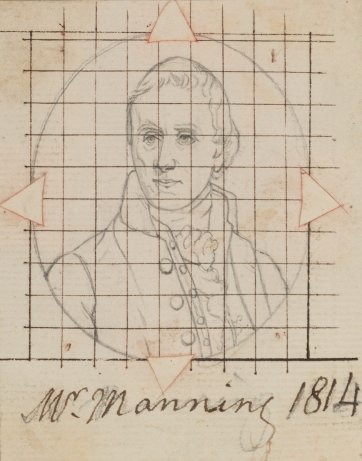

In 1824, William Manning MP (1763–1835), together with 27 other Members of Parliament; the Governor, Deputy Governor and eight other directors of the Bank of England (including Manning); and the Chairman, Deputy Chairman and five other directors of the Honourable East India Company joined forces and formed in London the Australian Agricultural Company. By its élite composition this consortium effectively formed one of the most ambitious and important pieces of private enterprise in the early history of colonial New South Wales. It was, in turn, almost certainly prompted by the successful establishment of Singapore by Sir Stamford Raffles in 1819: a free port under British control that thenceforth linked East India Company possessions (in India, Ceylon, Burma and parts of modern Malaysia) to the Australian colonies, and also to China and the trans-Pacific trade. In a sense, we are today only beginning to realise the full potential.

The following year, through the Governor of New South Wales (Sir Thomas Brisbane), the Australian Agricultural Company formally sought the advice of his Surveyor-General, John Oxley, about suitable land in which to invest. Oxley duly sent Henry Dangar, a surveyor employed by the Company, to assess the region stretching between Port Macquarie and Port Stephens. On this expedition, Dangar named the Manning River after William Manning, who was by then Deputy Governor of the Company. The Company soon extended its reach to the area around Tamworth. In due course it opened the first railway in Australia, and established a virtual monopoly on coal mining around Newcastle. However, cattle grazing for the production of beef has long since been the company’s main focus. It continues to prosper.

Manning was the son of a West India merchant and planter on St Kitts and Santa Cruz (today Saint Croix in the US Virgin Islands). William joined his father’s firm and took it over in 1791. He inherited two thirds of his mother’s estates on Santa Cruz and purchased the remaining third. He was an official agent for St Vincent from 1792 to 1806 and for Grenada from 1825 to 1831. He became the leading advocate for the West India interest in the unreformed House of Commons, where he represented Plympton Erle (1794−96), Lymington (1796−1806), Evesham (1806−18), Lymington again (1818−20; 1821−26), and Penryn (1826−30). More importantly, Manning became a director of the Bank of England in 1792. He went on to be Deputy Governor from 1810 to 1812 and then Governor from 1812 to 1814, right in the middle of the crucial ‘Restriction Period’ when the bank issued £1 and £2 notes to stop the drain on gold bullion that was caused by the high cost of the Napoleonic Wars.