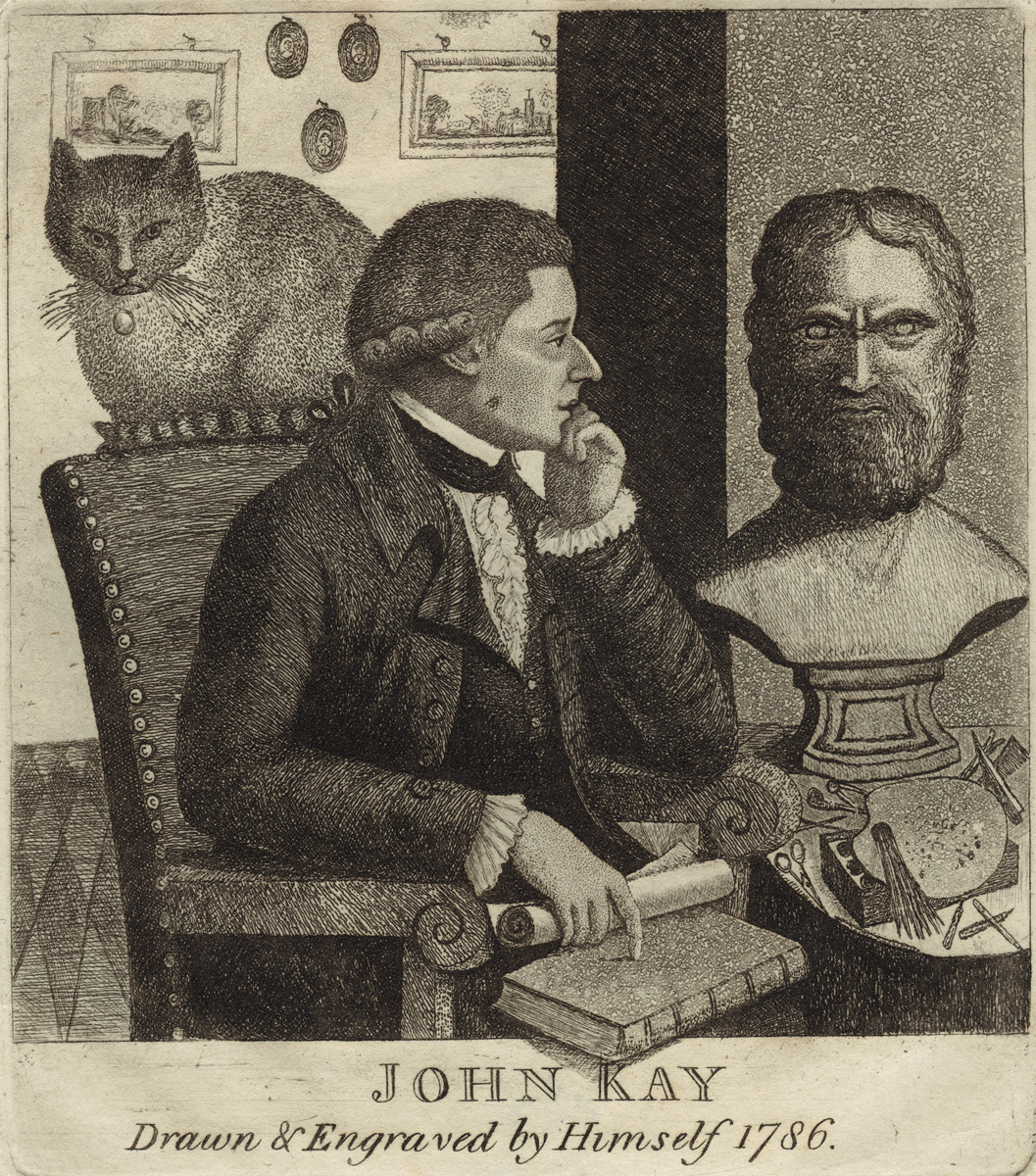

In the opinion of the author of one early twentieth century history of Edinburgh, the printmaker and miniaturist John Kay was something of an aberration within the city’s high-minded cultural tradition. Kay, being entirely self-taught, produced works ‘of negligible artistic merit’ which were rightly defined as cheap, quaint and curious and unfit for ‘public galleries and private houses throughout the country’. By this measure, upheld by art history for several subsequent decades, Kay’s work was classified as inferior for its modesty, simplicity and frankness, and for being created amidst what one scholar has described as the ‘raucous satirical vigour’ characterising the visual culture of the Georgian age.

