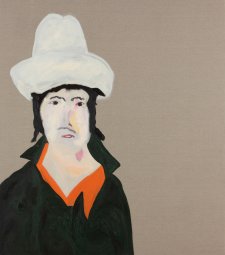

In 1932, Napier Waller painted his wife Christian on the lawns of their home in the outer-Melbourne suburb of Ivanhoe. Guarded by her three pet Airedales – Baldur, Undine and Siren – she looks out of the painting. Her expression has a Mona Lisa effect: one cannot be sure of the secrets behind her smile. Some see this as a portrait of a melancholy woman, comforted by her dogs, while others are struck by the intensity of her gaze, and the sheer scale of the painting.

Nothing was straightforward in the lives of Christian Waller née Yandell (1894–1954) and Mervyn ‘Napier’ Waller (1893–1972). Each from regional Victoria, the couple met when they were students at the National Gallery Art School in Melbourne in the years leading up to the First World War; they married in 1915. Nicholas Draffin, the late author of Napier’s monograph, wrote that the Wallers were drawn together by shared interests in folklore and mythology that had been advanced by British artists and writers during the Victorian Age, in particular by the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and the proponents of the British Arts and Crafts Movement. In their first two decades together, the Wallers produced bodies of work with strong parallels that engaged with the imaginative world; these can be seen in Christian’s watercolour Tristan and Isolde (c. 1925) and Napier’s print Hit (c. 1925). Napier’s experiences at war strengthened the couple’s disillusionment with modern life. In 1917, his right arm was amputated at the shoulder, the result of a wound he received whilst serving in Bullecourt, France. Miraculously, he taught himself to draw and paint with his left hand.

In the early 1920s, the couple moved into an Arts and Crafts home by the Darebin Creek, on a subdivided block of the Fairy Hills farming estate (surely the name is not a coincidence). Although the architectural plans were lost in a council fire several decades ago, Draffin and others speculated that Napier – and probably Christian – designed the home themselves, with guidance from an architect. It stills stands today, and lives on through the popular ABC TV series The Doctor Blake Mysteries; it is the location for the exterior shots of Dr Blake’s house. Certainly, sketches I have uncovered confirm their involvement in the design of furniture and garden beds.

In planning their intriguing house, the Wallers created an environment that espoused their medieval ideals; it had a minstrels gallery, hand-combed walls in the living room, custom made furniture designed and painted by Christian with characters from Arthurian legends, and an art studio (outdoor studios were added later). The house recalls William Morris’ Red House in England, designed by architect Philip Webb in 1859. Given the couple’s admiration for Morris and his circle, the house at Fairy Hills indicates a desire to embrace Arts and Crafts values in their personal life, as well as their art.

Napier’s portrait of his wife, entitled Christian Waller with Baldur, Undine and Siren at Fairy Hills, hung in pride of place above the fireplace in the living room. This large portrait was viewed by many influential figures who gathered at the Wallers’ home. Their good friend, the composer Fritz Hart, was a frequent guest, as were the artist Rupert Bunny and newspaper proprietor Theodore Fink, amongst other prominent Melburnians (even Robert Menzies is rumoured to have dined at Fairy Hills). One can only speculate as to what these visitors might have made of the curious home and the artist couple who shared it. Perhaps Napier, who was actively involved in the Melbourne art scene due to his role as a senior art teacher at the Working Men’s College (now RMIT University), was considered ‘one of the boys’, (he was, after all, a member of the Savage Club, an elite Melbourne gentleman’s club). Yet Christian, who was described by her niece, the ceramicist Klytie Pate (whom she raised from adolescence) as “a very interesting person”, must have seemed something of an enigma.

Never an artist who catered to the art market, Christian synthesised her aesthetic and spiritual values in her creative undertakings. This included her illustrations for some half a dozen children’s books in the 1920s, including Australian Fairy Tales (1925) by Hume Cook. Waller’s illustrations are not only marked by imaginative and symbolic expression, but suggest the interest in alternative spiritual philosophies that inspired her later work. As she matured, she became increasingly disinterested in the ‘real’ world, immersing herself instead, as Pate recalled in a 1992 interview, in theosophy and numerology. These arcane interests are expressed most powerfully in her exceptional hand-bound printed book, The Great Breath: A Book of Seven Designs, made in 1932, the same year as her husband’s portrait of her. The book, which features linocut prints imbued with arcane symbolism, was described by artist and critic George Bell as expressing “a metaphysical turn of thought”.

