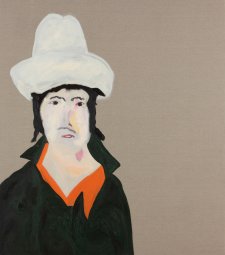

Arthur Boyd was in his mid-20s when he painted this vivid, thoughtful self portrait.

Although conscripted into the army during World War II, leaving him with relatively little time to paint, Boyd found his artistic voice during those years. Those early pictures spoke urgently and forcefully about the fallen state of man. Gargoyles on the roofs of a South Melbourne street could spring to life and terrorise a crippled man. Lovers outstretched in an orchard reflected more agony than ecstasy. Boyd's vision of the Australian landscape was equally grim. The bush took on a primeval quality, sunless and sullen, inhabited by anonymous hunters more lost than purposeful. Boyd, along with his friends and fellow artists Sidney Nolan, Albert Tucker, Joy Hester and John Perceval, felt oppressed by the war. All save Hester and Perceval were conscripted, but none saw any action. Boyd was assigned to the Cartographic Unit and never got closer to the front than Bendigo.

This self portrait catches Boyd awakening from that long oppression, looking cautiously ahead to see what peace might bring. The war and its aftermath were deeply unsettling times. Rarely before in Australian art had a generation produced such a succession of self portraits as Nolan, Tucker, Boyd, Hester and Perceval did during the 1940s. All of them have a self-questioning quality. All of them would have known the famous lines by Stephen Spender, then a much admired British poet:

Who live under the shadow of a war,

What can I do that matters?

Each artist found an answer to that question in their work. Nolan would start his first Ned Kelly series in 1946. Tucker became ever more deeply engrossed in his Images of Modern Evil series. Boyd, who stands on the cusp of his early career in this self portrait, would launch into his first major biblical series. The Expulsion from Eden would be re-enacted amongst the scruffy ti-tree of the Mornington Peninsula. The Money Changers would be thrown out of a suburban church.

The landscape of the Mornington Peninsula had a profound and personal importance for Arthur Boyd. Unhappy at school, he left when he was 14 and, with a difficult and financially stressed family background, Boyd escaped to the Mornington Peninsula at the age of 16 to live with his grandfather, Arthur Merric Boyd, also a fine painter. The young Boyd began to paint the landscape and the seashore under the gentle tutelage of his grandfather. These early landscapes had a precocious brilliance.

Van Gogh was an early guide and source of inspiration. Boyd took from him the lesson of painting directly from the landscape, in colour. The Dutch master’s celebrated self portraits equally affected the young artist. Between the ages of 15 and 18, Boyd painted a group of self portraits, at times painfully truthful. The most accomplished and best known of these early explorations of the self is Self-Portrait in a Red Shirt 1937 (National Gallery of Australia). Painted when he was 17, it looks forward strikingly to the later Portrait Gallery self portrait. The red shirt in the 1940s designated, in a loose and generalized way, a rebellious and revolutionary spirit. How subtly the mood changes from the defiant yet vulnerable stare of the 17 year old to the averted, self-questioning gaze of the 1945-6 self portrait. The chiaroscuro that plays so sensitively over Boyd’s face in the later work shows a marked expansion of method and approach, compared to the bluntness of the earlier work. The defiant youth has become the perplexed young man.

Between these two self portraits lies another disguised self portrait. In 1938, Boyd painted himself and his two brothers, Guy, a sculptor and ceramicist, and David, potter and painter, in a dark and swirling expressionist manner. Titled Three Heads, Boyd added in brackets (The Brothers Karamazov). Dostoevsky was widely read in the 1940s by Melbourne artists and writers. Boyd's affinity for the Russian’s ultimate novel, with its internalized struggle between good and evil, (“God and the Devil are fighting and the battlefield is the heart of Man”) ran deep and lastingly. Dostoevsky opened up to Boyd a sense of the tragic in the human condition. The brother with whom Arthur Boyd most clearly identified was the dreamer, Alyosha. In Book I, Dostoevsky introduces Alyosha as follows:

In his childhood and youth, he was by no means expansive, or talked little indeed, but not from shyness or a sullen unsociability, quite the contrary, from something different, from a sort of inner preoccupation, entirely personal … But he was fond of people, he seemed throughout his life to put an implicit trust in people … he did not care to be a judge of others that he never took it upon himself to criticize and would never condemn anyone…

Anyone who knew Arthur Boyd (or even knew about him) would see how closely this description fits the artist. It is not too fanciful, I hope, to see the National Portrait Gallery’s fine and moving self portrait as a portrait of the artist as Alyosha Karamazov, a man seeking and emerging into light.