The mid-nineteenth century man’s preference for being bearded might easily be dismissed as adherence to prevailing fashion, for any survey of portraits of the period will confirm that hirsuteness was mainstream.

Visualise some of those whom history has designated the defining British men of Victorian times – Dickens, Darwin, Carlyle, Disraeli – and you’ll see beards, just as you will when considering men like the explorers Robert O’Hara Burke and William John Wills, who are something of their Australian parallels for being lionised, mythologised, or celebrated. A survey of portraits can also suggest, though, that there is substantially more to the mid-nineteenth century’s embrace of the beard than affectation, conformity or laziness; and that the era’s facial hair renaissance proves something too about the deeper cultural conditions that were driving fashions in whiskers. The Victorian era’s sharper, more closely patrolled distinction between the worlds and experiences of men and women, for example, has been argued to have resulted in beards becoming a physical expression of the masculine attributes most prized by society at the time. The flipside of attitudes that enshrined characteristics like domesticity, vulnerability and chastity in women were those that measured male worthiness in dignity,decisiveness, independence and virility. Hairiness, by this reckoning, was next to manliness.

It follows that portraits provide evidence of the manner in which gentlemen, unconsciously or not, used facial hair to make manifest their masculine virtues; and that portraits or collections of portraiture can thereby prove a useful gauge when measuring the tempers of times. By the midnineteenth century, full and unashamed faces of hair were being adopted by men of all classes and professions, on grounds of health and hygiene and for their function as signs of authority, judgement and dignity. ‘Among many nations, and through many centuries, development of the beard has been thought indicative of the development of strength, both bodily and mental’, opined an article published in Dickens’s journal Household words in 1853. Beards, it claimed, were a ‘characteristic feature of man, and of man only, in the best years of his life, when he is capable of putting forth his independent energies.’

This theory offers some explanation as to why bearded faces seem to stand out in Australian portraits of the period; a manner that resists being simply construed as the bias of both era and genre towards the representation and achievements of men. The prevalence of bearded faces in Australian portraits of the mid 1800s perhaps says something too about the greater scope this continent provided for the ‘putting forth of independent energies’ and the more frequent, more dramatic opportunities it supplied for ‘real men’ to test their mettle: a vaster, wilder backdrop for the display of chivalry, intrepidity, heroism and pluck. Colonial conditions amplified the ruggedness, vigour or independence of manly endeavours, making the many portraits made of men like Burke and Wills those that seem to confirm the alignment of looks with codes of colonial masculinity.

