My interest in portraiture ignited when I was a teenager. Having read a lurid novel about Henry VIII’s wives, I hastened to the history books to find out the truth – and I’ve been seeking to discover it ever since. My initial fascination was with Anne Boleyn, the ultimate historical heroine in the widest romantic sense, and I have never forgotten my first visit to the National Portrait Gallery, London – a treasure house of wonders to an awestruck adolescent – where I came face to face with Anne’s portrait by an unknown artist of the English school, which was painted late in the reign of Anne’s daughter, Elizabeth I. And, having spent several decades since researching Tudor history and portraiture and arriving at a rather less romantic view of Anne Boleyn, I have to confess that I still find that image in the Gallery compelling and evocative. It entrances and it intrigues.

In this year, in which the Gallery has launched an appeal for the restoration of this portrait, it feels appropriate to take a view of it in its historical context. What does it convey to us? Why is it so iconic?

It may not be great art as we understand it today, but it is an important picture. Indeed, it is the definitive portrait of Anne Boleyn, one of the most famous queens in English history. Even though it is only one of several copies of a lost original painted from life between 1533 and 1536, it is the portrait by which most people identify Anne, and it captures the charm and wit of which her contemporaries spoke. It also bears testimony to the famous ‘little neck’ that was so soon to be severed by the executioner’s sword, the eyes that were ‘black and beautiful’ and ‘invited to conversation’, and to her renowned elegance in dress. In short, the portrait, for me and – I know – for many, captures the essence of Anne Boleyn.

Purchased by the National Portrait Gallery, London in 1882 from the Reynolds Galleries, the portrait’s previous provenance is unknown. It dates probably from the late sixteenth century, and was possibly part of a long gallery set of portraits of kings and queens painted for a great house, such sets being popular in Elizabethan and Jacobean England. It is clearly the image of a queen who wanted to make a statement. Our eyes are drawn to her ‘B’ pendant, one of several initial pendants that Anne favoured, which appear in portraits of her and Elizabeth. The painting proclaims her identity, and her sense of her own importance and that of her family. Along with the Latin inscription, which translates as ‘Anne Boleyn, wife of Henry VIII’, it tells us that, despite being of common stock and chosen for love rather than political advantage, this lady has achieved her long sought-after ambition and risen to the highest pinnacle that a woman can hope to attain. There is no hint here of the disaster yet to come.

There are rogue theories that the artist deliberately made Anne resemble Elizabeth, but the proliferation of other versions, as well as an image on a medal struck in 1534 – the only image known to date from the period of Anne’s queenship – strongly suggest that the portrait is an accurate representation of what she actually looked like. And probably Elizabeth did resemble her mother! The multiplicity of this portrait type – at least fourteen versions exist – shows that there was renewed demand for likenesses of Anne Boleyn during the reign of Elizabeth, when Anne’s memory was rehabilitated, a process that began almost as soon as Elizabeth succeeded to the throne in 1558. Anne’s disgrace and execution in 1536 would account for the almost complete dearth of portraits dating from her lifetime; most were probably destroyed, painted over or put away to rot. There have been absurd claims that Anne’s dark hair, cold eyes, pale skin and black dress were contrived to make her look like a frightening wicked witch in her portraits, yet no subject was likely to display such a portrait in the political and cultural climate of Elizabeth’s reign. One contemporary version of the portrait, at Hever Castle, Anne’s family home in Kent, is unusual in that it shows her wearing a filet beneath her French hood (which also features in the version in The Deanery, Ripon, North Yorkshire), and it is the only one of this type to show her hands, holding a red rose. In the Hever portrait, fur cuffs replace the fur oversleeves seen in other versions.

The art of portraiture flourished in England in the early sixteenth century, thanks to the influence of two masters working at court, Lucas Horenbout, who specialised in portrait miniatures, and indeed introduced the form into England, and his exceptional pupil, the great Hans Holbein the Younger, whose portraits give us wonderful insights into a world long gone, and bring to life for us the great and the good of the early Tudor age. Unfortunately, no likeness of Anne Boleyn by Holbein exists.

Prior to this time, English portraiture had developed slowly through the later medieval period, mirroring the growth of realism in art, and there survive just a few early woodpanel images of royalty, some only known through later copies. But with the spread of diplomacy, the culture of the Renaissance and the propaganda of the ‘New Monarchy’ of the Reformation, interest in portraiture escalated. In 1536, Henry VIII, the newly titled Supreme Head of the Church of England, commissioned from Holbein a mural depicting the Tudor dynasty for the Privy Chamber at Whitehall Palace. The mural was lost when the palace burned down in 1698, and is known only through later copies, but a preparatory drawing by Holbein, showing the King in a slightly different pose, survives in the Gallery’s Collection. (The right-hand section of the drawing, showing Elizabeth of York and Jane Seymour, is lost.) The impact of the original mural is evident in the testimony of observers, who felt ‘abashed and annihilated’ on beholding the majestic figure of the King. There was an official impetus to disseminate Holbein’s definitive ‘state’ portrait of Henry VIII, and the number of copies in existence testifies to a high demand, by those wishing to demonstrate their loyalty and approval of the new order, for portraits of the King.

