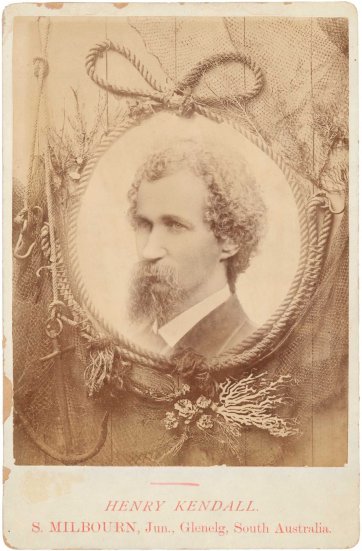

When the poet Henry Kendall died in the winter of 1882, aged just forty, journalist Francis J Donohue acknowledged that it was ‘pleasanter to review our poet’s works than his life.’ At that time, Kendall was lauded as the first poet to extol the colonies; he had even received a smidgin of patronising attention in England. Few twenty-first century Australians could name Henry Kendall; and pressed to give them a go, few could be induced to persevere with the perfumed verses of the ‘Australian Shelley’. From this distance, it’s certainly more interesting – if not pleasanter, exactly – to review his life than his works. His obituary in the Sydney Morning Herald sets the tone: ‘Mr Kendall’s career was chequered and gloomy, and overshadowed by great troubles, of which he may have been partly the victim, and partly the creator, but the few who gained an insight into his inner life knew that he often went out into the wilderness and wrestled terribly with his temper in a mental and physical struggle of which, happily, few know the terrors.’ Apart, perhaps, from the bit about the wilderness, exactly the same words could have been used about the life of Henry Lawson on the occasion of his death in Sydney fifty years later.

Henry Kendall, born in Ulladulla, lost his father at 13 and lived at his grandfather’s with his mother and siblings before spending two years on a whaling boat. When he returned at the age of 18, he had enough funds to enable his family to move to Newtown. He started submitting poems for publication while working as a law clerk in Grafton, and pressed on as he served as a clerk in the Department of Lands and the Colonial Office. By the early 1860s he had a volume of verse to his name and, at 29, he was in a position to marry 18-year-old Charlotte Rutter. Clerical work was an affront to his refined sensibility and his siblings were a drain on him, financially and reputationally; he moved to Melbourne. There, his reputation for poetry grew with the publication of Leaves from Australian Forests, but he returned to Sydney poor, sick and a drunkard. Just on four years after his marriage, he was consigned to the Gladesville Hospital for the Insane. At that time, as luck would have it, the facility was beginning to modernise, formulating treatment plans for patients rather than serving as a waystation on the road to a wretched death (it’s now estimated that 1,228 people were buried there in unmarked graves between 1838 and 1888). After four months, the gentle bard emerged, fostered by two brothers from Gosford and in due course working with a timber firm in that district. Surprisingly, by 1876 he’d recovered sufficiently for Charlotte and their children to return to him; he began to augment his income with pieces published in the Freeman’s Journal and, in 1880, his Songs from the Mountains was a success. The following year, Henry Parkes, the premier, but also a poet, tried to help Kendall further by making him New South Wales’s first Inspector of Forests – an exceptionally remunerative appointment. ‘When much that is ridiculous and impolitic on the part of the present Ministry shall be forgotten, this graceful recognition of genius will be recalled as an instance of a worthy and commendable public spirit,’ wrote Donohue. However, Kendall’s frail form was not equal to the forestry job, which involved punishing travel, and he died of phthisis (tuberculosis) in Bourke Street, Surry Hills, at forty. The village of Camden Haven, where he lived when he was happiest, was renamed Kendall in his honour.