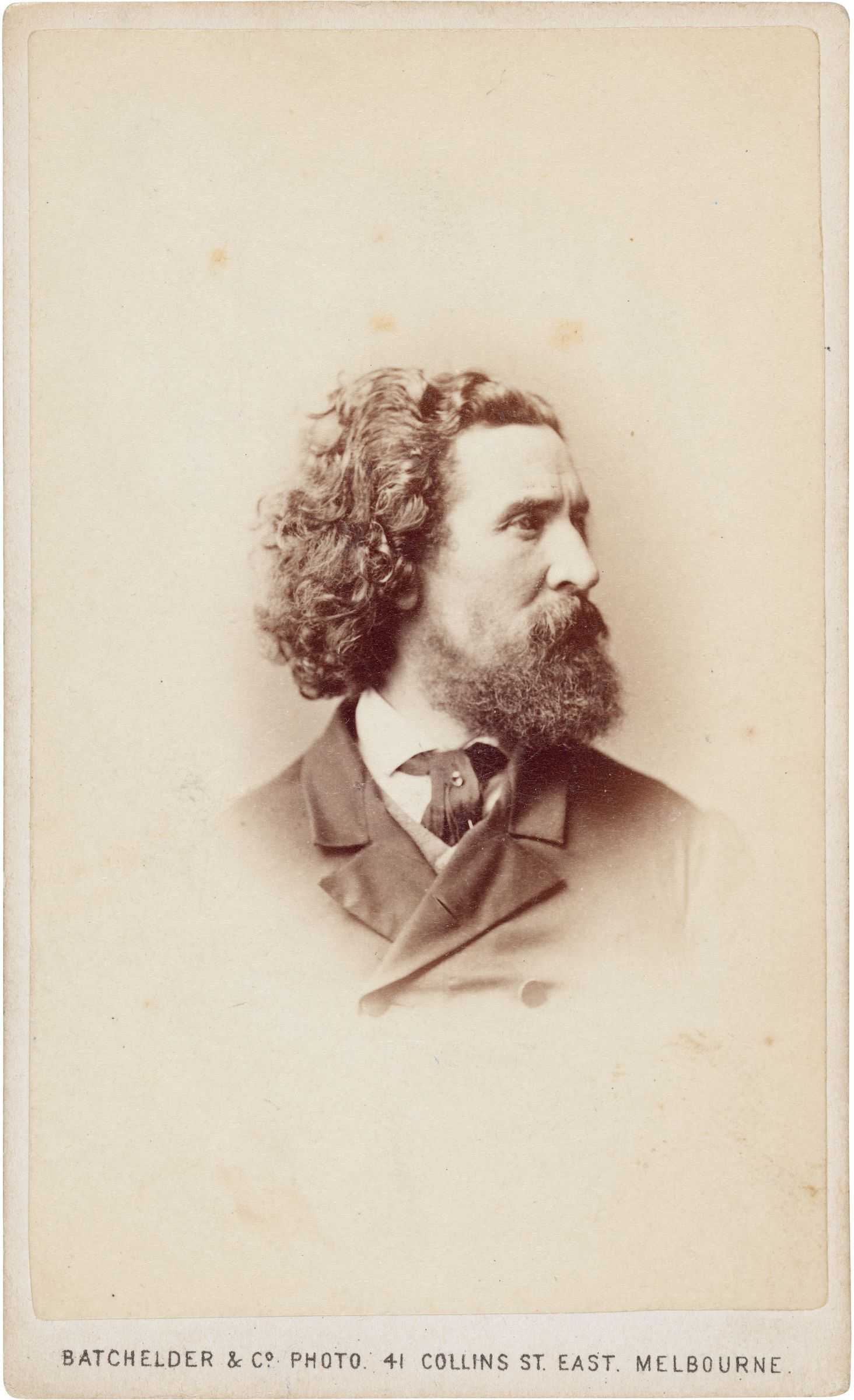

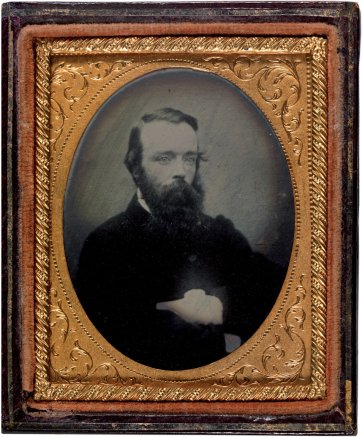

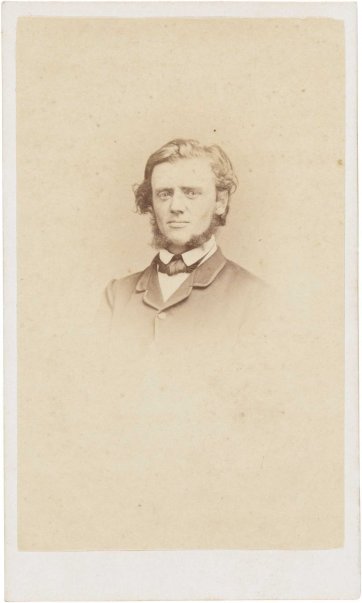

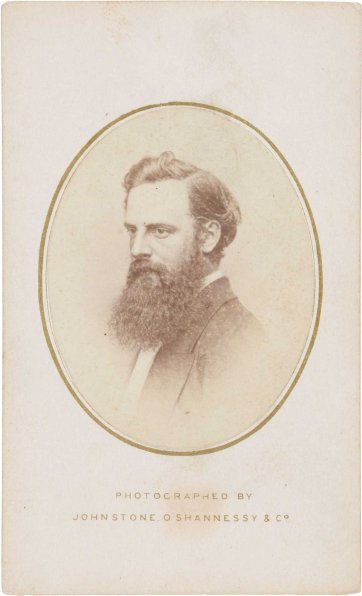

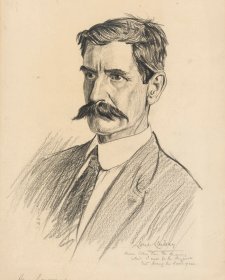

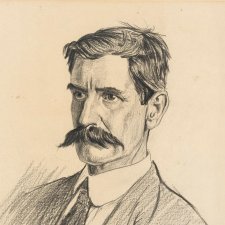

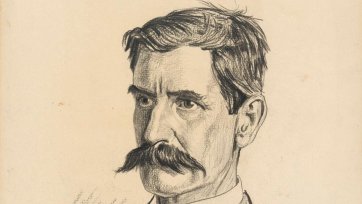

The photographer Thomas Adams Hill was one of numerous artists working in Melbourne in 1860 who determined that it would be worth his while to make portraits of them. Sometime around the middle of 1860, the two explorers-to-be visited Hill’s ‘Photographic Gallery’ on Bourke Street, where their likenesses were snared in two ambrotypes marking their successful applications to take part in what was originally known as the Victorian Exploring Expedition: Burke as leader; Wills as astronomer, surveyor and third in command.

