Vanity Fair is considered the most successful society magazine in the history of English journalism. The weekly publication, which ran for nearly fifty years from 1868 to 1914, was the product of the unique vision of its founder and editor, Thomas Gibson Bowles (1842-1922).

Publishing political, social and literary pieces, the magazine invited readers to recognise the vanities of Victorian society. In essence, Vanity Fair treated the world of wit and fashion to a clever and amusing show of political and social ‘vanities’. So successful was this model that the publication soon became emulated by other society magazines.

The truths that Vanity Fair boldly revealed were suitably accompanied by caricatures which were often the most interesting and popular feature of the magazine. Indeed although the British version of Vanity Fair is no more, its caricatures remain as witty and entertaining as ever. It is therefore fortunate that the National Portrait Gallery holds a small yet fine assortment of these of original chromo-lithographic prints on paper. The collection features an array of English and Australian subjects including politicians, sportsmen, an artist and an author. However they are all united as ‘builders of the Empire’. Consequently, the caricatures act as colourful records of some of the prominent figures in our Nation’s early history.

Before Vanity Fair, the combination of caricature and colour lithography had never before been attempted in England. In fact the few early attempts to use the medium for graphic humour failed to compete with wood engraving as the popular means of reproduction. By the time the first Vanity Fair caricature was published (an illustration of Benjamin Disraeli by Carlo Pellegrini, also known as 'APE' or 'Singe', in 1869), the relatively and new and expensive technique of chromo-lithography had only begun to be exploited by the periodic press. In harnessing the expressive power of caricature, the Vanity Fair illustrators were no doubt inspired by the lithographed portrait chargé introduced by Honoré Daumier in 1830. By the 1860s, this mode of social satire and ridicule had gained ascendancy in France and Italy. However, it was the Neapolitan version (a more good-humoured take on the ferocity of French satire) that Carlo Pellegrini introduced to Vanity Fair and which became the accepted model for later cartoons.

Of the Gallery’s set of thirty-two chromolithographs, eighteen are by Sir Leslie Ward. Ward was introduced to the magazine in 1873 after a series of new cartoonists had failed to live up to the wit and artistry of Pellegrini and James Jacques Tissot (also known as 'Coïdé'). Ward was the ideal candidate, as at the age of twenty-two he had not only been groomed for society but had also trained himself to mimic 'APE' to perfection. From then on, Ward became the loyal 'SPY' whose permanent association with Vanity Fair made its weekly caricatures a national institution.

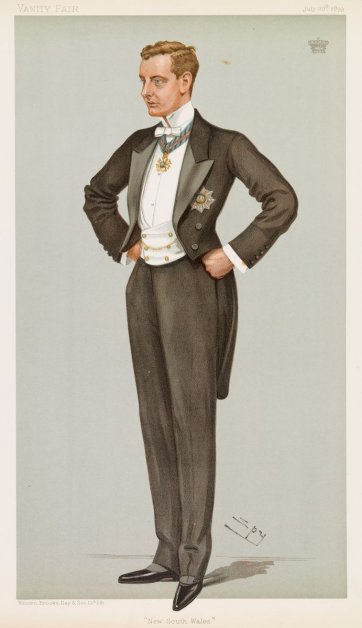

Although the caricatures in the Gallery’s collection originate from a British magazine, they strongly resonate with an Australian audience due to their illustration of several historic (and notorious) figures of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Ward’s caricature of William Lygon, seventh Earl Beauchamp, affords the viewer a visual representation of one of Ward’s most intriguing subjects. Beauchamp was a politician and Governor of New South Wales from 1899 to 1901. It was during his first year as Governor that Ward caricatured him, labelling his image 'New South Wales'.

At times, Ward was overly sympathetic to his subjects, thus this image of a sombre yet elegant Governor is little more than a very mild attempt at satire. However, its unassuming appearance belies the scandal which shadowed Beauchamp’s life. The two years of his governorship were beset by a number

of amusing gaffes. His arrival in the Colony in May 1899 was unforgettably preceded by the publication of a message, adapted from Kipling: ‘Greeting! Your birthstain have you turned to good.’ Then, at Cobar in September of that year he offended French colonists by condemning the Dreyfus trial and expressing pride in being an Englishman rather than a Frenchman. As he wielded little influence in an increasingly radical and nationalist political landscape, Beauchamp was an unsuccessful Governor and abandoned the colony in 1900. Thus he is perhaps more renowned for the life he led after returning to England. On 26 July 1902 Beauchamp married Lady Lettice Mary Elizabeth Grosvenor, daughter of Earl Grosvenor, eldest son of the 1st Duke of Westminster. He further enjoyed an increasingly powerful position in the British Parliament. Then, in 1931, he was threatened with divorce and the criminal proceedings that would reveal his homosexuality (including details of a particularly scandalous romp with his valet during a trip to Australia in 1930). In response to this, Beauchamp resigned from all of his appointments, except the lord wardenship of the Cinque Ports and went into exile in 1931. Such a history demonstrates the value of these caricatures to act as tangible mementos of people long gone.