After Holbein’s death in 1543, no other court artist quite lived up to his genius. The latter decades of the sixteenth century saw the emergence of the ‘costume portrait’, a return to the two-dimensional portraiture of earlier decades, but with lavish attention to the details of dress, for the costume of the upper classes was fabulously expensive. This is the portrait as status symbol, not so much an attempt to portray the sitter as a real person, as a blatant advertisement of conspicuous consumption. There was no concept of ‘less is more’ in Tudor times: if you had it, you flaunted it, and the guiding principle was magnificence.

Up until Holbein’s time, most English painted portraits had been of royalty. They were icons of sovereignty. The Tudors had curbed the power of the aristocracy, and Henry VIII encouraged his nobility and courtiers to lavish their wealth on emulating his lifestyle, in order to divert them from spending it on private armies and subversive activities. Holbein’s surviving oeuvre shows the diversity of his commissions, and demonstrates that the portrait had become an essential must-have status symbol for those connected with the court – and able to pay for it. Such commissions may also have been a cover for Holbein’s willingness to spy on those suspected by the government of disaffection from the political and religious status quo that followed the Reformation. In an age long before the invention of photography, portraits had to be representational. That was their primary function. For example, in a period in which royal marriages were made for political advantage, portraits of the prospective partners could serve where a meeting was impossible.

But portraits then had many other purposes. They could project not only an image of a person, but also proclaim to the world how important that personage was. They could be given as gifts, signifying a material acknowledgement of favour and good service well done, or friendship towards a political ally. They were status symbols, proclaiming the wealth, importance and cultural sensitivities of their owners, and as such tell us much about the ego and psychology of the sitters. They were painted to mark great events, or marriage, pregnancy and death. They were just one type of many handsome decorative artefacts in an age in which great houses were designed to impress. Dynasty and display were the watchwords.

Pictures themselves could convey messages: Tudor portraits reveal a whole language of symbolism and allegory, much of which has yet to be decoded. Thus, in the Hever portrait, the red rose held by Anne Boleyn symbolises love, affection, fertility and reverence for the dead. It betokened Anne’s love for Henry VIII, her affection for her daughter, Queen Elizabeth, her fruitfulness in producing that daughter, and the reverence in which her memory was to be held. Such symbolism was implicit in heraldry, mottoes, dress, objects, stance, background, verses, or the ever-popular memento mori; some portraits were painted as emblems of remembrance, such as the biographical portrait of Sir Henry Unton, commissioned by his wife, which combines much of this symbolism with a unique narrative of the subject’s life. A lot can be inferred from ‘reading’ a Tudor portrait.

Today, it might seem that painted portraits have become an anachronism. They no longer need to be representational, since that function has been usurped by photography. Were Anne Boleyn alive today, it would be her photograph we would see, proliferating in every form of media.

But portraiture has been transformed radically with the advent of modern art. Since the end of the nineteenth century, discordant colours, distorted physical features and abstract or surreal settings have become its hallmarks. The painted portrait has had, of necessity, to become more artful, ensuring that its aesthetic appeal never fades.

Today, the portrait reaffirms our faith in icons. Like photography, it mythologises sitters, and yet it can convey so much more. A good artist looks beyond the public face to the character and soul of the subject, and can creatively portray that in an infinite number of ways. As Paul Klee, the Swiss abstract painter, said in 1920, ‘Art does not reproduce the visible: rather, it makes visible’.

Yet surprisingly today’s portraits still have much in common with their Tudor counterparts. Now, as then, portraits – such as that of Paul McCartney by Sam Walsh in the Gallery’s Collection – make you a part of history instantaneously, no matter how influential or superfluous you might be historically. Such images – even surreal ones – crystallise the past and leave it open to interpretation. They can create heroes, even though the truth may not be so heroic. Portraits can also be iconic: they can help to make you the face of a decade, such as the portrait of Blur by Julian Opie, much as Holbein’s image of Henry VIII defined the decade of the Reformation.

Heads of state still commission painted portraits. They are symbols of power that separate the great and the good from ordinary mortals; they are visible evidence that the sitter is sufficiently important for someone to take the time to paint them, and that they are wealthy enough to pay for it. This too harks back to the Tudor age: it is the portrait as status symbol, and it has never gone out of fashion. And portraits of royalty and heads of state still hang in public buildings as expressions of loyalty.

