Tom Wills was forty-four years old when he met a pointless, violent death in circumstances a far cry from the propriety and comfort of his beginnings. His death certificate gave his occupation as ‘gentleman’, yet he had for some time been subsisting on an allowance and the odd additional contribution from his brothers, and died in the rented house he shared with the woman who referred to herself as his ‘wife’ even though their partnership had never been formalised. With his domestic arrangements already the cause of shame to a respectable family, Wills added further insult through dying by his own hand at a time when many God-fearing, upright types saw suicide as sin, a deep moral flaw along the lines of cowardice and other varieties of disgraceful, unspeakable behaviour. The coroner’s finding that Wills ‘killed himself when of unsound mind from excessive drinking’ spared his family the further shame of a verdict of willful ‘self-slaughter’, but reiterated the ignominy of the condition that had so utterly undone the career of a man once numbered among the most illustrious Australian sportsmen of his era. First-hand accounts of Wills’s death make disturbing reading, describing how, in a state of delirium tremens and having absconded from Melbourne Hospital, he ‘possessed himself of a pair of scissors, with which he stabbed himself, inflicting three wounds on the left breast, immediately in the region of his heart’.

Born in Sydney in August 1836, Thomas Wentworth Wills was the eldest son of Horatio Spencer Wills (1811–1861), a landowner and erstwhile newspaper proprietor whose father had been transported to New South Wales for highway robbery in 1799. Named for his father’s good friend (and lawyer), William Charles Wentworth, Tom was not quite four years old when he took part in the journey by which Horatio relocated from Burra Burra, his holding on the Molonglo River, to the Port Phillip district in late 1839. The following year, Horatio selected a 120,000 acre run just east of the Grampians, the traditional country of the Djab Wurrung people, where the next five Wills children were born and where Tom, seven years older than his nearest sibling, made mates with the local children, picking up their language and developing an affinity that persisted, irrespective of the role of distant Aboriginal people in the tragedy that later claimed the Wills family. Insistent that his sons should receive the sort of education he’d never had, in 1846 Horatio sent Tom to Melbourne to the school established by the Oxford-educated William Brickwood ‘for the instruction of youth in the usual branches of Classical, Literary, Scientific, and Mercantile education’. At Brickwood’s, Tom made his first, albeit inauspicious, foray into cricket, scoring a duck in both innings of an intra-school match in September 1846. When his schooling in Melbourne finished three years later, it was decided that he would benefit from the instruction offered by an English public school, and at fourteen Tom was duly bundled ‘home’ to Rugby so that he might be further equipped for ‘the duties of the learned professions … or of the gentleman.’

It was, however, as a sportsman and not a scholar that Tom came to distinguish himself at Rugby School, his disinclination for the cultivation of his intellect being apparent from the outset. In August 1851, he wrote home admitting that ‘I have not been working hard enough to please a saint’, excusing his lack of application to study in claiming that: ‘One thing I know is that it does not please my health, I have been ill oftener the last 4 or 5 months than I have been for the last 6 or 7 years. I know that if I work too hard that I will become quite ill. We hardly get any play during school time’. Horatio’s sister, Sarah Alexander, living in London with her merchant husband and with whom Tom spent his summer holidays, considered her nephew to have been ‘very backward when he arrived in England’ in 1850, later instructing Horatio that ‘it would not be advisable to take him from school for some time yet … he has much yet to learn which could not be acquired with much ease and advantage as at present, when no other occupation interferes to attract his attention’. They were famous last words. By this time, May 1854, Tom had already proved himself in athletics and taken up the school’s own brand of football. To boot, his cricketing prowess was such that he’d taken 104 wickets and scored in excess of 800 runs in the space of one season (in 1851), graduating to the Rugby School XI the following year and to its captaincy three years later. In August 1854, aged eighteen, Wills made his first class cricket debut, taking a five wicket haul in bowling for the ‘Gentlemen of Kent’ against the ‘Gentlemen of England’ in Canterbury. On finishing school in 1856, Wills played further games for Kent, the Marylebone Cricket Club and for Cambridge University, managing the latter without ever actually being an undergraduate in spite of his father’s hope to the contrary. ‘Remember that everything you do is for yourself’, Horatio had vented to his eldest son in 1853 on receipt of an unsatisfactory school report. ‘If you do not succeed in life and obtain the reputation of a clever gentlemanly fellow, no one will be to blame but yourself’.

Perversely, Tom had managed to obtain the reputation of a gentlemanly fellow in certain respects, embracing the demeanour and the practices that came with the club, the pitch and the pavilion, so ubiquitous was the association between sport and booze, and so customary the assumption that agreeable chaps would partake of it. Accordingly, it was as this variety of gentleman – and not the learned professional envisaged as the product of such a prestigious education – that Tom returned home to Victoria late in 1856. Again proving a disappointment in terms of solid employment prospects, he continued to pay greater attention to his on-field exploits and the congenial company that came with them, the last few years of the 1850s seeing the start of his association with several cricket clubs, including Melbourne and Richmond, and also seeing him make his first appearance as a member of the Victorian cricket squads that lorded it over bitter rivals New South Wales in seven of the ten intercolonial contests played throughout the next decade.

