John Singer Sargent was born in Florence, Italy, in 1856 to expatriate American parents, forever on the move across Europe. He trained as an art student in Paris, and it was there that he first came to public notice. During the 1890s, Sargent, American by citizenship but English by residence, became the pre-eminent transatlantic portraitist of his generation, painting many of the great figures of the age.

In 1886 he exchanged Paris for London, and his first professional visit to the US in 1887 resulted in a swathe of commissions and established his reputation. In 1890 he was given a commission for a major scheme of murals, Triumph of Religion, in the Boston Public Library, a project that would engross him for nearly thirty years. Anxious to complete his murals, and increasingly preoccupied with landscape painting, he gave up portrait painting (with rare exceptions) in 1907. Instead he offered his patrons portrait charcoals, of which he completed six hundred.

Sargent’s portraits are admired for their insight into character, for their sense of grand design, brilliance of light and colour and for their painterly fluency. The portraits that he painted of creative personalities are often a testament to friendship, but they also reflect the wide array of influences that formed his taste and aesthetic outlook.

Of formal education he had very little – he was largely taught by his father. The family moved with the seasons, from southern Europe to the Alps by way of Paris, Dresden and other northern cities. Along the way, Sargent acquired a wide knowledge of books, music, architecture and the fine arts. He was from the start a cosmopolitan, at home in Europe, where he spoke French, German and Italian as well as English. The life of leisure adopted by his parents was not one that Sargent wished to emulate. He was ambitious and eager to make a mark in the world, and from his early teens he had determined to be an artist.

The contemporary painter whom Sargent admired above all others was Édouard Manet, the great outsider. For years, Manet’s pictures suffered rejection and ridicule at the annual Salon, but he continued to exhibit works on a grand scale, and to the young artists of Sargent’s generation, he was a hero. At the Salon of 1882 the two most talked-of pictures were Sargent’s Spanish dance picture, El Jaleo, and Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère. While the first escaped the wrath of the critics for all its sketch-like handling, the second was generally condemned for its lack of narrative and meaning.

Sargent was regularly described in the press as Manet’s heir, but there is no record of them actually meeting, though they had several friends in common. With Claude Monet, Sargent led the campaign to purchase Manet’s picture of Olympia for the Louvre; he raised much of the money from his rich friends, while Monet squared officialdom. Sargent’s relations with the Impressionists are more problematic. He is said to have met Claude Monet in 1876 with French artist Paul Helleu, but this is uncorroborated. Monet was certainly a close friend by the mid-1880s and remained so throughout the 1900s. The high point of Monet’s influence on Sargent was in the period when Sargent was painting landscapes and figure scenes in the English countryside (1884–89). He not only looked on Monet as his mentor but also acquired no fewer than four of his landscape paintings. As a Salon portraitist, Sargent was regarded equivocally by members of the group: Camille Pissarro, whose London-bound sons were introduced to Sargent by the writer Octave Mirbeau, described him as very kind, ‘not an enthusiast but rather an adroit performer, and it is not for his painting that Mirbeau wanted you to meet him’. Mary Cassatt shared Pissarro’s view of Sargent, though Sargent was to paint her brother, the railway magnate Alexander Cassatt (whose portrait is in the Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission, Strasburg, Pennsylvania). Edgar Degas noted Sargent’s address in one of his notebooks but spoke disparagingly of him ‘as a skilful portrait painter who differed little from the better Salon painters then in fashion’.

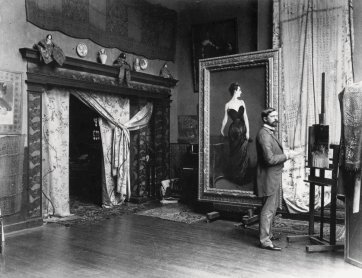

Sargent was never in any doubt that the Salon was the arena in which he had to succeed. Like Manet, he wanted success on his own terms, but his fall when it came was all the more galling because the work that provoked it, Madame X (Madame Pierre Gautreau), had been planned as a chef-d’oeuvre. Though a few critics spoke out in its defence, among them Judith Gautier and Henry Houssaye, the picture was roundly condemned as decadent and bizarre. It placed Sargent firmly in the camp of the avant-garde.

One of Sargent’s earliest patrons was the popular playwright Édouard Pailleron, whose father-in-law, François Buloz, was editor of the powerful and influential journal Revue des Deux Mondes. Pailleron commissioned portraits of himself; his wife Marie; and his two children, Édouard and Marie-Louise. The portraits of the Paillerons led to new patrons for Sargent. One of these was the wealthy and cultivated Chilean vice-consul in Paris, Ramón de Subercaseaux. The portrait of his beautiful wife, Amalia, seated at the piano, the epitome of Aesthetic elegance, won a second-class medal at the Salon of 1881. The Pailleron and Subercaseaux portraits may have been the spur for Dr Jean Pozzi to commission a superb and subversive full-length portrait of himself in 1881, dressed in oriental slippers and a bright red dressing gown. A distinguished gynaecologist, Pozzi embodied contemporary aesthetic values in his literary enthusiasms, his exquisite taste and his worship of the beautiful.

