‘I have seen too much not to know that the impression of a woman may be more valuable than the conclusion of an analytical reasoner’, Sherlock Holmes declaimed in The Man With the Twisted Lip, published in the Strand magazine in December 1891.

Never mind that what Holmes means by this statement is that what a woman believes, instinctively, to be the case in a given situation sometimes turns out to get you further than a judgement a man makes on consideration

of demonstrable facts. It all goes to indicate the slipperiness of the term ‘impression’, and its broad applications.

Impressions: Painting light and life comprises portraits made by and of Australians, in and around Melbourne, Sydney, Ballarat, London and Paris, in the years between 1885 and 1910. It includes portraits by, and of, the artists known as the Australian impressionists – including Tom Roberts, Arthur Streeton, Charles Conder, Frederick McCubbin – along with men and women from their wide circle. The artists and sitters in the portraits in Impressions attended classes, formed clubs and societies, exhibited and took painting trips together; forged friendships on the eight-week sea voyages between Australia and Europe; and sought each others’ company abroad. Making the personal connections is addictive, and the researcher is teased by possibilities of encounters that were never recorded or divulged. This much is sure, however: they were people to whom the direction in which art was heading seemed vitally important, and many of them sacrificed a great deal to pursue their careers and calling.

The portraits in Impressions are in a variety of mediums, and some appear to be much more ‘finished’ than others. Art students of the time learned their craft by copying works by old masters, or drawing and painting studio props such as the statue and still-life tableau in Herbert Smith’s The Art Students (while red-headed Florence Allender concentrated on her still life, Smith fixed his attention on his lovely pupil – they were to marry in 1905). It would have been hard for artists, and particularly for critics, trained this way to come to terms with the idea that hasty little working paintings like Study for 'The love story' have charms all their own, independent of the finished paintings for which they were ‘impressions’ in the original sense.

Tom Roberts, invigorated by a study tour of Europe – during which the brilliant Spaniard, Ramon Casas, happened to paint his portrait with bold strokes, on the spot – burst back on the Melbourne art scene in the mid-1880s. In 1889 he was the prime force behind the 9 by 5 Impression Exhibition in Buxton’s Rooms in Swanston Street, Melbourne. Exquisite elements of décor were borrowed from an exhibition of Whistler’s that Roberts had seen in London in 1884. Louis Abrahams’s father had a cigar business and was able to supply the artists with flat box lids, sized about 9 x 5 inches, which were ideal for intense, focused rendering of momentary detail. The title of the show, with a catalogue designed by

Charles Conder, proclaimed that the tiny, moody panels were never intended to go any further; they weren’t studies for works yet to come, but paintings with their own virtues, intended for sale at one or two guineas each. In one of the most eloquent paintings in that watershed show, Conder declared his friend Roberts to be An Impressionist. And justly so: in a creative fever, spurred by pecuniary considerations, Roberts had captured sixty-two impressions by the opening deadline. One of them, La Favorita, is a vignette of a shadowy senorita, with red dress and hair ornament. Spain had been a revelation to Roberts. La Favorita, an opera by Donizetti, premiered in Europe in 1840 and in South Australia in 1873.

La Favorita was also a brand of Cuban cigars available in Melbourne at the time. All these factors casually cohere in this modest painting on a cigar box lid, by a handsome wag of an artist in the zesty early phase of his career.

The 9 by 5 Impression Exhibition challenged visitors to consider the point at which an artist’s quick response to a momentary combination of colour, light and form becomes a work sufficiently finished to show to someone else. The

