Portraits. Today we take them for granted, but from the fifth to the fifteenth century - for much of medieval history - discrete portraits of individuals were a rarity, a form reserved for rulers and historic figures.

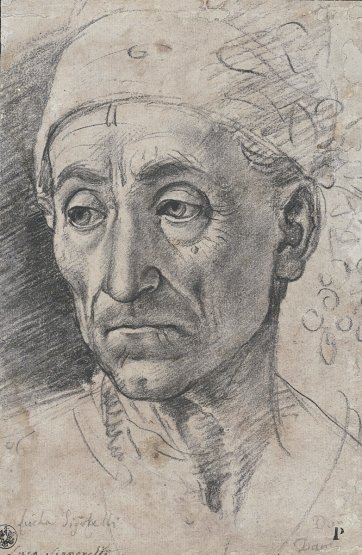

Only in the fifteenth century did European artists, working both north and south of the Alps, once again begin to produce independent portraits of men and women. The Renaissance Portrait from Donatello to Bellini at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, celebrates the Italian contribution to that first great age of portraiture in Europe, allowing visitors to experience the innovative responses of artists to the new challenge of recording an individual likeness and, in so doing, to explore issues of identity as well.

In fifteenth-century portraiture individuals step out from their subsidiary roles in altarpieces and mosaic and fresco cycles, where they had previously been shown as donor figures and consigned to subordinate positions, often on a diminutive scale, perhaps in profile or kneeling with their hands clasped. The visage and upper torso, treated in isolation, now filled the rectangle of an independent panel, which could be hung in the private room of a palace. Some of these early portraits were intended to commemorate a significant event, such as a marriage, death, or ascension to power. Others recorded for future generations the features of an esteemed member of a family or social organisation. In Venice, for example, the members of a group calling themselves the Compagnia degli Amici were required to have an outstanding artist paint their portrait and include in it an identifying inscription as well as the subject’s personal armorial device. Painted on a small enough scale, portraits could be carried about in a leather pouch as a keepsake or given as a token of friendship. In 1493 Isabella d’Este, marchioness of Mantua, exchanged portraits with her dear friend Isabella del Balzo, countess of Acerra, a town northeast of Naples. The countess sent Isabella her image on paper, perhaps a highly finished drawing. She also sent one in wax, which reminds us of the important role in the evolution of portraiture played by wax effigies: often lifesize votives set up in churches, none of which, sadly, survive. But it was the medallic portrait, an invention of the fifteenth century that became, quite literally, the currency of fame and the means by which rulers and the cultural elite made a bid for a foothold on posterity. Through the often abstruse allegories and mottos that decorate the reverse - sometimes devised by court scholars and poets - portrait medals were able to evoke to their recipients some particularly valued virtue or attribute. The marquess of Ferrara Leonello d’Este ommissioned no fewer than six portrait medals from Pisanello, the first great medalist, each with a profile portrait on the obverse and a completely different allegory on the reverse. King Alfonso of Aragon commissioned three, likewise employing different heraldic devices and emblems on each. Medals were not limited to rulers, however; Pisanello also made portrait medals of the great humanist teachers Guarino da Verona and Vittorino da Feltre as well as the outstanding military leaders of the day. Even artists were so immortalised, from Pisanello and Filarete to Gentile and Giovanni Bellini.

Just as the portrait medal became established in the Renaissance as a universal means of commemoration, enduring up until the twentieth century, so did the sculpted portrait bust, another classically inspired form. Writing in the first century AD, Pliny the Elder tells us that the ancient Romans displayed wax death masks in their houses and set portrait busts on the lintels of doors, traditions that were revived in Florence and elsewhere during the fifteenth century. A cast of the death mask of Lorenzo the Magnificent survives, and we know that Lorenzo placed busts of his mother and father over facing doors in the main apartment of the Medici palace.

The Renaissance Portrait brings together some of the finest portraits created in this first great age of portraiture, whether painted, sculpted, cast in metal, or drawn. The works were selected to suggest the dominant conventions and the striking innovations of a period spanning some eight decades. Given the geographic, political, and cultural complexity of fifteenth-century Italy, the organisers decided to divide the exhibition into three clearly defined sections. It opens in Florence, where independent portraits first appeared in abundance, and then moves to the courts of Italy - Ferrara, Mantua, Bologna, Milan, Urbino, Naples, and papal Rome - before finishing in Venice, where a tradition of portraiture was established surprisingly late in the century. In each section an attempt has been made to combine works in all media so that visitors can judge for themselves the ways in which conventions governing one medium interact with those dominant in another. In Florence, many will conclude (not without reason) that the most striking innovations occurred first in sculpture and were then taken up in painting. The sculptural busts of Desiderio da Settignano, for example, are where we first encounter a face enlivened by a transient expression and casual turn of the head. In the courts, thanks in large measure to the genius of Pisanello, the medal became the preferred means of recording a likeness, and we witness the phenomenon of painters designing medals, which were durable, could be produced in multiple casts, and were easily exchanged among a social elite. Some were gilded; exceptionally, Isabella d’Este had her effigy cast in gold and decorated with jewels.

