A century ago Australia was still very much a new nation. Although the Federation movement was marked by dissent and the competing priorities of the separate colonies, it had arisen from a growing nationalism in the late nineteenth century. In the first decade after 1901, the topic of appropriate recognition of the people and events associated with creation of the Commonwealth was periodically discussed by the new Parliament. One advocate for some form of commemoration was artist Tom Roberts, perhaps motivated by his own efforts in creating the 1901 ‘big picture’ recording the Opening of the First Commonwealth Parliament. Roberts wrote to Alfred Deakin in March 1910, ‘let me ask you to consider the importance of acting early … and let these records be painted … to give faithful representations of the first leaders of the Commonwealth.’ Deakin sent a copy of Roberts’ letter to Prime Minister, Andrew Fisher, who told the Parliament in October 1911 that ‘the government hopes to preserve … likenesses of the prominent statesmen of Australia.’ Two months later the Historic Memorials Committee was established as a ‘committee of consultation and advice in reference to the expenditure of votes for the Historic Memorials of Representative Men’, and the government allocated 500 pounds to commence this work.

The committee consisted of the Prime Minister (as chair) as well as the President of the Senate, Speaker of the House of Representatives, Vice President of the Executive Council, Leader of the Opposition, and the Leader of the Opposition in the Senate. (The makeup of the committee is still the same in 2011). One of their early actions was to agree on a list of eminent men whose portraits should be painted, with the first portrait to be that of Sir Henry Parkes, who had died before the Constitution took effect. They also recognised a need for specialist expertise, and quickly established the Commonwealth Art Advisory Board, to provide advice on the selection of suitable artists and to assess the quality of completed portraits.

The CAAB is perhaps better known now for its influential role in the establishment of the National Gallery of Australia, and purchasing artworks that formed the basis of the national collection. But in those early years, the commissioning of portraits for the Historic Memorials Collection was its primary focus, and media reports and other records of the time suggest that these two roles were not distinct, but rather the collection of portraits was, in many minds, considered to be the germ of the national art collection.

After an early flush of activity, two World Wars and the Great Depression intervened and limited the capacity of the Historic Memorials Committee to meet regularly. Constrained finances also affected the rate at which new portraits were commissioned. Despite this, the Collection continued to grow, and portraits of all Governors-General, Chief Justices of the High Court, Prime Ministers, and Presiding Officers of the Parliament have been acquired. In addition to this core group, portraits of other important figures such as reigning monarchs, early explorers, and literary figures were added, as well as paintings depicting special events such as the opening of Parliament in Canberra in 1927, and the opening of the new Parliament House in 1988.

Portraits have also been commissioned or purchased of individuals who in some manner represent a parliamentary ‘first’ such as the first Indigenous Australian elected to Parliament (Neville Bonner), and the first women elected to the House of Representatives and the Senate (Enid Lyons and Dorothy Tangney).

Today, the Historic Memorials Collection includes almost 250 artworks. The majority are portraits, by eminent Australian artists including Tom Roberts, Frederick McCubbin, Julian Ashton, George Lambert, John Longstaff, Max Meldrum, William Dargie, Ivor Hele, Judy Cassab, Clifton Pugh, Bryan Westwood, and Albert Tucker.

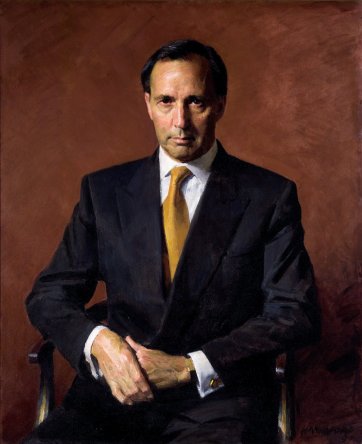

Artists commissioned more recently include Robert Hannaford, Bill Leak, Peter Churcher, Paul Newton, Jiawei Shen, and Rick Amor. Male artists and male subjects are dominant. While the history of the collection itself is not widely known, some of the individual portraits within it are immediately recognised. Better known portraits include William Dargie’s 1954 portrait of Queen Elizabeth II, Ivor Hele’s portrait of Robert Menzies from 1955, Clifton Pugh’s 1972 portrait of Gough Whitlam, and Robert Hannaford’s portrait of Paul Keating from 1997. As well as recording Australia’s political history, the Collection also reveals changes in the history of portraiture in Australia.

Earlier portraits were often sombre in tone and reflected the dignity of the office held by the sitter, borrowing heavily from formal European portraiture. Over time, portraits have tended to become less formal and capture more of the personality of the sitter, sometimes including objects with personal associations, as well as the regalia of office.

The Collection is a valuable and continuing record of the history of politics and portraiture in Australia. Its centenary provides an opportunity to reflect on the way individual political leaders are portrayed, and how they are viewed by the broader community that the Parliament represents.

Empire records

by Kylie Scroope, 1 October 2011

Celebrates the centenary of the first national art collection, the Historic Memorials Collection, housed at Australia's Parliament House.

5 portraits view all

1 King Edward VII, 1910 by George Lambert. 2 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, 1954 by William Dargie. 3 The Hon. Paul J Keating, 1997 by Robert Hannaford. 4 Dame Dorothy Margaret Tangney DBE, 1946 by Archibald Douglas Colquhoun.

Related information

Of Kings and men

Celebrating 100 years of the Historic Memorials Collection

Previous exhibition, 2011This display celebrates 100 years of the Historic Memorials Collection and its role in commissioning portraits of parliamentary and judicial figures in Australia.

Portrait 41, October - November 2011

Magazine

This issue features Kate Beynon, Philosopher Cynthia Freeland, Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu, John Tsiavis & Chris Lilley, UK's BP Portrait Award, Purchasing power in colonial Sydney and more.

The Gallery

Visit us, learn with us, support us or work with us! Here’s a range of information about planning your visit, our history and more!