Most people know – and love – Alan Marshall for his childhood memoir I can jump puddles (1955), but certainly for adults, These are my people (1944) is the most boldly authentic interpretation of the many voices Marshall captured for us in his books and stories over his eighty-two years.

These are my people is essentially a travelogue of Marshall and his wife’s travels around Victoria during the Second World War. Marshall set out to listen and recount the stories of those who stayed behind. Marshall was one of those who stayed behind; due to his disability – polio in childhood – he was scarcely mobile, even with the use of crutches. There are eleven editions of the original 1944 publication of These are my people, wrapped in admiration and attribution of the artists and writers of the day. For example, in 1957 there was an edition with a foreword by Vance Palmer and illustrated by Ron Edwards, and there is a sturdy, workaday 1984 edition which included a series of dark lithographs by Rick Amor.

Just as in I can jump puddles, Marshall’s descriptions in These are my people of living with his ‘brummy legs’ as he travels for miles and for months in a horse-drawn caravan, is wry, never sorrowful, but more than matter of fact. His anecdote of searching for the horses after they’ve wandered off in a morning of penetrating cold rain, crutches slipping in the mud, ripping the skin of his numb legs, brings some understanding to the reader of Marshall’s stoicism and acceptance. Similarly, in I can jump puddles, his description of months spent in a hospital for rehabilitation, at about ten years of age, in the early years of the twentieth century will stay with the reader forever; the intuitive and sunny child is experiencing horrific pain and homesickness, and yet he is most occupied with the wish to cheer his fellow (adult) patients.

In his early adult life, Marshall lived and worked with the ‘ratbags’ of Melbourne; the left, the socialists, the communists – groups of people, often workers, who dreamed of a more equal paradise. He wrote for Worker’s Voice, the Communist Review and the Left Review; Smith’s Weekly, the Bulletin, ABC Weekly, Bohemia and Meanjin. He edited the anti-fascist review, Point, and was president of the Victorian Writers’ League; though he never joined the Communist Party, he attracted the interest of ASIO immediately upon its formation in 1949. His writing was rarely overtly political, but glorified honesty, earthiness, labour, charity, authenticity and simplicity. For many of his adult years he lived and worked in Eltham, and became one of the influences for the fertile period in that halcyon location.

Steven Murray Smith describes Marshall in the introduction to The Complete Stories: ‘[He] not only holds a firm place in the thoughts of all who have known him ... but is a man who is regarded with national affection. This was partly because his art was never pretentious. He never tried to be trendy: on the other hand he was never self-consciously folksy either. Of course he has been punished for this, as Lawson was too, for two generations.’

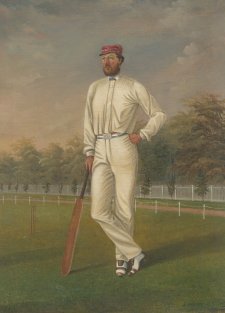

Robert Sessions was the publisher at Nelson at the time of The Complete Stories publication. Sessions has fond memories of conversations with Marshall in the preparation of the book: ‘He seemed bemused, as though no-one would be interested in his stories.’ The decision was to produce a hardback, a paperback and a limited, slip case edition of 500 all at the same time, with all three using the stunning portrait as the key art; ‘it was what publishing did in those days,’ says Sessions.

He recalls the use of the Noel Counihan portrait of Marshall as a cover was Alan’s idea. Sessions says, ‘I can hear Alan’s voice, in that funny kind of gruff way … Alan put us onto it and we knew instantly it was the right thing.’ Counihan also did ten drawings for The Complete Stories of Alan Marshall, including one that was for use only in the limited edition, tipped in as a frontispiece, with the plate then destroyed.

Marshall and Counihan had been friends for some years before the portrait was done. They seem to have known each other through family and friends before they found themselves in Swan Hill, Victoria, in 1970. Counihan had been there before and introduced Marshall to his local friend, Jenny Hadlow. For an outing, Hadlow drove them a short way to Goodnight, NSW, and there took Counihan and Marshall for a walk on the banks of the Murray River, under the famous River Red gums. The three experienced a significant few hours, where the natural surroundings brought about a kind of profound insight.

‘No tree can equal the River Red gum. The old red gums of the Murray are infinitely wise, a wisdom they can communicate to those who rest their hand upon them,’ Marshall wrote later.

That night Marshall was his garrulous and personable self, enthralling the group with his wit and storytelling. During the evening, Counihan saw that Marshall was full of a lively humanity, and madly sketched him; he seemed inspired by the place, the river, the people. Jenny quietly asked Counihan what he would do with the sketches; he said he wasn’t sure, he hoped it would lead to a portrait, but he’d ‘never got him’ (Marshall) before.

Weeks later Counihan wrote to Hadlow to thank her for their visit and enclosed a photograph of Hadlow and Marshall at that spot by the river, Marshall dressed in the distinctive red jumper that was soon seen in the portrait. Counihan wrote ‘I feel rather happy about a small portrait I am painting of Alan (he doesn’t know anything about it!). It’s rather fresh and sunny.’

Counihan sold the portrait to the Hadlows in 1971, and for almost all the years since, it has hung in the family home, much loved, a talisman of the friendship and admiration between the artist, the subject and the family, until its donation to the National Portrait Gallery in March 2015.

Counihan is not especially known for his portraits; indeed this is the first of his works to be included in the Portrait Gallery’s collection. There is his harsh, memorable 1983 Self-Portrait at 70 in graphite, and, held at the National Gallery of Victoria, another Self-Portrait, 1973 in oil, and one of Judah Waten. There is one of Vance Palmer at the National Library, and one of Katherine Susannah Prichard held at the National Gallery of Australia. He executed some commissions in the late 70s and early 80s, most of which are held privately.

Counihan, born in Melbourne, began his career as a press caricaturist, freelancing in Australia, New Zealand and Europe in the 1930s and 1940s. In the early 1950s, between four and six-year stints as a staff artist for the Melbourne Guardian, he worked for the World Trade Union Movement in London. In Melbourne, throughout the 1950s and 1960s, he exhibited pictures of miners, construction workers, demonstrations and other scenes of working-class life.

Between 1951 and 1960, his work was shown in London, Warsaw, Copenhagen, Moscow and Leningrad; during this period he won the Crouch Prize twice, the McCaughey Prize and the VS drawing prize as well as a bronze medal at the International Graphics exhibition in Leipzig.

In 1969, he exhibited in Poland and the USSR. The NGV held a survey of his work in 1973, in which year he also had a survey show at the Commonwealth Gallery in London; Marshall’s portrait was included in both. In 1974, he had a residency at the Cité in Paris. In 1982, he lived in France, based in the village of Opoul, southwest of Paris, and produced a body of work depicting French village life.

Marshall says of portraiture and the Counihan portrait in particular: ‘I like it ... one changes with the years, the face becomes shorn of irrelevancies, the lines deepen, the structure of the face becomes more prominent and the bare man looks out on the world. This is what Noel has captured. I think it is a masterpiece.’