In Venice the painted portrait held sway thanks to the achievements of Antonello da Messina and Giovanni Bellini, who resolutely abandoned the dominant Italian convention of the profile portrait in favor of the threequarter view, with the sitter's distant gaze and delicately modeled features expressing hints of an interior life. One of the tropes of humanist criticism was that painting could capture only external appearances, not the soul or the inner life of the subject. Although humanism, with its basis in the literary culture of Greece and Rome, provided a shared intellectual language throughout the Italian peninsula, political, economic, and social circumstances differed profoundly from one place to another, and these differences are inevitably reflected in the kinds of portraits favored in each region and the uses to which they were put. In a society dominated by social hierarchy and lineage, conformity to an accepted social template was the rule. In fifteenth-century Italy this was provided by the profile portrait, which was equally popular in its sculpted relief and painted forms. This must seem surprising to anyone familiar - as fifteenth-century Italians certainly were - with the far more naturalistic portraits of Jan van Eyck, Rogier van der Weyden, and Hans Memling, in which a softly lit subject, angled to the picture plane, is shown as though standing at a window or behind a parapet staring at the viewer, with his or her hand sometimes resting on the edge of the frame. Yet Italian portraits are not principally about resemblance, at least not in the straightforward sense we attach to that term. Rather than revelations of personality, they are conveyors of social conventions and cultural identities. The female subject of Filippo Lippi’s double-portrait in the Metropolitan Museum stands rigidly erect, her enigmatically expressionless face viewed in strict profile and her bejeweled hands folded neatly in front of her richly garbed body. Lippi was a gifted storyteller, capable of extraordinary expressive range, but that wasn’t the point here; instead, he transformed the individual portrayed into a sphinx-like cipher waiting to be decoded.

It is often said that the profile portrait enjoyed such prestige in Italy because it was sanctioned by the example of Roman coins and reliefs. Beyond that, however, the profile had always been the most essential way of transcribing a likeness. We have become so accustomed through photography to the more casual, direct, frontal portrait that we have to remind ourselves of the unique opportunities the profile provides for objectifying a person’s appearance and for transforming physiognomies into cultural signifiers: the elegance of a high forehead, the nobility or disdain of a raised brow, the aristocratic curve of a nose, and the strength or weakness of a chin and jaw - all physiognomic traits transformed into emblems of beauty, position, and power.

In the last act of The Importance of Being Earnest, Oscar Wilde is skewering of Victorian conventions of love, marriage, and class, there is a marvelous scene in which the socially conscious Lady Bracknell has a change of heart regarding her debtor-nephew’s infatuation with a lovely but untitled young woman. Upon hearing the news that young, unprepossessing Cecily stands to inherit a considerable fortune, ‘about a hundred and thirty thousand pounds in the Funds,’ Lady Bracknell decides that perhaps she ought to take another look at what had seemed a socially unequal, and therefore undesirable, match. True enough, the

girl’s clothes seemed ‘sadly simple’ and her hair ‘almost as Nature might have left it,’ yet as Lady Bracknell reminds herself and anyone within earshot, ‘we can soon alter all that’. She instructs Cecily to turn round. ‘No, the side view is what I want,’ she specifies. Then, after a pause: ‘Yes, quite as I expected. There are distinct social possibilities in your profile. The two weak points in our age are its want of principle and its want of profile. The chin a little higher, dear. Style largely depends on the way the chin is worn. They are worn very high, just at present.’

Chins were also ‘worn very high’ in fifteenth-century Italy, as anyone who examines the profile portraits of the young women in this exhibition - many of them painted to commemorate their engagements or marriages - will discover. We may laugh at the superficiality of Lady Bracknell’s criteria, but her assessment would have struck a sympathetic chord not only among the wealthy families in fifteenth-century Florence, where social connections, money, and appearance were primary considerations in any marriage, but also among the rulers of the smaller courts of central Italy, who were always attentive to potential dynastic alliances. We have a memorable record of this in the letters of Alessandra Strozzi, who was on the lookout for a Florentine wife for her son Filippo, then still living in political exile in Naples. In the summer of 1465, Alessandra attended mass in the cathedral with the explicit purpose of getting a good look at a prospective daughter-in-law. ‘She seemed to me to have a beautiful figure and to be well

put together. She’s as tall as Caterina [Filippo’s sister] or taller, with good skin, she’s not one of those pale ones, but looks healthy. She has a long face and her features aren’t very delicate, but they’re not coarse … and altogether I think that if the other considerations suit us she wouldn’t be a bad deal and will do us credit.’ Clearly, Alessandra had an ideal template against which she measured

the appearance of any prospective daughter-in-law, and it was with just such a template in mind - a poetics of beauty shaped in no small measure by the poetry of Petrarch and his imitators - that artists adjusted the features of their subjects.

What distinguishes Italian portraits of the fifteenth century from those created north of the Alps is an emphasis on artifice of style and artistic ingenuity – what in the critical language of the day was referred to as artificio and invenzione – as a means of transforming mere observation into something beautiful to behold. An artist’s reputation depended less on a factor of realism than his success in creating an image worthy to be passed down to posterity. It was to compare Leonardo’s qualities as a portraitist with those of Bellini that the fastidious and difficult Isabella d’Este asked Cecilia Gallerani, mistress of Ludovico Sforza, to send the portrait he had made of her to Mantua. The following year Leonardo made a magnificent drawing of Isabella in which he combined her profile with a frontally viewed torso, thus mixing modernity with court tradition. As Leon Battista

Alberti declared in his 1435 treatise De Pictura, ‘Painting possesses a truly divine power in that not only does it make the absent present (as they say of friendship), but it also represents the dead to the living many centuries later, so that they are recognised by spectators with pleasure and deep admiration for the artist.’

The Renaissance Portrait from Donatello to Bellini The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York December 21, 2011–March 18, 2012. The exhibition was organised by Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Gemäldegalerie and The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.