sheer variety of works in Impressions: Painting light and life allows for further thought on this question, which was an important one to the artists represented. At what point do we forget to admire the way an artist has painted or drawn, and see, suddenly, in a whole new way, because of the way they have shown us to look? There is a page of sketches John Peter Russell made of his friend from Paris, Vincent van Gogh, that afford an electrifying glimpse of the impression the man made on Russell right there, right then. At what point does an ‘impression’ of a certain look on a face become a portrait of a person? George Lambert’s Study for Alethea is only a rough sketch that didn’t translate to a finished painting. It isn’t the case that Lambert, out and about with his painting kit, ran into Proctor exercising her borzoi on an English moor. He posed her, with the fashionable hound of the day, in the manner of a portrait by the Englishman Charles Furse, who specialized in breezy, swaggering portraits of men and women outdoors. All the same, her friends though it evoked the ‘essential woman’ more

vividly than any other of Lambert’s many paintings and drawings of Thea Proctor. Study for Alethea stands as evidence, in fact, that the painted impression of a woman may be a better indicator of personality than a finished portrait made by an analytical artist – which Lambert assuredly was.

The effectiveness of a vigorous alla prima stroke in rendering the vitality of a portrait subject had long been recognised. The seventeenth-century Spanish artist Diego Velázquez is often credited with doing away with painstaking, smooth and fussy replication of every last detail in portraits, and introducing a freer style in which personality prevails over trappings of eminence. As early as 1825, Velázquez’s compatriot, Francisco de Goya y Lucientes, described his own experiments with ‘loosening up’, writing to a friend that he had amassed ‘a collection of about forty experiments… everything is made up of dots and

things, that look like the brushwork of Velázquez’. By the 1870s, the French portraitist and teacher Carolus-Duran, mentor of the brilliant portraitist of fin-de-siécle high-society, John Singer Sargent, was advising his pupils to ‘study Velázquez without respite’; which Sargent did.

The dashing brushwork of Velázquez seized the imagination of the young Australian artist Hugh Ramsay, who arrived in Paris from Melbourne via London in January 1901. Over three heady years, both exhilarating and damaging, Ramsay painted many self portraits in his chilly Paris studio. Some are highly finished, others are rapidly sketched, but they all show his attempts to master paint and use a rich range of tones in rendering fabric, shadows, glimmering gilt and candlelight. In 1902 four of Ramsay’s paintings were chosen for exhibition at the competitive New Salon in Paris. This extraordinary achievement earned him the patronage of Dame Nellie Melba, who itched for a portrait by him. When Ramsay became gravely ill, she funded his return to Victoria.

Here, against his doctor’s advice, Ramsay pursued a punishing work schedule, attempting, amongst other works, a giant, almost life-size Equestrian

Portrait of his doctor’s son, his sister Madge and two horses with some delightfully art-nouveau styled gum trees in the distance. In 1904 his six pictures in the Victorian Artists’ Society exhibition included the equestrian portrait and his magnificently assured picture of his sisters, candlelight reflecting from their robes of white satin. Ramsay referred to the work in letter as ‘Mag and Nell’. Madge and Jessie Ramsay, in fact, posed for the work in the first instance, but the figure on the right, with Jessie’s body, has Nell’s head – making it a composite painting of his three siblings. ‘One can only speculate on Ramsay’s own feelings’, writes his biographer, Patricia Fullerton, ‘as he accurately portrayed the solemn

features of his young sisters dressed for what should have been a gayer occasion altogether than these sittings in front of a dying brother.’ Though the rug looks to be borrowed from Whistler’s White Girl of 1862, and the lassitude of the girls recalls the attitude of the woman in Ramon Casas’s Joven Decadente (Después del baile) [After the Ball] painted in Paris in 1899, the swiping strokes of the work, the slashes of dirty yellow and brown that make up the different textures of white stuffs of sleeves and skirts, call to mind the work of Sargent, at the height of his fame during Ramsay’s time away. Ramsay was a fervent admirer of

Sargent’s, not having a bar of the notion that he was ‘too clever’, writing of the

‘absolute mastery’ of his paint handling. In the eyes of the young artist, ‘he gives us the beauty of life, the palpitating flesh, the beauty of light and colour, the lovely truth of atmospheric envelopment.’ Remote from the glamour of Europe, Ramsay died of consumption in the fresh air of the Victorian countryside at the age of twenty-eight. It was widely acknowledged that he had the most potential of the artists of his generation. ‘Had he lived longer’, said Lambert, ‘he would have beaten the lot of us.’