But art is now more egalitarian, and modern portraits can be of anyone: politicians, film stars, writers, rock musicians, scientists, or even one’s own mother on her death bed, which was the subject of the winner of the 2010 BP Portrait Award, Daphne Todd’s Last Portrait of Mother. Even so, they can still feature the kind of symbolism, allegory and trickery that characterised Tudor portraiture.

Why are portraits so endlessly fascinating? It is because they are of people. We are conditioned from birth to be attracted to the human face, and as adults we remember faces better than any other object. We learn so much of others from their faces: expressions and gestures project emotion and are crucially important to how we communicate with and judge each other.

Which brings us to the BP Portrait Award, the world’s most prestigious portrait competition, acknowledged to be the ultimate showcase of the talents of aspiring artists and developments in portraiture, in which many have found success through submitting their work. The quality and diversity of the portraits displayed, the high standard achieved every year, and the exhibition’s popularity with the public are proof that the ancient art of portraiture is alive and kicking still, and that it will flourish for centuries to come.

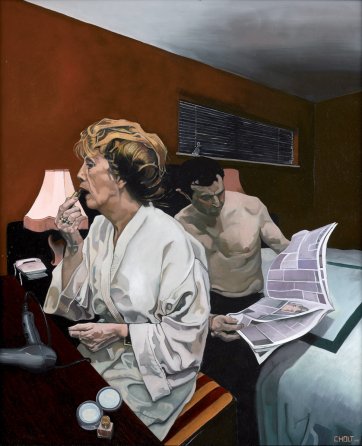

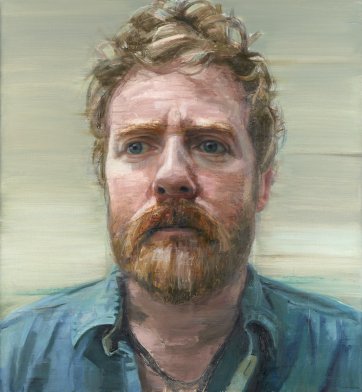

The prize winners for the BP Portrait Award 2011 were announced at the Awards Ceremony on 14 June 2011. The First Prize was awarded to Wim Heldens for Distracted. Icons and Imagery was first published in the BP Portrait Award 2011 catalogue and is reproduced with the kind permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London.

Icons and imagery

by Alison Weir, 1 October 2011

Alison Weir explores the National Portrait Gallery, London and the BP Portrait Award to find what makes a good painted portrait - past and present.

10 portraits view all

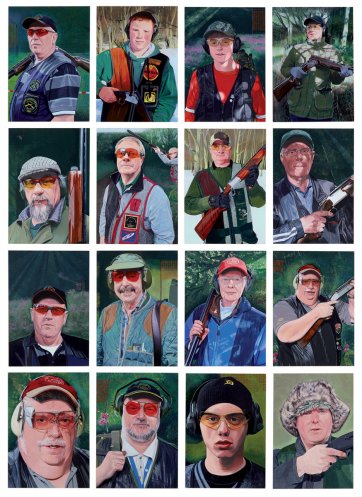

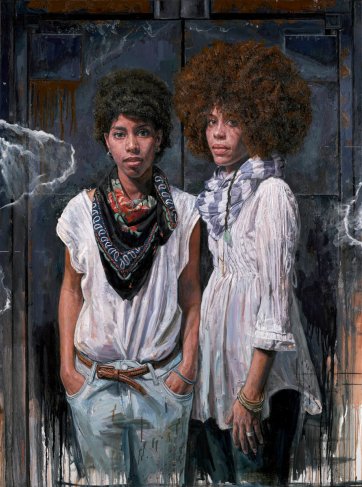

1 Paul McCartney (Mike's Brother), 1964. 2 Anne Boleyn. 3 Henry VIII and Henry VII Hans Holbein the Younger, c.1536-37. 4 The Shooting Gallery - Members of the Batley & District Gun Club. 5 Katherine (and Millie). 6 Little Sister. 7 Venus as a boy. 8 Mo and Kev. 9 Thread the Light (Portrait of Glen Hansard)

.

Related information

Portrait 41, October - November 2011

Magazine

This issue features Kate Beynon, Philosopher Cynthia Freeland, Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu, John Tsiavis & Chris Lilley, UK's BP Portrait Award, Purchasing power in colonial Sydney and more.

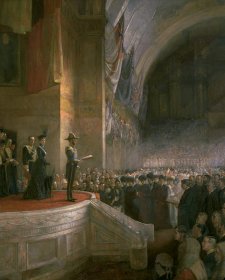

Empire records

Magazine article by Kylie Scroope

Celebrates the centenary of the first national art collection, the Historic Memorials Collection, housed at Australia's Parliament House.

The Gallery

Visit us, learn with us, support us or work with us! Here’s a range of information about planning your visit, our history and more!