Soon after Kendall’s death, public funds were collected for his wife and five children; later, they received a pension. In 1884, in an attempt to raise funds for a fitting memorial to the poet himself, politician Daniel O’Connor appealed to a Hungarian violinist, Edouard Remenyi, who was then performing in Sydney: ‘Two years ago the laureate of these lands, Australia’s best and sweetest singer, Henry Clarence Kendall, passed out of a troubled life, and, with a discreditable apathy and shameless indifference to his claim upon their eternal gratitude, his countrymen have up to this suffered his bones to lie unmarked, unhonoured, and unnoticed in the quiet cemetery at Waverley’, he wrote. Remenyi, gratified, prefaced his reply with some personal reflection: ‘Intercourse with lofty minds constitutes the real oasis of life for one thirsting after science and the beautiful. I am always thirsty.’ As Australians had treated him so well, he said (finally) that he would be pleased to mount a benefit concert when next in Sydney. O’Connor published his exchange with the foreigner to embarrass his own colleagues and countrymen into action, too. In 1886, Kendall’s remains were disinterred, and placed under a very substantial monument funded partly by a concert given by Remenyi at Sydney University. Evidently flushed with the success of this project, O’Connor orchestrated the re-burial of the alcoholic orator Daniel Deniehy at Waverley in 1888; that year, Remenyi dropped dead on the job in San Francisco’s Orpheus Theatre.