In 1858, Wills made the contribution to Australian sporting history that has since arguably eclipsed any of his cricketing achievements, writing in July to Bell’s Life in Victoria with his proposal to form a football club as a means of keeping cricketers fit during winter. ‘Rather than allow this state of torpor to creep over them, and stifle their now supple limbs, why can they not, I say, form a foot-ball club, and form a committee of three or more to draw up a code of laws? If a club of this sort were got up … it would keep those who are inclined to become stout from having joints encased in useless, superabundant flesh’. Having subsequently coordinated several experimental football fixtures, Wills laid the groundwork for the formation of the Melbourne Football Club in May 1859 and led the ‘committee of three or more’ that, in an East Melbourne hotel three days later, set down the ‘code of laws’ for what later became known as Victorian or Australian Rules football. A modified version of the style of football Wills adopted at Rugby, in recent years some have also advanced the suggestion, an unproven and contentious one, that certain elements of the code might be owed to marngrook, a traditional indigenous game involving a possum-skin ball, and which Wills may have witnessed as a boy.

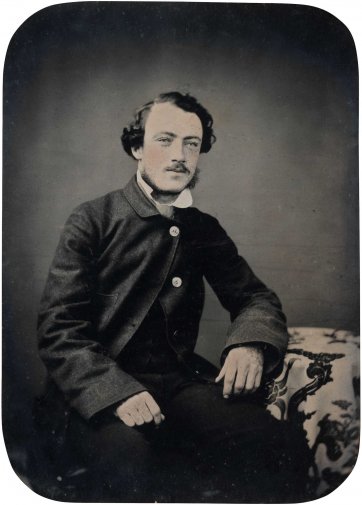

It’s this Tom Wills we see in portraits. The squatter’s son, equally au fait with the bush and the city, the scrub and the club. Urbane, handsome, sportsmanlike. A tad raffish, rough around the edges, yet at ease with clever, gentlemanly, like-minded fellows. He can be seen, for example, in EL Robinson’s 1858 lithographed souvenir of ‘the recent trial of prowess between the rival cricketers of Victoria and New South Wales’, and in Edward Gilks’s souvenir of the 1860 intercolonial match, wherein Wills took nine wickets, bowled 24 maidens, and conceded a mere 39 runs from 183 balls. Then there is the Tom depicted in the series of cased family photographs taken around the same time, and which provide evidence of Tom’s origins in industrious, self-improving colonial stock, families that in classic ‘pulling-oneself-up-by-the-bootstraps’ fashion had escaped humble, ex-convict or bog-standard origins, achieving wealth or position, or both, through speculation, enterprise and hard graft. Cased photographic portraits – daguerreotypes and ambrotypes – were, on the one hand, a personal, tangible, astonishingly real transcription of a loved one’s features, and on the other, a typical way in which one might record rites of passage, and material and social success.

Correspondingly, places like mid-nineteenth century Victoria, riddled with gold and flush with cash, attracted artists, and for some of them, Geelong, close by to where Horatio and his substantial family resided from 1852, was just as pleasing and promising a prospect as Melbourne. The state’s second most significant port had become, by the mid-1850s, the entry point for those on their way to the Ballarat goldfields and the exit point for the shiploads of wool grown in the Western District on vast holdings owned by men like Horatio. It was thus substantial enough to provide work for artists, especially those whose stock in trade was a facility in the depiction of houses, horses and self-made men. From the late 1840s onwards, Geelong appears to have been on the itineraries of various travelling photographers, and within a decade it was possible to procure a top-notch daguerreotype or ambrotype from one of several established local studios. There was, for instance, the business operated by French-born ‘Daguerrean Artiste’ Amand Auguste Fortune La Moile from a chemist’s premises in Yarra Street, where painter Robert Dowling was employed to hand-tint photographs in 1854; or the ‘rooms’ occasionally occupied by Launceston photographer H. Husband, who in 1853 offered his Geelong clients ‘coloured daguerreotype portraits in the best style’. In 1856, Joseph Turner advertised his studio on Ryrie Street as being ‘fitted up expressly for taking portraits, either on silver plates by the daguerreotype, or on glass by the new collodion process’. Eugen Willhelm Ernst de Balk, active in Geelong from 1858 and Turner’s successor as the proprietor of his ‘Portrait Gallery’ on Moorabool Street, styled himself ‘Photographer to His Excellency the Governor’; while Charles E Johnson, who arrived in Geelong by way of Cleveland, San Francisco and Melbourne in 1855, touted a studio furnished ‘in such a manner as to combine both comfort and elegance; a separate dressing room being appropriated for Ladies’. Whether any of these was responsible for the photographs of Tom, his father and siblings is yet to be determined. But what is known is that they would have been taken around the time that Tom’s brothers Cedric, Horace and Egbert (then only nine) were about to be sent to school in Germany, and before Horatio announced his departure from Geelong and the state parliamentary seat he’d held since 1855 so that he could take up his lease on Cullin-la-ringo, his new wool-growing venture in central Queensland. Unsettlingly, and inadvertently, they are portraits which secure the features of proud and fortunate folk whose blessings were soon to be blighted irretrievably.