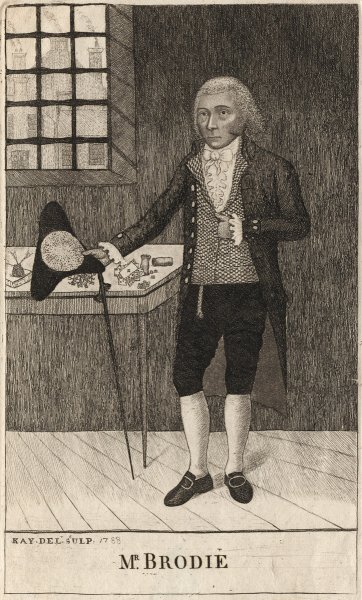

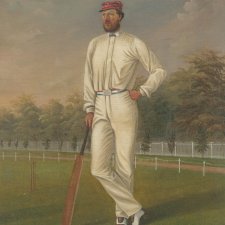

A prolific artist whose career spanned some six decades, Kay (1742–1826) started his working life at age thirteen as an apprentice to a barber in his home town of Dalkeith. At nineteen he moved to Edinburgh to continue his trade, joining the association of barber-surgeons and around the same time beginning to create caricatures of local notables and identities. He exhibited his work in his barbershop until 1785, when an annuity from a patron enabled him give up barbering altogether. Kay engraved around 900 plates, depicting ‘every figure of note in Edinburgh at that period … except Robert Burns’, and selling his work from his print room in Parliament Close. Kay often chose his subjects from among the political, social and professional elite, and it is said that some of his best customers were those whose likenesses he had rendered most objectively – and hence unflatteringly – his subjects allegedly buying his prints specifically for the purpose of destroying them. Kay’s oeuvre included absurdly buxom and ridiculously coiffured ladies; pompous, corpulent gents; and military types bristling with braids and hubris. The unseemly sectors of society attracted Kay’s attentions too, with the courts and the scaffold providing an abundant source of subject matter. Consequently, in addition to courtesans, actors, quacks and street people, it is via Kay’s mischievous etchings that the features of some of the era’s higher-profile criminals have been preserved. Take William Brodie (1741–1788) a cabinetmaker hanged for theft in 1788. A guild leader and the occupant of a lucrative position on the city council, Brodie’s upstanding-man façade concealed his nefarious behaviour. During the 1780s he became inured to the ways of burglars, recruited a gang from cockfighting dens and proceeded to plunder various places – among them the Royal Exchange, the University of Edinburgh (he pinched the college mace), and several Golden Mile goldsmiths. In 1788, authorities curbed Brodie’s depredations by offering a pardon to any gang member willing to give evidence against him. Two accomplices caught in a botched robbery duly turned informer, and Brodie and his partner-in-crime, George Smith, a Cowgate grocer, consequently stood trial in Edinburgh in August 1788. Sentenced to hang, Brodie supposedly contrived to cheat death by wearing a steel collar, bribing the hangman to ignore this impediment to the noose and arranging for friends to rescue him from the gallows. This, unsurprisingly, failed but rumours of Brodie’s escape persisted as folklore for some years afterwards.

