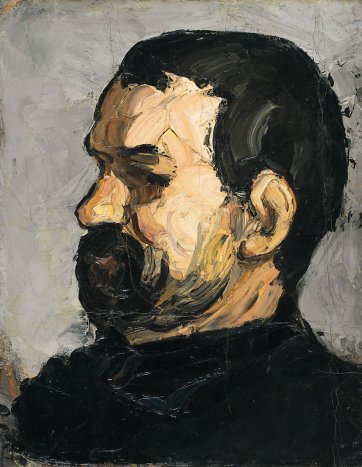

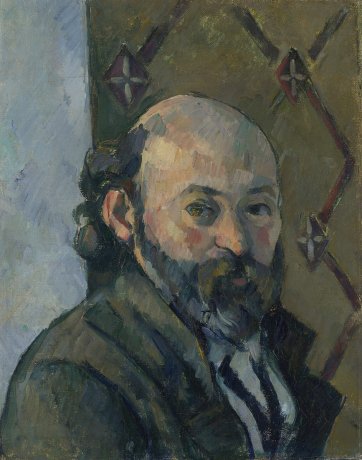

Portraits by Paul Cézanne (1839–1906) have appeared in virtually all retrospective surveys of his work, beginning with the first such exhibition at the Paris Salon d’Automne in the year after his death, an exhibition that was decisively influential on artists who saw it, including Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso. Nonetheless, surprising though it may seem, the exhibition currently showing at the National Portrait Gallery, London is the only exhibition exclusively devoted to Cézanne’s portraits since 1910, when Ambroise Vollard, who had been the artist’s dealer, showed in his Paris gallery twenty-four ‘Figures de Cézanne’.

How is this possible? Over a working life of some 45 years, Cézanne made almost 1,000 paintings, of which around 160 are portraits. This is far fewer than his 320 landscapes, but not many fewer than his 190 still-lifes; and more than either his 130 figure compositions or his 80 paintings of bathers. So why has it taken so long for his portraits to be given the attention they deserve?

The answer, in short, is that Cézanne’s reputation, as it developed in the early decades of the twentieth century, was as someone who had transformed Impressionism into a newly objective, classical art that paved the way for modernist abstraction. This interpretation meant that more attention was paid to style than to subject matter, and, therefore, that Cézanne’s paintings of mute objects and natural scenes – still lifes and landscapes – were thought to be more central to his achievement than his paintings of actual, individual people. His paintings of bathers had to wait until 1989 to get their due (with a great exhibition at the Kunstmuseum, Basel), but their subjects are generic figures, which do not provoke the same questions that the portraits do: ‘Who are these people, and why did Cézanne paint them?’ as well as ‘Why did he paint them in the way that he did?’

In fact, many early critics played down the function of these portraits as records of the appearance of distinct individuals, treating them as no different to his still-life paintings. True, Vollard reported that, when he began fidgeting while sitting for his portrait, Cézanne said to him, ‘You wretch! You’ve spoiled the pose. Do I have to tell you again you must sit still like an apple? Does an apple move?’ But that did not mean that he was treating his dealer as if he were a piece of fruit. What now seems so extraordinary about such portraits is how their pictorial inventiveness and their vivid depiction of human presence are mutually reinforcing. To demonstrate that is one of the most important aims of the present exhibition.