David Low’s job was to make people look foolish, and he was so good at his job that when he died – as Sir David Low – he was acknowledged as the dominant cartoonist of the Western world.

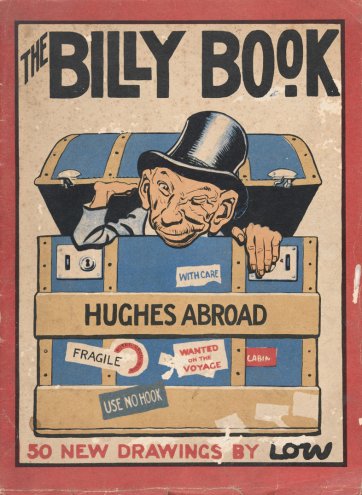

Drawing professionally from the age of eleven, first in New Zealand and then in Australia, he made his name with his second published anthology of caricatures, The Billy Book (1918) a bestseller that enraged its subject, the bellicose Australian prime minister, Billy Hughes. The success of The Billy Book brought Low a contract with the London Star, and he left Australia in 1919, never to return. In due course, his cartoons infuriated Hitler, too.

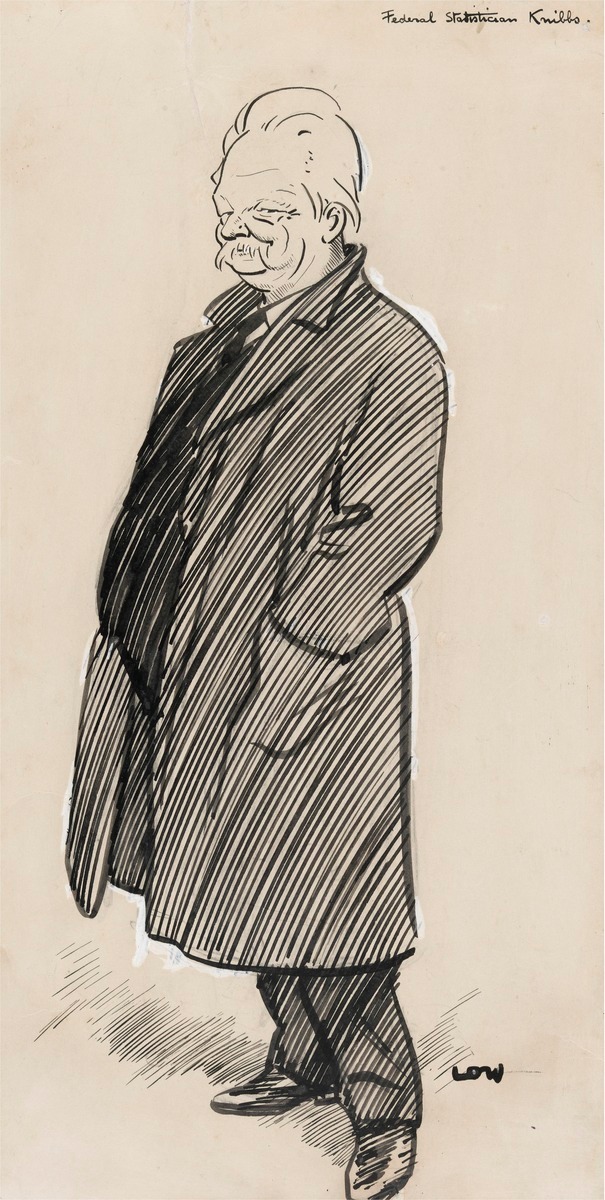

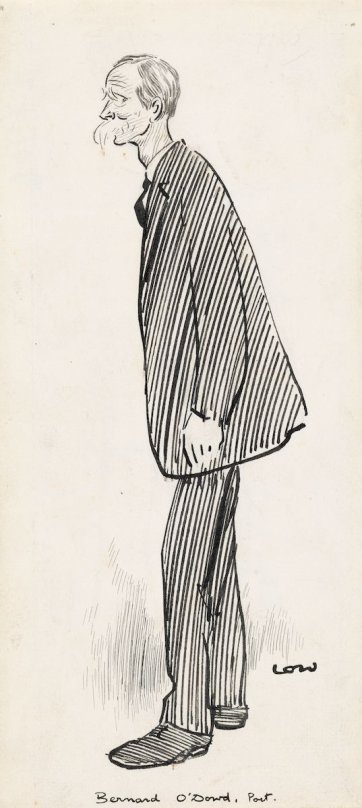

The National Portrait Gallery has several of Low’s Australian portrait drawings, as well as a copy of The Billy Book. The year he left Australia, Low drew the gaunt and radical poet, Bernard O’Dowd; and also the Commonwealth Statistician, George Knibbs, looking like a cat with creamy whiskers. Reputedly there was an element of self-satisfaction about Knibbs; but he was the total opposite of a fool.