Occupying the more sympathetic area of Kay’s output are the likenesses of Australia’s first political prisoners – Thomas Muir, Joseph Gerrald, Thomas Fyshe Palmer, Maurice Margarot and William Skirving – the so-called ‘Scottish Martyrs’ transported to New South Wales for sedition in 1794 and 1795. Muir (1765–1799), perhaps the best-known of them, was introduced to radical thinking while at Glasgow University, and as an Edinburgh-based lawyer became involved in the activities of reformist societies that, emboldened by the ideals of the American and French revolutions, were advancing such causes as freedom of speech, universal (male) suffrage and parliamentary reform. A skilled orator, Muir helped establish the Edinburgh Society of the Friends of the People, and was affiliated with various other organisations anathema to a government paranoid that certain Britons might attempt to convert their countrymen to the ways of revolutionary France. Muir was hardly the firebrand some thought him to be, but in a volatile climate even holding progressive beliefs might be construed as treason, and Muir was consequently arrested when he read out an inflammatory address at a British reform society convention in December 1792. Gerrald (1763–1796) and Margarot (1745–1815), both Londoners despite the ‘Scottish Martyr’ appellation, were the London Corresponding Society’s delegates to the convention; while Skirving (d. 1796) was its secretary. The fifth of them, Palmer (1747–1802), a Cambridge-educated clergyman, had moved to Scotland in the 1780s and in Dundee was introduced to one George Mealmaker (1768–1808), a weaver, member of the local chapter of the Sons of Liberty, and the author of a potentially seditious handbill. Printed by Skirving, this handbill became the cause of Palmer’s misfortune when he was arrested in relation to it in 1793. Though testimony (including Mealmaker’s) proved his offense to be nothing other than causing the document to be printed, Palmer was tried and sentenced to seven years’ transportation, arriving in Sydney with Muir, Skirving and Margarot aboard the Surprize in October 1794. Gerrald faced trial later, eventually making it to Sydney in late 1795 after several months in Newgate and suffering from an advanced case of tuberculosis.

Mealmaker’s political activity continued unabated. In 1794, he was questioned, but not charged, on suspicion of being involved in conspirator Robert Watt’s plot to seize Edinburgh Castle and overthrow the government – the offence for which Watt (c. 1768–1794), an erstwhile wine merchant and another of John Kay’s subjects, was later hanged and beheaded. In 1796, Mealmaker got involved with the clandestine Society of United Scotsmen, writing their constitution, publishing The moral and political catechism of man, and causing to be distributed various other subversive tracts. This caught up with him in November 1797 when he was found guilty of sedition and exiled ‘beyond the seas’ for fourteen years. By the time Mealmaker got to Sydney, in late 1800, Gerrald and Skirving were dead, Skirving succumbing to his illness (at Palmer’s house in Sydney) a few months after he’d arrived. Muir was dead too, having successfully petitioned governor John Hunter (another Scot) on the injustice of his situation and then escaped Sydney aboard an American fur-trading vessel in early 1796. Muir eventually ended up in Paris, where he was feted before his life ended amidst illness and poverty in January 1799. Palmer had become a successful trader and shipowner and a friend to certain of the colony’s eminent, liberal-minded gentlemen. He died while en route to England in 1801. Despite being implicated in rumours of rebellion again during his first eighteen months in the colony, Mealmaker received a conditional pardon in 1803 and was thereafter supervisor of the weaving work conducted at the Parramatta Female Factory. Following the near destruction of the Factory in a fire in 1807, Mealmaker lapsed into impoverishment and alcoholism, dying as a result of ‘alcoholic suffocation’ in March 1808. Margarot outlived all of them, serving his time between Sydney, Norfolk Island, Van Diemen’s Land and Newcastle before returning home in 1810.

In 1837–38 A series of original portraits and caricature etchings by the late John Kay was published in two volumes with further editions appearing in 1842 and 1877. Providing an alternative record of Edinburgh in its golden age, Kay’s caricatures, hitherto considered unworthy of the notice of art history, now enrich the holdings of many a public gallery and prestigious collection, not the least being those of the National Portrait Galleries in Canberra, London, and – of course – Edinburgh.