There is nothing in the portrait of the Ramsay girls that betokens an Australian

interior - no jar of gum tips glimmers in the shadows. Nor, surprisingly, is there a bright Australian portrait of a person outdoors in the manner of countless European and English portraits of the centuries to 1900 - to take but one example, Sargent’s 1879 painting of Madame Edouard Pailleron at her family seat near Chambéry in Savoy, the grand pile of the house just visible through the trees. As Holmes himself might have said, the irrelevance of the portrait of Mme Pailleron to the works in Impressions is instructive. Through the 1890s, as Tom Roberts painted his major works outdoors, he worked steadily at portraits, achieving gorgeous results, such as Miss Florence Greaves, without a trace of strain. However, neither he nor any other artist made a significant portrait in a landscape, its subject posed amongst eucalypts or wattles, crossing golden grass, sitting by water or in sunshine. The closest any of them came was depicting their friends and family members, at a distance, their faces indistinct, in the bush. Frederick McCubbin’s sister modeled for Roberts’s painting of a woman amongst saplings, A summer morning tiff; but the picture of the girl in dazzling white was in fact no more and no less than Roberts’s first concerted attempt to capture the appearance of sunlight on trees and grass. Further, though painters, patrons, journalists, musicians and students knew each other well, there is no Australian equivalent to the quintessential Impressionist group portrait, Renoir’s Luncheon of the boating party (Roberts’s great group picture is Shearing the rams). Finally, there is little skin. In this hot country, there is barely an ankle or a creamy throat exposed on canvas; no woman wears stripes, few wear frills, none raises a champagne glass, none sprawls on the grass, few are dancing or flirting in a crowd. Even at their loveliest, women in Australian portraits of the period are diffident and primly dressed. Early in the 1890s, the decade in which Roberts brought forth his great portraits, he painted the loveliest: Eileen Tooker with her black dress mounting to her throat, her coat collar turned up to cover her hairline at the nape, and her face darkly veiled. Like the figure in Fullwood’s Reflections, Eileen could be a Londoner, an enigmatic client in a Conan Doyle story.

Indeed, a few years after this portrait was painted, Eileen Tooker was involved in an incident that has the makings of a case for Holmes. The Sydney Morning Herald of 2 March 1896 reported that Mrs Tooker, alone in the pre-dawn hours at 244 Point Piper Road, Woollahra, had heard a noise in a room below. Seizing a loaded revolver, she stole downstairs, where she alleged to have found two men in the process of ransacking the room. In a struggle, she shot at one man, but the other set upon her; having placed – she claimed – the gun under her left arm in an attempt to shoot the intruder behind her, she shot herself in the ‘fleshy part’ of the limb. Both miscreants fled. Neighbours, having heard the gunshot, arrived quickly. ‘The strangest part of the whole affair’, the paper reported, ‘is that no one saw the burglars leave the place, nor can the police find any evidence as to the means by which they obtained an entrance’. Mrs Tooker, suffering from

shock, removed to a private hospital at 20 Macleay Street to recuperate. Or, perhaps, to get her story straight.

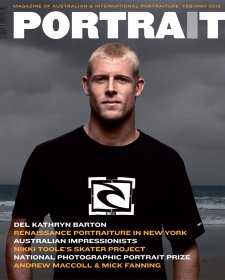

Between them, the artists represented in Impressions brought forth many of the most popular works of art made in Australia between European settlement and Gallipoli. Their portraits and figurative works are a window onto a world of smart bustled frocks, graceful veils, fetching hats, pretty children, well-behaved cats and dogs, and gentle trysts in dappled pockets of bush. Captivating treasures of Australia’s public galleries, such paintings, drawings, prints and sculptures are together, their intertwined subjects and artists reunited, at the National Portrait Gallery until 4 March 2012.