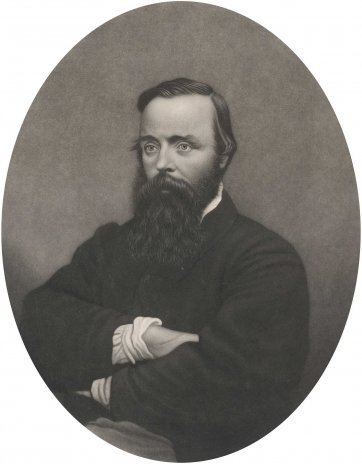

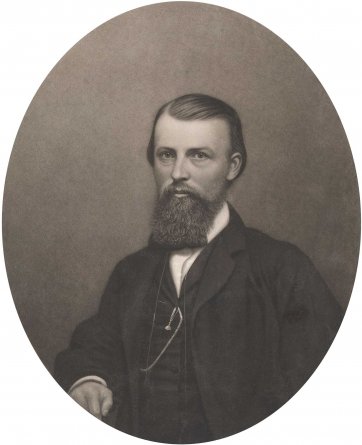

Hill’s photographs, taken in the thick of the pride and anticipation that characterised the lead up to his sitters’ ill-fated venture, later became the template for the many other portraits created in the frenzy of image and myth-making that occurred in the wake of its epically wretched end. Burke and Wills - and Burke in particular - as a result have ended up as arguably the most depicted of the hundreds of stone-faced nineteenth-century blokes who saw fit to secure for future reference a record of their looks and a souvenir of the weight of their lives and endeavours. The portraits of Burke and Wills by Hill are accordingly as much about how chuffed they themselves must have been about their journey as they are of the high esteem in which they and their expedition were publicly held.

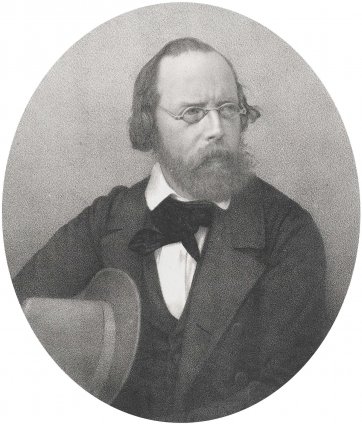

The proposal for what is now popularly known as the Burke and Wills expedition was first suggested by a Melbourne businessman who in 1857 offered £1,000 towards a venture best fitted to celebrating the independence Victoria had won from convict-tainted New South Wales six years earlier, providing that double the amount could be raised publicly to match it. The Royal Society of Victoria took up the challenge, raising the required £2,000 to which was later added £6,000 from the government. Such a war chest would ensure that the expedition, when it left Melbourne on 20 August 1860, was lavishly, though impractically, equipped. Recruitment for the expedition leaders began early in 1860 and concluded in June with the appointment of Burke to the commander’s role. An Irish landowner’s son and a former soldier, Robert O’Hara Burke (1821-1861) had been in Australia since 1853 and at the time of his appointment was working as a police superintendent in Castlemaine. According to one who endorsed his application, Burke was ‘a most active man, and very strong, most temperate

in his habits’ and ‘kind and gentle in his manners’. This referee also described him though as ambitious and ‘possessing a strong will’ – traits which in combination with his lack of exploration experience, impatience, limited knowledge of bushcraft, and primary motivation in the glory that the expedition would bring him, eventually resulted in decisions that led to its disastrous conclusion. William Wills (1834-1861) in contrast was modest, knowledgeable, serious and self-disciplined. Formerly a medical student, Wills had applied to join the expedition on the encouragement of his colleague, Georg von Neumayer, a German scientist and member of the Royal Society’s expedition committee and in whose Melbourne observatory Wills worked as an assistant.