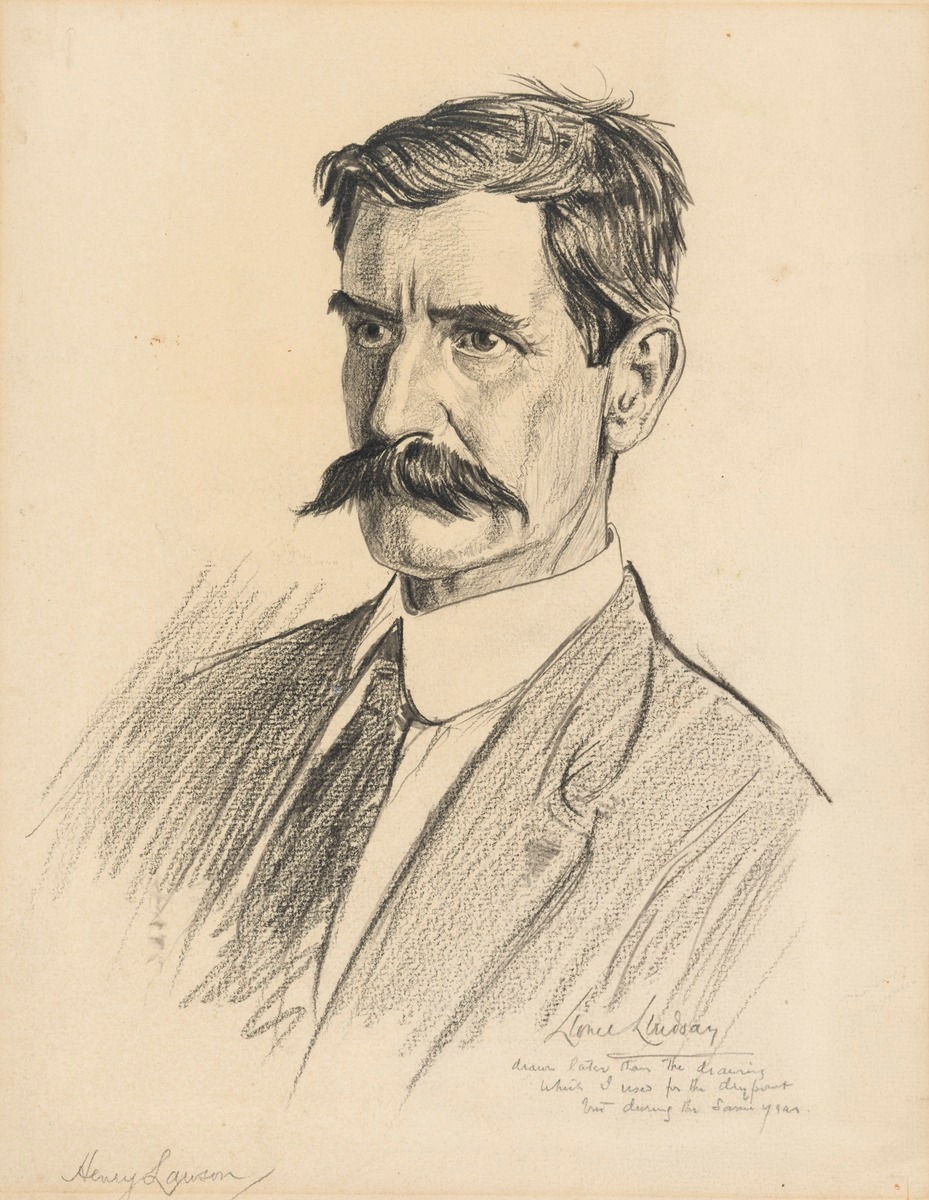

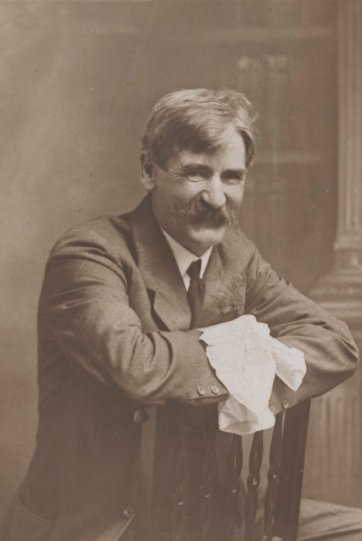

Henry Kendall was a pioneer interpreter of the Australian landscape; it was he who ‘lent articulate voice to the mute harmonies’ of its plants, rivers, rocks, dells and glades; the ‘dim mystery and eloquent silence, which had hitherto appealed mutely for expression, spoke first in his poetry, and reverberated in his song’. As late as 1926, when the Historic Memorials Committee decided that a national gallery of portraits would be established in Canberra, Kendall was amongst the five portrait subjects men proposed, along with WC Wentworth, Charles Sturt, Sir Thomas Mitchell and Sir Joseph Banks. Yet imagine a game-show question, now, beginning ‘Australia’s celebrated nineteenth-century writer is Henry … ?’ Almost any and every Australian adult would fire back with confidence: ‘Lawson!’ Some could even recite some facts about Henry Lawson’s life, or name one of his works. Many would recognise his face – or even, simply, his moustache – in a picture, though they would probably think that he lived earlier than he did, in the bush, without electricity or other infrastructure; his renowned stories describe life in the hazy era of those pictures by Tom Roberts, Arthur Streeton and Frederick McCubbin that used to be reproduced on the walls of country motel rooms. Lawson, in fact, was exposed to the latest in modern living in New Zealand and London, where many would be surprised to know he spent some years before 1903; and, of course, he saw the machinery of capitalism grinding in Sydney – the downtrodden and itinerant inhabitants of which he wrote about, too. Lawson wrote through a time of profound change in the social fabric of New South Wales. In an outstanding example of his urban stories, ‘Going Blind’, the narrator tells of his encounter with a bushman who ‘seemed as if he had forgotten to grow old and die out with [the] old colonial school to which he belonged.’ Like many of Lawson’s stories, ‘Going Blind’ begins in confidently unadorned style: ‘I met him in the Full-and-Plenty Dining Rooms.’

Henry Lawson, born in a goldfields tent in 1867, spent his childhood on a poor selection in the Mudgee district in New South Wales. During his brief schooling at Eurunderee, he lost most of his hearing; an other-worldly child of delicate appearance, he was bullied. His mother, a girl from Guntawang who became a quarrelsome, disillusioned wife and apparently a fairly neglectful parent, nevertheless encouraged him to read widely while she dragged herself up by her own bootstraps. In 1884 she left Henry’s father, a commonsensical teetotaller who shrank from unpleasantness in the home, and moved to Sydney, where in 1888 she founded the women’s newspaper The Dawn. Before she left, Henry had been working with his father as a carpenter and painter, but he moved to Sydney before stints in Newcastle and Melbourne, the Blue Mountains, Western Australia and Brisbane. Though he came to hate the women in his mother’s circle – especially Rose Scott, who viewed him squarely from the perspective of what he would be like for a woman and children to live with – he was strongly influenced by Louisa, and took a nationalist, egalitarian and pro-union stance that made him a natural contributor to the Bulletin in the 1890s. Fatefully, in 1892, the journal’s proprietor, Jules Archibald, gave him a train ticket to Bourke and a five-pound note. Arriving in Bourke in January 1893, he walked to Hungerford on the Queensland border; later, he walked back to Bourke. He was away for about six months. This experience, combined with his early life on the diggings, informed scores of stories and vignettes that were to be collected in evocatively-titled volumes including In the Days When the World Was Wide, While the Billy Boils, On the Track, Over the Sliprails and Joe Wilson and His Mates.