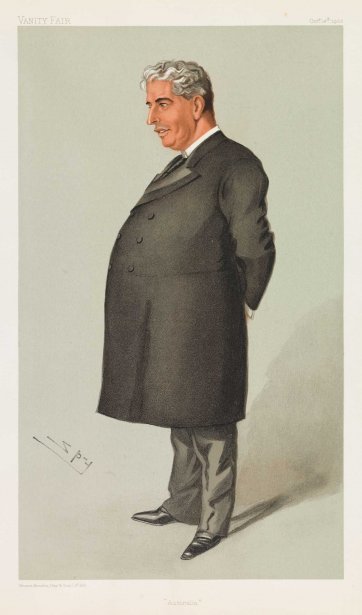

While Ward caricatured other historically important figures, two are particularly significant. The cartoons of Sir Edmund Barton and Alfred Deakin illustrate two figures that were instrumental in forming our early government. Ward’s caricature of Sir Edmund Barton was published in 1902, the second year of his term as Australia’s first Prime Minister. In the caricature Barton’s portly figure is clearly recognisable beneath his black frock coat and his shock of white hair is also prominently displayed. The title, “Australia”, alludes to his synonymy with Australian politics, as does the representation of another of Ward’s ‘victims’ – Alfred Deakin. As with Barton’s caricature, Deakin’s is similarly tied to Australian politics due to the title they share, “Australia”. Made in 1908, the latter portrait commemorates Deakin’s rise to prominence as Australia’s second Prime Minister– taking over when Barton retired to the High Court in September 1903 – and his resignation on 13 November 1908. The work is arguably more sycophantic than satirical, but it gives contemporary audiences an insight into his imposing stature and powerful gesticulation. Moreover the amusing quality of these caricatures is a welcome change from the stuffy representations generally afforded to political figures of this era.

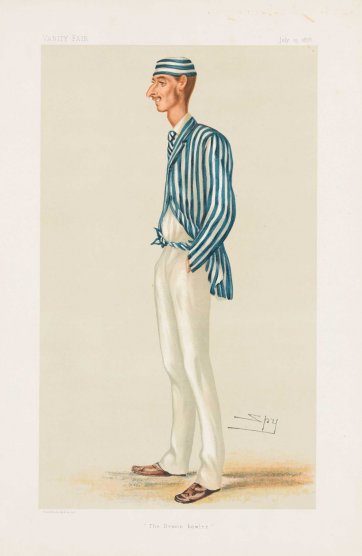

Although England’s white dominions were more sparsely treated in Vanity Fair than other parts of the Empire, one last caricature evinces the efficacy of the illustrations to commemorate notable Australian figures. Frederick R Spofforth, 'the Demon Bowler', was arguably the Australian cricket team’s finest pace bowler of the nineteenth century and the first bowler to take fifty Test wickets. He was also the first to take a Test hat-trick in 1879. Created in 1878, this caricature complements the team’s tour to England in that year and further celebrates the birth of Spofforth’s devilish moniker. Tom Horan wrote in 'Felix on bowling' (The Australasian, 2 October 1897) that during the second match of the tour the colonists won by nine wickets, with Spofforth picking up ten for twenty after first clean-bowling Grace for a duck. After he did so, Spofforth jumped about two feet in the air and sang out: ‘Bowled! Bowled! Bowled!’ Afterwards, in the dressing room he said: ‘Ain’t I a demon? Ain’t I a demon’ while gesticulating in his well-known demonic style and at the same time earning himself the sobriquet – ‘the demon’. Due to his technique of staring straight into the batsman’s eyes to try and scare him, Spofforth was the bowler the English team feared the most. In this caricature Ward has depicted him in his uniform and emphasised his great height (6' 3"), which gives us an indication of how imposing he would have seemed to English players at the time. However, Ward has also chosen to lampoon him by accentuating his large beak-like nose and lanky frame. Hence, we are awarded an entertaining image of the ‘demon bowler’, one of Australia’s finest bowlers of the nineteenth century.

The collection of Vanity Fair caricatures gives us another glance at these historical figures. Indeed Sir Leslie Ward’s witty and amusing representations present a different take on archetypal late nineteenth and early twentieth century portraits and further allow us to memorialise the place his subjects hold in Australian history. Such caricatures are a testament of the great artistic activity in this period of English journalism, which with the demise of Vanity Fair in 1914 has never been matched since.