twilight airing on a tenement fire escape, the Art Deco Chanin Building incandescent in the distance. Corner Shadows (1926) features various iterations of after-dark congregations, with a gathering outside a corner establishment’s bright lights, foreground pedestrians in motion, and the hint of intimacy in a distant couple. And the film noir-ish East side night, Williamsburg Bridge (1928) suggests a commonplace, momentary encounter between two strangers who happen to be in the same place at the same time.

‘Few artists know New York so intimately or thoroughly,’ stated the American Magazine of Art of Lewis in April 1930 ‘and none has caught so well the spirit of this terrifying and enchanting city.’ Perversely, though, the ‘sincerity and directness’ with which Lewis depicted the city, and his almost exclusive application to the graphic medium, contributed to the decline of his career. Compared to the grit and alienation characteristic of the urban vignettes etched by his friend Edward Hopper, Lewis’ perceptive observations – sometimes amusing, sometimes unsettling, consistently empathetic – can appear almost too quintessential. According to the New York Times in 1998, ‘at his best, [Lewis] was a wonderful illustrator and chronicler whose vision of the city rings true; at its least, his work is a kind of corny urban regionalism’, purportedly lacking the originality necessary to earn the distinction eventually conferred on Hopper and other American contemporaries.

Lewis was born in Castlemaine in 1881 and is said to have run away from home at age 15. After four years of ‘scrambling for a living at whatever work offered’, he settled in Sydney, where he worked as an illustrator, fell in with a bohemian set, and took lessons at Julian Ashton’s art school. These classes and the training he’d had in drawing at the Castlemaine School of Mines in the mid-1890s are believed to have constituted his only formal tuition in art. Having had two cartoons published in the Bulletin, Lewis worked his way to the United States as a merchant seaman around 1900, spending time in San Francisco and Chicago before eventually settling in New York in 1909 and finding work as a commercial artist. It is through this work that he is believed to have met Hopper, who sought instruction from Lewis in the etching process.

While some art historians have said that the technical assistance Lewis provided Hopper was rudimentary, others cite Hopper’s acknowledgment of Lewis’ influence on his work. Either way, the parallels between Hopper’s early career prints and Lewis’ later, rigorously accomplished etchings are obvious, with both artists being drawn to the medium’s potential for the manipulation of shadow and tone, and hence its fluency in communicating the solitary, brooding and complex temperament of the city at night. Lewis’ prints of the late twenties and early thirties were a critical and financial success, with whole editions of certain images – such as Relics (Speakeasy Corner) – selling out, and the response to his 1927 and 1929 solo exhibitions at Kennedy & Co, a long-established Manhattan specialist in American art, prompting him to prioritise printmaking over commercial work. By 1932, however, the Depression had begun to impact the print market and Lewis moved to rural Connecticut, where he remained for four years. Though he continued to make prints, Lewis struggled to reclaim attention after his return to New York in 1936, and in 1944 he took up teaching to support himself. The subsequent emergence of Abstract Expressionism – and the relish with which it was embraced as uniquely American – consolidated the eclipsing of artists like Lewis and their intimate, realist scenes of urban life. Whereas Hopper’s early output as a printmaker is celebrated for being his method of experimenting with the themes and compositions he continually returned to in his later, now canonical paintings, Lewis’ prints have, for much of the time since his death in 1962, been somewhat unknown outside his adopted home. In recent decades, Lewis’ comprehensive portrayal of New York has increased in estimation for its contribution to twentieth-century visual culture, and as a subtle and alternative, yet equally potent, vision of American modernity.

Related information

Portrait 58, Summer 2017-18

Magazine

Paul Cézanne, Bill Henson and Simone Young, Australian cinema’s iconic women, and feminist portraits by Kate Just.

In and out of focus

Magazine article by Gael Newton

Gael Newton looks at Australian photography, film and the sixties through the novel lens of Mark Strizic.

Drawing inspiration

Magazine article by Dr Christopher Chapman

Christopher Chapman absorbs the gentle touch of Don Bachardy’s portraiture.