Sargent’s move to London in 1886 was not just an exchange of place and residence but also a profound shift in cultural landscape. He never entirely lost touch with Paris or the friends he had made there; its influence continued to shape his art and his taste. But over time, English culture, more conservative and provincial than in France, began to shape his outlook and ambitions. Through Vernon Lee, Sargent met Walter Pater, an Oxford academic; dined with Oscar Wilde, who had inscribed to him a book of poems by Rennell Rodd with the quotation: ‘To my friend John S. Sargent in deep admiration of his work. Oscar Wilde Paris April 5. Rien n’est vrai que le Beau’ [‘Nothing is true but beauty’]; visited the studio of the Pre-Raphaelite painter Edward Burne-Jones; enthused about the paintings of Dante Gabriel Rossetti and sat at the feet of the Pre-Raphaelite beauty and artist Marie Spartali (by then Mrs William Stillman).

Sargent’s enthusiasm for English Pre-Raphaelitism was a consequence of the aesthetic tastes he had developed in Paris. It found expression in his early English masterpiece Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose, where Aesthetic impulses – little girls dressed in white, lighting Japanese lanterns in a flower-filled garden – meet Impressionist principles of plein-air painting. The influence of Monet is strong at this period, as the friendship between the two artists deepened. Sargent visited Giverny around 1885 when he painted the well-known picture of Claude Monet, Painting, by the Edge of a Wood. He was there again in 1887, and Monet reciprocated with a visit to Sargent in 1888. Sargent’s comments, in a letter to a friend of 1885, that his work in England was thought ‘beastly French’ and that he might have to abandon art for business point to the downturn in his professional prospects. But he had fallen among friends, and the camaraderie of the Broadway colony, as well as the support of a few enlightened patrons, helped him through this difficult period. Broadway is a picturesque village, lying at the foot of the Cotswolds in the west of England, where two American artists, Francis David (‘Frank’) Millet and Edwin Austin Abbey, invited their friends to join them for summer breaks. The place was soon a hive of artistic and literary activity. Sargent was an enthusiastic early visitor, and while there he painted the wives of his artist friends (Mrs Frank Millet and Mrs Frederick Barnard). He also painted landscapes en plein air, as he was to do at Calcot and Fladbury later in the decade. Sargent’s picture, Robert Louis Stevenson and His Wife, of the same period, is a brilliant invention, a charged moment in the life of a great writer and personality.

A second professional visit to America in 1890 confirmed Sargent’s status as the favourite portraitist of wealthy Americans. Three famous American actors sat for him during that year: Edwin Booth, Joseph Jefferson and Lawrence Barrett; all three were portrait commissions for the recently founded Players Club in New York. They were preceded by the magnificent portrait of Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth, commissioned by Sir Henry Irving and displayed in the Lyceum Theatre in London. These portraits were followed by those of two great actresses, the American Ada Rehan and the Italian Eleonora Duse. This was the moment when Sargent’s involvement with the theatre was at its most intense.

The English took a little longer than the Americans to wake up to Sargent’s genius as a portraitist: Lady Agnew of Lochnaw and Mrs Hugh Hammersley shone above everything else on the walls of, respectively, London’s Royal Academy and New Gallery exhibitions of 1893. At the start of the 1890s, Sargent was associated with the New English Art Club, established in 1886 as an exhibiting society for progressive, mostly French-trained artists. The pictures he showed there were the daring, experimental landscapes he had painted in the English countryside. Whistler, of course, looms large in this period as the hero of the avant-garde. He and Sargent had met in Venice in 1880, and possibly earlier, and in 1886 Sargent took over his studio at 33 Tite Street, Chelsea, London. Whistler inscribed a later edition of his booklet, Whistler v. Ruskin: Art & Art Critics, ‘to John S. Sargent - with friendship and sympathy [butterfly signature].’ He also sent him the catalogue of his exhibition of Venetian etchings and dry points. Sargent on his part made every effort to involve Whistler in the mural projects at the Boston Public Library and urged Isabella Stewart Gardner to buy his famous Peacock Room (now in the Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC). Sargent’s surviving letters to Whistler suggest that the two men retained a guarded respect for one another and enjoyed cordial relations on a personal level only. The Royal Academy of Arts in London remained the focus of Sargent’s ambitions from the start of his residence in England, as the Paris Salon had been previously while he was living in France. It took the Academy seven years to overcome their objections to his radical funny-foreign style of painting and to admit him to their portals. Henceforth the Academy became the centre of his professional career, the place where he exhibited his most important works and where his reputation was forged. He was a loyal member of the institution, serving on committees and teaching in the schools. Sargent was followed into the Academy by younger, more progressive artists who changed its profile: Sargent’s friends from Broadway, Edwin Austin Abbey and Alfred Parsons, in 1894 and 1897, respectively; and two members of the New English Art Club, Frank Bramley and George Clausen, in 1894 and 1895.