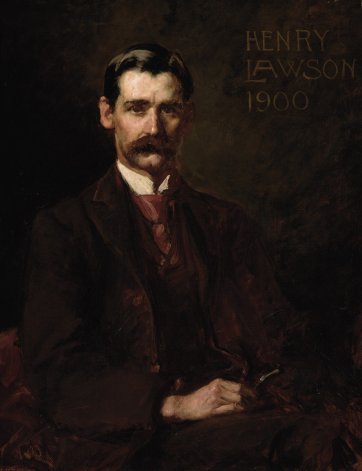

Lawson’s mother published his first book in 1894; he married Bertha Bredt, and had two books published, in 1896; he was first hospitalised for alcoholism in 1898. Having ‘got straight’, he was painted by John Longstaff in Melbourne on the way to London with his wife and their two children. Manning Clark wrote that he saw the painting only once outside the studio; never again could he face it, Clark wrote, ‘because of the tragedy of his life which began in that year’. That said, in Lawson’s tragic years, he was to sit for many more portraits.

London crushed Lawson – as it did several other Australian expatriates of the period. Bertha Lawson was hospitalised there, and after two years in the city the blighted pair set out for Sydney in separate ships. She left him in fear of violence; stupefied by alcohol, he toppled over a cliff at Manly at the end of 1902. At thirty-five, his best work was over. Thenceforth, subject to catastrophic bouts of depression and alcoholism, Lawson shambled around Sydney, sometimes confined to Darlinghurst Gaol or its mental annexe, sometimes nurtured by a kind admirer, Isabel Byers, failing to pay family support, growing more bitter and more paranoid, still writing but detracting from his reputation with every word. In 1915 he and Mrs Byers moved to Leeton, where alcohol was supposedly unavailable; but he got some, and then he got some more. After publishing a poem supporting conscription he was repudiated by the Labor movement. Pained by his terrible decline, friends again tried to send him to sanctuary in the country near Gundagai, but he returned to Sydney in the January heat of 1920 and was back in the Darlinghurst mental hospital by the winter that year. While he was there, his mother died in the Gladesville Hospital for the Insane. In the wake of a cerebral haemorrhage the following year, he had all his teeth removed. Having staggered around his old haunts for a few months more, a ghastlier ghost than ever, he was found dead, clad in just a singlet, in the back yard of a house in Abbotsford on the morning of 2 September 1922.

Henry Kendall’s poems pulsate with descriptions of Australia’s trees, flowers and creeks, the relief they offer from its cities and the rueful memories of happier times they evoke. A snatch from ‘Araluen’ – commemorating Kendall’s dead daughter – is, well, not atypical:

River, myrtle-rimmed, and set

Deep amongst unfooted dells –

Daughter of grey hills of wet,

Born by mossed and yellow wells;

Now that soft September lays

Tender hands on thee and thine,

Let me think of blue-eyed days,

Star-like flowers and leaves of shine!

Cities soil the life with rust;

Water banks are cool and sweet;

River, tired of noise and dust,

Here I come to rest my feet.

The poet’s feelings are inseparable from the language in which he evokes the natural world; we feel his emotions running in its river, sucked up by its moss and vulnerably exposed in its flowers. By contrast, Henry Lawson’s prose ‘sketches’ and stories introduce the landscape like elements of stark stage sets, on which actors’ exchanges take place. So, the first paragraph of ‘Our Pipes’ reads:

The moon rose away out on the edge of a smoky plain, seen through a sort of tunnel or arch in the fringe of mulga behind which we were camped – Jack Mitchell and I. The ‘timber’ proper was just behind us, very thick and very dark. The moon looked like a big new copper boiler set on edge on the horizon of the plain, with the top turned towards us and a lot of old rags and straw burning inside.