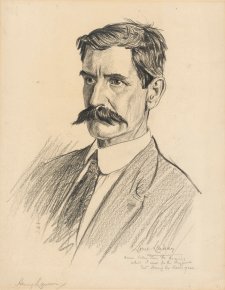

Whether a pure and nobly intentioned project conducted with the advancement of scientific and geographic knowledge in mind; a search for the vanished Ludwig Leichhardt; or, as detractors saw it, nothing other than an attempt to beat South Australia’s John McDouall Stuart in a race to traverse the continent from south to north, the Burke and Wills expedition soon took hold of Victoria’s imaginations. As historian Tim Bonyhady has observed, the expedition was the ‘stuff of art’ from its outset: ‘No other Australian expedition excited so much writing or so many pictures either before it started or while it was in the field.’ Portraiture accounts for a substantial proportion of this output. The expedition’s scale and audacity scored it and its primary players intense public interest and consequently the interest of artists eager to cash in on the swooning. William Strutt, for example, who arrived in Victoria in 1850 with several years of training and practice in France and England as a history painter, is noted for the many fine drawings and sketches he made during the expedition preparations. The subjects of these studies include

Burke; Ludwig Becker, the expedition’s artist and naturalist; George Landells, initially appointed Burke’s deputy and who had overseen the importation from India of the expedition’s camels; and the Indian cameleers. Painter Nicholas Chevalier, who with his Swiss heritage was associated with Becker, Neumayer and other members of Melbourne’s European intelligentsia, completed a depiction of the expedition’s pompous departure from Royal Park within three months of the event - an elaborate, large scale painting that includes individual portraits of Burke on his white horse, Landells immediately behind him astride a camel, and Becker likewise at the left. These and other images are evidence of Victoria’s enthusiasm for the project and its keenness to prove itself, via the exploits of these men, the wealthiest, most highminded of the Australian colonies.

But it is more than volume and variety that distinguishes images of

Burke and Wills from others with a presence in the Australian visual culture of their era. For one thing, the fervour fed by the start of the expedition had nothing on the image-making delirium occasioned when word hit home of its failures and the dreadful manner in which the explorers met their deaths. In short, Burke had ignored the instruction that the expedition base camp be established at Cooper’s Creek, in present-day south west Queensland. Instead, he jettisoned stores, experienced men and equipment, splitting the expedition at Menindee in New South Wales in October 1861 before continuing north with Wills (by now Burke’s deputy) and six others. Burke split the party again when they reached Cooper’s Creek in December, instructing four men to remain at the depot they made there while he, Wills, John King and Charley Gray made a bid for the Gulf of Carpentaria. They made it close enough to the coast to taste salt water, but with their progress obstructed by mangroves ‘could not obtain a view of the open ocean.’ On the terrible return to Cooper’s Creek, Gray died; Burke, Wills and King managed to get back to the camp to find that the relief party had left just hours earlier. What had started with so much hope and chest thumping ended up being that which resulted in the greatest loss of life of any Australian interior expedition. Burke, Wills, Becker and four others were dead within less than a year of leaving Melbourne: Burke and Wills both of starvation on Cooper’s Creek; Becker of scurvy and dysentery at a waterhole on the Bulloo River.

The portraiture that resulted from the deaths of Burke and Wills in particular – and which took the form of prints, paintings, sculptures, dioramas and waxworks tableaux - expresses that seemingly unplumbable nineteenth century capacity for grief and its rituals and the degree to which the two had been elevated as heroes. Such was the level of public grief at their deaths, for example, that the government funded a second expedition to recover their remains so that they could be brought back to Melbourne for an elaborate, befitting interment. In addition to being one of several artists who painted scenes of the death and burial of Burke at Cooper’s Creek, Strutt received a £50 commission from the Melbourne Club

to paint Burke’s portrait - an imposing, posthumous likeness reproducing Burke’s features as depicted in Hill’s 1860 ambrotype but with the addition of legs and a camel. It was a portrait considered by the art critic James Smith to have made ‘no attempt to idealise the subject’, presenting Burke with his ‘fiery outlook slightly dashed with melancholy.’ Printmakers too made use of Hill’s photographs, one of many examples being the commemorative mezzotints printed by Henry Samuel Sadd in 1861. Sculptor Charles Summers scored the lucrative job of creating Melbourne’s official monument to the explorers, a bronze sculpture of the pair atop a pedestal decorated with scenes from the expedition, since moved but originally erected in 1865 at the intersection of Collins and Russell Streets. And underlining the expedition’s German connections, lithographer Frederick Schoenfeld, another Swiss-born artist with scientific associates, produced a memorial portrait of Ludwig Becker for the Melbourne German Club.

As is often so with the commemoration and celebration of public figures, the writings and images made amidst the public mourning for the explorers were typically glowing and uncritical. Written and visual commemorations of Burke in particular took care to emphasise characteristics such as loyalty and heroism, a man ‘distinguished for intrepidity and a high sense of honour’ and not for the rashness, inexperience and poor judgement that hindsight has shown to be his flaws. Regardless, this portraitinfused community sadness has come to

have the effect of cementing in national memory and iconography the splendidly hirsute visages of him and some of his cohorts - the material culture of an epic, albeit tragic, venture which now makes it possible for us to discern what the Victorians liked most in their men.