Tom was among the group of 26 who left for Cullin-la-ringo in February 1861. Overlanding from Brisbane, they reached the station eight months later, Horatio exclaiming ‘Cullin-la-ringo at last!’ in a letter to his wife Elizabeth (who’d just given birth to their ninth child) written on 6 October. Much taken with his ‘magnificent station’, Horatio wrote of constructing fences and pens, ‘on one creek, I think called Spring Creek, alone 25 to thirty thousand sheep in fair seasons could be well kept’, he enthused. Less than a fortnight later, Horatio was among the nineteen members of his party murdered when a group of Aboriginal people camped nearby mounted a violent raid on the property. A stockman who’d managed to avoid being seen reported the atrocity soon afterwards, initiating a period of swift and thorough reprisal against the local indigenous people. Tom, who with three others had been sent by his father to a neighbouring station soon after the party had arrived, was one of the few survivors of the tragedy. His reaction, it can be easily imagined, was initially one of desolation and vengeance, but he remained at Cullin-la-ringo nevertheless, running the station until his brother Cedric (1844–1914) eventually took on this responsibility – Tom, suspected of managerial ‘irregularities’, having resorted even more to alcohol as a method of quelling the demons occasioned by the circumstances of his father’s death.

Back in Victoria permanently by 1864, Tom returned to sport and in 1866, despite the violence of sentiment he had a few years previously expressed in regards to Aboriginal people, was engaged as the captain-coach of a cricket team formed of indigenous men who’d learned the game while working as stockmen on properties in western Victoria. Members included Johnny Mullagh (1841–1891) and Johnny Cuzens (d. 1871), who both later played professionally with Melbourne and were part of the squad that went to England (the first team of Australian cricketers to do so) in 1868. Between 26 and 28 December 1866, Tom’s team played a match at the Melbourne Cricket Ground, the Argus reporting that ‘the interesting nature of the match drew together a large concourse of spectators’. Alerted to their profit-making potential, Wills helped conceive plans for an English tour, taking them on a series of warm-up performances in regional Victoria and in Sydney. The plan was abandoned when the team’s backer embezzled its funds, and amidst publicly-made observations on the questionable issue of ‘interesting’ Aboriginal players being exhibited for white commercial gain. Displaced as captain for the tour that eventuated in 1868, Tom’s declining financial form was underlined when he joined the Melbourne Cricket Club in 1867 as ‘tutor’, a title deftly disguising the matter of his slump from gentleman status to that of a professional; that is, someone who could not afford to play for mere sport. The arrangement, recorded in William Handcock’s famous portrait of Wills in MCC colours (gifted to the club by former Test cricketer and MCC secretary Hugh Trumble in the 1920s), continued into the early 1870s, during which period Tom also played football for Geelong and represented his state again in intercolonial cricket. By this time, his form and reputation, gentlemanly or otherwise, was waning too. In the intercolonial match against New South Wales in March 1872, he was called for chucking (his bowling action having long been considered suspect), and in his final representative outing, in 1875, he failed to take a wicket in a demoralising 195-run defeat. With the prospects of earning a professional living getting slimmer, Wills slipped further into debt and drunkenness, in his late years playing the occasional game of club cricket, umpiring, and serving the Geelong Football Club in administrative roles before ultimately leaving Geelong for Melbourne again in 1878. ‘I should be glad to get news from you sometimes’, Wills wrote to his brother Horace in March 1880 from his final home in Heidelberg, ‘I’m out of the world here and the only news I pick up is from the newspaper and that’s been full of nothing lately but electioneering business’. Being isolated, skint, and no longer the stuff of scoreboard legend, had a magnifying effect on a sense of diminished substance, resulting in early May 1880 in his suicide.

In reporting his death, it was the norm for newspapers to identify alcoholism only as the culprit. The Bendigo Advertiser, for instance, stated that his drinking was a consequence of the popularity earned in his ‘halcyon days of success’, the hero-worship often assuming ‘the shape of about the most ill-judged kindness that could have been offered to one of Tommy’s temperament. ... The great fault of Wills was that he had not the moral courage to say “No” ’, it lamented. Another obituary made reference to his having ‘latterly given way to a fatal indulgence’, and the Melbourne Evening Herald declared frankly that grog, ‘the curse of these colonies – the demon which has desolated so many homes and blasted the fair fame of thousands – got its hold upon him’. Recent scholarship, however – notably the biography by Sydney psychiatrist Greg de Moore – points to the fall from grace of the so-called ‘Grace of Australia’ as being attributable also to factors much darker than the longstanding partnership between booze, sport and spectatorship, with the psychological impact of the events and aftermath of October 1861 initiating what might be considered now as an affliction akin to post-traumatic stress. Such a condition could never have been anticipated around 1859 when an unknown photographer secured Tom's features at the peak of his gentlemanly and sporting glory.