Sargent’s contacts and networks extended beyond the confines of the British art world. He was associated with the international group of bravura painters that included the Italian Giovanni Boldini, the Swede Anders Zorn and the Spaniard Joaquín Sorolla. He continued to exhibit in Paris and to field French artist friends when they came to England. Monet, Helleu and Rodin all enjoyed his hospitality, assistance and support; he promoted their work in England and America and found them patrons among his rich and influential friends. It was Rodin who dubbed him the ‘Van Dyck of our times’ when viewing The Misses Hunter (now at Tate), at the Royal Academy exhibition of 1902. Sargent had introduced the sculptor to Mary Hunter, and a marble bust of her was the result (also at Tate). He also acted as the intermediary in negotiations between the sculptor and the art dealer Asher Wertheimer, but in the event no commission resulted.

Sargent was more revered in America than he was in England. He had many friends and patrons there, his work was regularly exhibited in American institutions, and by 1903 the first two phases of his mural scheme in the Boston Public Library had been installed and opened to public view. As his visits were few and far between (1876, 1887, 1890, 1895, 1903), his links with the American art world were necessarily circumscribed.

He remained in touch with older artists from his student days in Paris, among them James Carroll Beckwith, Augustus Saint-Gaudens and William Merritt Chase, the latter painted by him in an imposing presentation portrait of 1902. When asked in Philadelphia in 1903 if there were anyone he would like to meet, he named the painter Thomas Eakins, to the amazement of his friends. Eakins, now seen as one the pillars of the American school, was considered then in some quarters to be eccentric and morally unsound. Despite a heavy workload as a portraitist and muralist, Sargent lost none of his relish for other art forms. He was a frequent theatregoer, though details of what exactly he saw are lacking. He portrayed the handsome and talented Harley Granville-Barker in a sensitive charcoal drawing; he had some connection to the Irish theatre through WB Yeats and Lady Gregory, and he was present at a weekend party when he drew the actress Mrs Patrick Campbell peering over the shoulder of Gabriel Fauré. Not all was so high-minded, for Sargent is known to have had a penchant for Charlie Chaplin films and for music-hall reviews. In the field of music, Sargent continued to be enormously influential in promoting the careers of younger composers, among them Percy Grainger, Cyril Scott, Roger Quilter, Richard Strauss, Francis Korbay and Charles Martin Loeffler.

As Sargent’s career in formal portraiture waned in the 1900s, landscape painting waxed strong. Out of doors he was his own man, with no expectant patrons breathing down his neck. His landscapes and figure scenes painted out of doors became meditations on the nature of art as much as representations of things seen. The people who accompanied Sargent on his painting expeditions to the Continent, to the Alps, to Venice, to Rome, Majorca, Corfu and other parts of southern Europe, were fellow artists and friends, who shared his passion for plein-air painting and with whom he felt at ease. Sargent’s most familiar companions included his sister Emily, a talented watercolourist in her own right, and their faithful friend and recorder of their travels, Eliza Wedgwood; two artist couples, Wilfrid and Jane de Glehn, Adrian and Marianne Stokes; the painters Peter Harrison and Ambrogio Raffele from Vigevano in northern Italy. The latter features in one of Sargent’s most brilliant and enigmatic figure subjects, An Artist in His Studio. The bearded Raffele pops up in other Alpine scenes, for example in Reconnoitring, where, squatting on a stool, he assumes a monumental presence before a panorama of snow-capped mountains. The Great War ended Sargent’s sketching expeditions to Europe. He continued to paint out-of-doors on his travels in America and Canada, in the Rockies (1916) and in Florida (1917), and after the War along the coastline of Maine, but he never went back to Venice or the Alps or the Mediterranean. His last years were largely spent in Boston working on the mural commissions that he regarded as his most important artistic legacy. His bearded features and portly figure, those of a proper Edwardian, are captured in a photograph by the Boston photographer Henry Harper Pierce taken in the year before his death. He died in his sleep from a heart attack at his home, 31 Tite Street, in Chelsea, London, on the night of 12–13 April 1925, three days before his planned departure to Boston to install the last of his murals in the Museum of Fine Arts.

This extract of the essay ‘Sargent and the Arts’ from Sargent: Portraits of Artists and Friends is reproduced with the kind permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London.