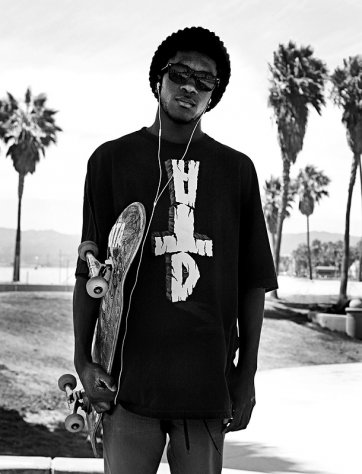

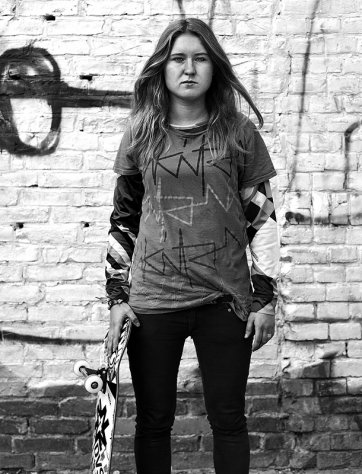

Since July 2009 Melbourne-based photographer Nikki Toole has been making photographic portraits of skateboarders around the world. Her subjects are captured in still frontal pose against the textured backdrop of the urban environment or in landscapes at the edge of cities. Toole’s portrait project is driven by the desire to understand and commune with her subjects.

She is interested in the forces of identity that define the lone skateboarder. ‘Many skaters speak of a solitary mind space while skating; of entering into another state of consciousness’ Toole says. ‘To make these portraits I asked the skaters to place themselves within this meditative space.’ A group of nineteen portraits are exhibited at the National Portrait Gallery, the first time images from the Skater project have been exhibited as a group.

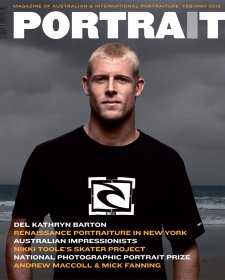

Nikki Toole was born in Scotland in 1965, and now lives in Melbourne. She has studied art and design in London and Edinburgh, and has exhibited in Australia, Britain, USA and Germany. Toole’s portraits have been selected for the National Portrait Gallery’s National Photographic Portrait Prize exhibitions of 2007, 2009 and 2010.

The Skater project has been in process now for three years, and it’s ongoing. How did the Skater project start?

I moved from London to Melbourne in 2004. Living in the suburb of Fitzroy in Melbourne, I often saw skaters using their boards as a mode of urban transport. This was something I hadn’t noticed as much while living in London. I had been a skater when I was younger, and I also noticed that the culture had changed since my skating days. Some aspects had become very corporate. I was interested in the individual drive to skate that had originally motivated me. There is a sense of being part of a larger culture but also of being totally at the mercy of your own headspace. I talked to other skaters about this feeling and many felt it was a form

of meditation or a release in some way, getting into a particular mental space, getting into the zone. I was interested to see if there was a way to capture this sense of being in the zone while skating without taking photographs of the skaters in action. I was also interested in local cultural differences in skater culture, in terms of fashion styles and personal expression. Is there a global look or is there still a place for the individual or the loner to express him or herself? I chose to photograph the skaters in a setting that does not always reveal the geographic location, although this information is often included in accompanying text when the portraits are presented. Each skater would stand facing the camera while calling to mind the mental zone they found while skating. As the project developed, I discovered that a shared interest in skating meant that the project was easy to explain to skaters of any age, gender or culture. The photographs have been presented online and in magazines, and my plan is to produce a book of photographs.

You have photographed skaters in different parts of the world. How did you go about seeking out skaters to photograph?

In the beginning I photographed friends who were part of the local skate scene. As the project developed I designed a website to reach out to skaters overseas, publishing skater portraits I had already made and asking for interest from potential subjects. The first overseas trip for the project was to the USA. I had reached skaters using Myspace and by contacting skate companies. We managed to line up photo-shoots in Arizona, Utah and California. While shooting in Flagstaff, a skater we met spread the word and we made a lot of useful contacts that way. As long as they could skate I was happy to photograph them. Each skater received a digital file of their portrait and this proved to be a motivation for many to participate in the project. While on the road we would often drive through a town and drop by the local skatepark to see if any skaters were interested in taking part. I learned to shoot fast and take very few shots. I also had made some small sample books of the portraits to show to skaters we met at their local parks. This made explaining the project easier, especially in Prague and Rome. The kindness of other skaters made this project possible, as many went out of their way to make other skaters aware.

Skating has typically been associated with male youth communities but the skater project represents a wide range of people. Did you set out to document a diversity of types of people across skater communities?

My primary focus was an exploration of the mindset, the culture and the sense of self identity of being a skater. Initially many of the skaters assumed I wanted to photograph well known, high-profile skaters, and I did end up photographing a few top skaters, but this was as part of the process of photographing a broad selection of skaters who were willing to participate in the project. I am not from Australia and the cultural differences in the Australian skater scene were very striking to me. As the project began to take shape as an idea for a book, my aim was to travel with the project as much as my funds and commitments would allow. This in turn led me to meet skaters of all ages, gender and skill levels. I am planning to continue the project with a forthcoming visit to Japan. The diversity of the types of skaters I have photographed has been a natural outcome of the project.

The portraits in the Skater project follow a consistent stylistic pattern. Was this visual style in your mind from the start of the project?

The visual style of the photographs was an aspect of the project I was very clear about from the beginning. I did not want the distraction of colourful clothing. The skater and his or her expression was the story that I wanted to tell. They are all part of the same story; therefore they had to have a common ground. In some ways to have them face me simplifies the engagement. They stare at me, but their mind is engaged elsewhere, we form a brief connection before the event of taking the photograph and disengage during this process. I ask them to relax and hold their board, not to pose with it. I suppose there are only so many ways they can hold it. Personally I am drawn to photographic portraits where the subject is looking directly at me.

What was one of the most unexpected experiences you had while producing the Skater project?

The famous Mystic Skatepark in Prague is located on an island in the Vlatava River. My partner Andy and I arrived during the Czech Republic skating championships. We were given permission to photograph the skaters and found a quiet spot close to the main skate ramp. Tomas Vintr, one of the Czech skaters, explained my portrait project to a few of the participants. An unexpected and great occurrence was that the skaters would skate their turn in the event, and run over to us between events and I would shoot five or six images of each skater. The language barrier wasn’t an issue because we had Tomas translating, and the skaters quickly understood the idea behind the photoshoot. The energy and excitement of taking these photographs is one of my most treasured experiences.

Skater: Portraits by Nikki Toole is on display at the National Portrait Gallery from 16 February - 29 April 2012 and Geelong Gallery from 30 June - 9 September 2012.