Sir George Knibbs CMG (1858-1929) was born into a working-class Sydney family in Redfern. Oddly enough, little is known of his schooling. He joined the public service at nineteen, and was licensed as a surveyor the following year. At twenty-three he joined the Royal Society of New South Wales; he edited its journal for nine years, and was its president in the late 1890s. Over that decade he lectured in various topics, including surveying, in the engineering school of Sydney University and in 1905 acted as professor of physics there. At the same time, he was appointed NSW’s superintendent of technical education. By the age of forty, Knibbs had a passion for pure mathematics, about which he spoke in profound terms. In an 1898 lecture he said that ‘as one penetrates more and more deeply into its mysteries, one feels less and less concern as to whether it can be applied to the attainment of material ends … It discloses forms of knowledge existing, as it were, latent within our souls, and since its truths, when realised in conception, cannot be withstood, they afford a startling evidence of the unity of consciousness.’

These are surprisingly poetic ruminations from the man who, three years later, turned his hand to Price-indexes, their nature and limitations, the technique of computing them, and their application in ascertaining the purchasing-power of money, a slim volume of incredible density, printed in miniscule font, replete with tables and formulae. It is the Knibbs of Price-indexes who, in 1906, was appointed first Commonwealth Statistician, directing the work of the newly-established Commonwealth Bureau of Census and Statistics. The first Commonwealth Year Book, one of Knibbs’s triumphs, was issued in 1908.

The first Commonwealth census – a ‘great Imperial stock-taking’, as Knibbs described it – took place in 1911. In his discursive introduction to the event, he observed that historically, leaders had needed headcounts of subjects so as to assess their prospects of marshalling an army. Rather than a ready reckoner of potential for aggrandisement, he wrote, the modern Census was a sociological tool, a ‘studied representation of our national life and social organism’ that would comprise the minimum information necessary for the intelligent administration of government. Knibbs regretted that the exciting truths presented in the Census might reveal themselves to few. Rather wistfully, he wrote that ‘the form in which this picture is drawn may, to some extent, be repellent to the average man, who often fails to discern the inward meaning of columns of figures and the significance of the lessons they teach’. He regretted that amongst the common herd, ‘there appears to be an instinctive aversion to what may be styled arithmetical literature’.

Knibbs was interested in nonarithmetical literature, too. He published translations of Greek and Finnish verse, and wrote some of his own. The journalist Arthur Jose assessed Knibbs’s own literary efforts: ‘Noteworthy in themselves they were not. But their existence, their pensive disclosure of one side of his brain, make them important for any discussion of him. They round him off, and do away with the last lingering suspicion that he was after all a splendid super-machine.’

Alongside his central involvement in Australian statistics, insurance, taxation, superannuation, education and other issues, the ‘splendid supermachine’ travelled widely overseas in the course of his career, attending multifarious congresses – for example, in the year that Low drew him, the double income tax and war-profits conference in London – and becoming a member of many international societies. Jose judged that amongst public servants, only Sir Robert Garran was more frequently consulted on more various subjects or sent on more diverse missions. In 1921, Knibbs resigned as Commonwealth Statistician to become director of the new Commonwealth Institute of Science and Industry, a position he held until 1926, with a knighthood coming in the meantime.

Of engrossing interest, now, amongst Knibbs’s publications is his tract on sustainable global population, The Shadow of the World's Future or the Earth’s Population Possibilities, published in 1928. In this, his last major project, Knibbs contended that for the first time in man’s history, his great problem is ‘how to carry on the issues he has raised’. The time available for adjusting to reality, he wrote, was very short. ‘Mankind is profligate in the use of such of Nature’s materials as are immediately at his disposal, and he is applying them, and the foodstuffs likely to be available, recklessly. For this reason Man will certainly be pulled up in the near future.’ (Knibbs usually said ‘Man’ when he meant ‘people’.) The problem was, however, that ‘the building up of the character of a people is a slow process and one which involves centuries of experience and effort’.

Amongst Knibbs’s propositions in The Shadow of the World’s Future is that if the world’s population were to reach 7 800 million, there would not only have to be a much more efficient use of its surface, but a deeper study of the climatological factors which might aid in the increase of its food supplies. (In 1912, Knibbs had put together a Mathematical analysis of some experiments in climatological physiology). He assumed that as the world’s population-density increased, people would economise on energy and occupiable earth-space by becoming more vegetarian and eating more fish. For Knibbs, the practicalities of living on a crowded planet were necessarily underpinned by a change in focus from the individual to the complex whole: ‘world-solidarity’, which, he sensed, was on the rise in his own time. The man who had spoken thirty years before of the ‘unity of consciousness’ and lectured on The place of astronomy in a liberal education had the entire earth in mind. ‘The time has gone by when Man could regard the world as being for his benefit alone … or even primarily for his benefit,’ he wrote.

As for the petty squabbles of humanity, they were insupportable; he looked to ‘the virtual elimination of all forms of unscrupulous egoism in the life of nations and in the relations of races which menace the well-being of the whole.’ Further, for individuals living in dense populations, ‘the prevailing aims of human lives will have to be less concerned with complications in the mere standard-of living. A more humble life, physically, with a deeper regard for the higher issues, is a sine qua non, if it be really desired to see the earth covered with contented peoples, whose well-being is assured and whose living is a disclosure of generous attitude and noble purpose.’

