George Seddon AM (1927-2007) covered such a remarkable range of disciplines in his life that before he died he was dubbed ‘The Professor of Everything’.

Born in Berriwillock, Victoria, he studied English at Melbourne University before spending several years abroad, travelling and teaching at universities in Europe and North America. He returned to Australia in 1956 to take up a lectureship in English at the University of Western Australia. He completed a bachelor’s degree in science in Perth, with a major in geology, before returning to the USA, where he obtained master’s and doctoral degrees in science from the University of Minnesota. He briefly repatriated before taking up a professorship in geology and geophysics at the University of Oregon. In 1970, he published his first book, Swan River Landscapes.

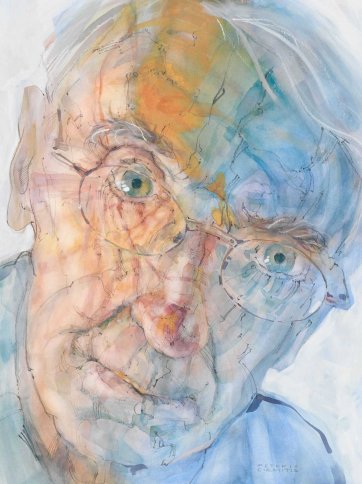

During the 1970s Peteris Ciemitis, son of Latvian refugees, was studying planning and urban design at the West Australian Institute of Technology, not knowing that he would later study art at Perth’s Claremont School and enjoy parallel careers in planning and painting. For planners and designers of Ciemitis’s generation, Seddon’s 1972 book A Sense of Place was essential reading. The artist recalls poring over the work ‘relentlessly’; ‘it became a cornerstone of my own philosophy and relationship to country and the people within it’.

From 1971 to 1974, Seddon was chair of the History and Philosophy of Science program at the University of NSW. Having been the founding professor of Environmental Studies at the University of Melbourne in the second half of the 1970s, he was dean of its Faculty of Architecture and Planning from 1982 until 1987. In Melbourne he wrote Your vegetable garden in Australia (1983) and A city and its setting (1986).

In his article ‘The evolution of perceptual attitudes’ in Man and landscape in Australia: towards an ecological vision (1976), Seddon describes how as child growing up in the Wimmera, he was surrounded by wheat, introduced eucalypt species, and the ‘limited range of exotics common to country town parks and gardens’. The only animals with which he was familiar were the stuff of plastic farmyard playsets: dogs, cats, rabbits, horses, sheep and cows. There were birds, but he knew little of them, other than the magpie, and the sparrows, starlings and mynahs that gathered around the house. ‘I could have explored nearpristine bushland in the Grampians, and we did sometimes “go for a drive”… but it was not my day to day environment’, he writes. ‘I had to learn to begin to see Australia… I think my experience is typical, and it is not therefore surprising that we have amongst the lowest standards of environmental design in the world… The imaginative apprehension of a continent is as much a pioneering exercise as breaking the clod.’

A bonus of Seddon’s multiple specialisations is that amongst his twenty-eight books and innumerable essays and papers, there’s something for everybody. Seddon’s essays on gardens – whether his account of the changing function of ‘The Australian backyard’, or ‘Gardening across Australia’, an account of the very different gardens he created in his own homes in Claremont, Paddington, Hawthorn, Richmond and Fremantle (where he retired) – are full of pleasures. The gardens he created express stages on his physical journey around the continent, and his personal evolution.

‘In one’s own garden, one is in contact with the whole globe, both cognitively and imaginatively’, he suggests. Seddon’s writing has often been commended for readability (a legacy, no doubt, of his original academic specialisation; late in life, too, he returned to read Australian literature at the University of Western Australia). Searching for the Snowy: an environmental history (1994), won the Eureka Prize for science writing; not long after he was awarded the Mawson Medal of the Academy of Science for his contributions to geology.

A serendipitous introduction to Seddon thirty years after his decisive shaping of

Ciemitis’s way of seeing the world ‘closed a circle’ for the artist. Ciemitis in painting his portrait of Seddon aimed to capture a sense of his subject’s connection to the Australian landscape. As he sees it, it is ‘not only a map of George but a reference to a map of place: the environment with which George is concerned’. By his own account, the close perspective allowed him ‘to dispense with the inclusion of literal context’, and instead allowed him to use layers, light, flow and patterning around and across the face to convey his personal response to his sitter.(Employing a similar idiom, he won the Black Swan Prize for Portraiture in 2010 with a portrait of Robyn Archer.) His close cropping of the portrait freed him to ‘abstract’ aspects of it, but he writes that ‘the fixed gaze and the unnerving proximity were deliberate devices used to convey my sense of George’s incisive intellect and focus.’ The artist recalls the many hours that he sat with Seddon at his cottage in Fremantle, drawing and painting from close talking distance. To establish his composition and adjust for perspective, he relied on photographs from the session, which they finished ‘lens to nose’ with Seddon participating playfully in the process. In hindsight, Ciemitis is grateful that his introduction to Seddon enabled him to offer a parting gift of sorts; a record of his memory made shortly before he died.