Napier Waller’s portrait of Christian captures her immersion in the spiritual realm. The symbolism of this portrait cannot be disregarded (her beloved Airedales were, after all, named after mythical figures). As she sits on the lawns of their home in her stylish Callot Sœurs dress, he shows her clutching a long beaded necklace in her left hand, with her right hand touching the pages of an open book; another book rests in front of her. Her pose is reminiscent of that of a religious saint; her necklace could easily be mistaken for rosary beads and her white dress conjures associations of divinity. Her pet Airedales are presented as her disciples; two stand at attention, while the other flops restlessly on the grass. In this way, the portrait highlights the spiritual path on which she had embarked. Indeed, Pate tells of people coming to her aunt for astrological readings and of the adolescents who would sit at her feet as she told stories of her travels to Ireland. Perhaps, during these occasions, she sat as she does in Napier’s painting of her?

In his insightful essay for the catalogue of the 1992 The Art of Christian Waller exhibition held at the Bendigo Art Gallery, art historian and curator Roger Butler proposed that Christian Waller’s linocut print, Morgan le Fay (c. 1927) is a self-portrait. So too, I would argue, is her 1916 painting, Destiny. In this work, Waller draws on her likeness for the sorceress, intently guarding her cauldron. Upon close inspection, the impressive detail of the painting reveals human beings trapped in the bubbles of the mysterious potion. Each of these images reveals much about the way Christian saw herself: as a formidable, spiritual woman.

Artists in love often use their art to express and explore their passion for, and frustration with, their significant other. In 2008, the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum in Cologne, Germany mounted a major exhibition Artist Couples: Love, Art, and Passion that explored the relationships between modern artist couples, with a focus on the ways in which their relationship shaped their art. What the exhibition revealed was that art is like a mirror; it reflects the experiences of its creator, including those at the most intimate levels.

Albert Tucker’s photograph In the mirror: self portrait with Joy Hester (1939), in the National Portrait Gallery’s collection, is one example in an Australian context. In the photograph, Tucker captures his and his future wife’s direct gaze in a mirror; the composition reinforces their shared romantic and artistic vision. This notion of a shared vision was also seen with the Wallers through their medieval idealism. Yet, like Tucker and Hester, and many other artist couples, they ultimately grew apart as they began to pursue different goals. This was the case in the Wallers’ lives as much as in their art.

In his portrait of his wife, Napier may have been articulating his emotional distance from his spouse by 1932, as Butler has discussed. It highlights her idiosyncratic nature and presents her as a woman of the spiritual, not the physical, world. Never formally separating, the couple experienced a significant rift in 1937. Napier began a relationship with one of his former students, Lorna Reyburn, as Christian became more immersed in her spiritual beliefs. In 1939–40 she travelled across America without Napier and spent time in New York, where she became a disciple of Father Divine, the leader of the International Peace Mission Movement. Upon her return to Australia in 1940, Christian assumed the role of spiritual emissary with greater vigour, and focused exclusively on making ecclesiastical stained glass windows to uplift and inspire the spirit.

In a 1948 interview published in Melbourne’s Argus newspaper, Christian stated that “work and God” were the two words printed on her mind, and declared her mission was to “get the message through… to make religion real”. There was no mention of her husband sharing this journey with her, and, judging by the themes of his art at the time, this was a solo mission. While Napier also produced ecclesiastical stained glass, this was part of a broader body of work that encompassed secular commissions.

In 1958, four years after Christian’s death, Napier married Reyburn, who had been working as his stained glass assistant for many years. The two lived out their lives at Fairy Hills. Following Napier’s wishes, the home is now preserved for posterity, managed by Heritage Victoria; it is listed on the Victorian Heritage Database as Napier Waller House.

After Christian died, Christian Waller with Baldur, Undine and Siren at Fairy Hills was given to Pate, who hung it in her home in the Melbourne suburb of Kew. In 1984, it was sold to the Australian National Gallery (now National Gallery of Australia), where it is on permanent display. There, Christian’s portrait intrigues and perplexes an ever-expanding list of onlookers to whom the subject is just as mysterious as it has always been.