It is a lovely phrase; and indeed, Knibbs’s eulogy referred to his love of the arts, his grasp of the humanities, his keen interest in the problems of religion, and the warmth of his happy home. He was a family man who was also described as one of the greatest minds of his time. The variety of his papers is astounding. Yet it must be said that amongst statements of startlingly enduring relevance, Knibbs gives rein to ideas that stamp him as a child of his time. In 1921, the year he was appointed Director of the Commonwealth Institute of Science and Industry, Knibbs served as vice-president of the second International Eugenics Congress in New York. Sequel to the London congress of 1912, and precursor to the New York congress of 1932, the second congress had Alexander Graham Bell as its honorary president. The vast majority of its papers were presented by Americans, who were the experts in the field.

Knibbs’s interest in eugenics does not define the man. Yet for twenty-first century readers, his pronouncements on the enhancement of the gene pool require more contextual explanation than his other enquiries and interventions. By the time Knibbs presided over sessions of the Eugenics Congress of 1921, sterilisation laws had been enacted in many American states (60 000 Americans in thirty states were sterilised without asking for it over the course of the twentieth century). Over the 1920s, State fairs featured eugenic displays, offering personal pedigrees and, for those certified fit, medals engraved with the words ‘Yea I have a goodly heritage’. Eugenics mania had its long and fibrous roots in the peak years of immigration to the USA. In 1924, halfway between the second Eugenics Congress and the publication of Knibbs’s Shadow of the World’s Future, Harry Laughlin, Director of the Eugenics Record Office in Cold Spring Harbor, New York, testified to Congress that disproportionate numbers of ‘feebleminded’ and criminal citizens were flooding from southern European countries into America. So it was that immigration, and the relative ‘fitness’ of various groups of people, became a key theme of the third and last Eugenics Congress, held at the American Museum of Natural History. In Germany between 1934 and 1939, 400 000 feebleminded, epileptic, alcoholic and other ‘defective’ citizens were sterilised. During this period, Harry Laughlin’s seminal contribution to the German program was acknowledged with an honorary doctorate from Heidelberg. In 1940, when hospital beds were needed for its soldiers, the German state began gassing those whose lives were ‘not worth living’. The rest, as they say, is history.

Knibbs’s first strategy for the enhancement of character in coming generations was ‘intelligent mating’– an attractive idea even now. Consistent distribution of the world’s population across the surface of the globe was central to his unwavering hope for a peaceable world. In warning, however, that ‘no country can without peril accept migrants without regard to their character’, he appears to be taking his cue from Laughlin’s Congressional testimony. Knibbs wrote that if countries were obliged to retain responsibility for their defective and degenerate elements instead of attempting to foist them on others, they would be forced to focus on what to do about them. (Australians, of course, had not been troubled by substandard immigrants since the passing of the comprehensive Immigration Restriction Act of 1901; prospective citizens are still constrained to take a character test.)

Knibbs acknowledges the influence of Dr FG Crookshank’s The Mongol in our Midst, published in 1925. In 1927, in Virginia, justice Oliver Wendell Holmes delivered his famous judgement that ‘three generations of imbeciles are enough’. These sources presumably inform Knibbs’s proposition in The Shadow of the World’s Future that ‘the time has arrived when defectives and degenerates should not be allowed to reproduce their kind’. He is probably referring to Crookshank when he writes that ‘all who have really studied the question’ are beginning to realise that ‘the future of the human race should be safeguarded from the mischief that such people perpetuate’. As these ideas jostled for space in the commodious brain of the Director of the Commonwealth Institute of Science and Industry in the 1920s, eugenic tenets became broadly accepted as positive initiatives for a strong Australian population.

The Racial Improvement Society, later the Racial Hygiene Association of New South Wales (and then, from 1960, the Family Planning Association) was founded in 1926 by Lillie Goodisson of the Women’s Reform League. Lillie Goodisson favoured sterilisation of the mentally deficient – but the idea never took off here. Shudder as we might at some of his assertions, it would be fascinating to hear a reincarnated Knibbs’s perspectives on contemporary initiatives that ‘genome generation’ Australians take for granted, such as the nationwide Jeans for Genes Day and routine prenatal testing amongst women over thirty for Down syndrome and neural tube abnormalities.

Knibbs’s persistent theme was that Man’s moral development had not kept pace with his scientific knowledge; that there was a pressing need for ‘humanity … to be both instructed and governed’. On one hand, as he looked into the future of an ignorant and selfish world, he felt that the situation was well-nigh hopeless – not because the problem of overpopulation was essentially insoluble, or beyond the reach of the intelligent, ‘but because humanity is mentally and morally what it is at the present time’. On the other, it seemed to Knibbs that thinking men had, at last, reached more sanity in their estimate of their place in Nature, and in regard to their status as denizens of the earth, than they had expressed in the past. The ablest of them, he wrote, ‘are able to envisage to some extent the problems of their own future … To those who have vision comes the call of duty, viz., that of shaping the interest of their country and the world in respect of the tremendous problems that loom large in the future life of humanity.’ Knibbs said it in 1928.