The rest of the 4-page piece comprises description of the men’s preparations for camp, and their after-dinner dialogue; it ends with a soft question, and a sad response, underplayed.

The hectic brilliance of ‘The Loaded Dog’ notwithstanding, that farcical yarn of bumpkins’ shenanigans is unusual in Lawson’s body of work. Anyone assuming that the author merits credit or blame for ratifying such clichés of Australian identity as the nobility of the bushman and the primacy of mateship might well take a fresh look at the stories, which simultaneously honour and call into question the sincerity of relationships between men. Frequently, they comprise sketches of awkwardness, frustration and fragile moments of empathy between people unfitted, from childhood, to talk over a matter from a variety of perspectives; now, the very terseness of the stories makes for their impact. Many of Lawson’s sparely-delineated images, such as this in ‘The Drover’s Wife’ might lodge in the imagination for a lifetime:

All days are much the same to her; but on Sunday afternoon she dresses herself, tidies the children, smartens up baby, and goes for a lonely walk along the bush-track, pushing an old perambulator in front of her. She takes as much care to make herself and the children look smart as she would if she were going to do the block in the city. There is nothing to see, however, and not a soul to meet.

Lawson strikes a clean blow at cliché (and adjectives) in one of his great elliptical stories, “The Union Buries its Dead”, describing the internment of a young stranger, unknown to every man who accompanies his coffin through the glare to the grave:

I have left out the wattle – because it wasn’t there. I have also neglected to mention the heart-broken old mate, with his grizzled head bowed and great pearly drops streaming down his rugged cheeks. He was absent – he was probably “Out Back”. For similar reasons I have omitted reference to the suspicious moisture in the eyes of a bearded bush ruffian named Bill. Bill failed to turn up; and the only moisture was that which was induced by the heat. I have left out the “sad Australian sunset” because the sun was not going down at the time. The burial took place exactly at mid-day.

Another story of a funeral, ‘The Bush Undertaker’, gestures persistently at the uncanny, although all its spookiness is rationally explained. A bushman struggles with two dead bodies on a hot Christmas day. One, an Indigenous person’s, he hunts out and exhumes, placing the bones in a bag. The other, his old friend Brummy’s, he finds sitting under a sapling, as dry as a mummy. Wrapping the carcass in bark, he carries Brummy home, drinking rum from the dead man’s flask, grappling with the bag of bones and shadowed by a ‘great greasy black goanna’ that he believes to be several different reptiles – comprising a strange flock.

Although ‘used to the weird and dismal’, during the night in the slab-and-bark hut he and his dog Five Bob fear the noises they hear. It transpires that it’s the ‘gohanner’. Towards daybreak, he shoots the beast, and observes its violent convulsions on the ground, shouting that the ‘cuss-o-God wretch has a-follered me ‘ome, an’ has been a-havin’ its Christmas dinner of of Brummy, and a-hauntin o’ me into the bargain, the jumpt-up tinker!’ Determined to give Brummy a comfortable burial, he digs a hole and drops his stiff corpse into one corner like a post before settling him in. Then, with a solemnity that unsettles Five Bob, he intones ‘Hashes ter hashes, dus ter dus, Brummy – an’ – an’ in hopes of a great an’ gerlorious rassaraction!’

Lawson’s own funeral could not have been more different. A state affair, held in St Andrew’s Cathedral, it was attended by hundreds of mourners including both Billy Hughes and Stanley Bruce; the crowd on George Street was such that those in the church found it difficult to leave, and people lined the route from the city through Paddington and Bondi Junction to Waverley Cemetery. There, oddly enough, the poet’s skinny 55-year-old body was buried in the grave initially occupied by Kendall. Lawson’s accommodation has never been upgraded. In 1920 there were reports in the Herald of a movement to erect a statue of Kendall in the Domain. That plan came to naught; in Sydney, Kendall is commemorated in a bench in the Botanic Gardens. Though it virtually killed its procrastinating, harried sculptor, George Lambert, it’s Henry Lawson whose statue stands in the Domain.