The conspicuous desire for social status and advancement of free settlers and ex-convicts alike created the perfect market for colonial portraitists, writes Joanna Gilmour.

Charles Darwin sailed into Sydney in January 1836 and was at first impressed with what he saw. A harbour he considered ‘fine and spacious’ and a town he asserted to be ‘a most magnificent testimony to the power of the British nation’. Sydney in 1836, according to Darwin’s account of it, could be ‘favourably compared to the large suburbs, which stretch out from London and a few other great towns in England; but not even near London or Birmingham is there an appearance of such rapid growth’. The gentleman naturalist accompanying HMS Beagle would later acknowledge his part in this round-the-world surveying voyage as ‘the most important event of my life’ for its bearing on his theory of natural selection. The Beagle spent two months on and around the Australian coast, during which time the thought first occurred to Darwin that species might be shaped to fit their environments. But while encounters with creatures as weird as the platypus may have prompted him to muse on a different model of creation, Darwin’s observations of Sydney society ultimately created the conclusion that the colony’s charms – the villas and cottages ‘scattered along the beach’, the streets that were ‘regular, broad, clean and kept in excellent in order’ – were skin deep. Sydney no doubt displayed a remarkable rate of progress. But it was a place peopled in part by the flashy, venal breeds best adapted to mutable social distinctions and rampant growth and those whose dodgy or lowly origins were easily concealed behind a veneer of fashion and possession.

‘On the whole’, Darwin tells us, ‘I was disappointed in the state of society. Among those, who from their station in life ought to be the best, many live in such open profligacy that respectable people cannot associate with them. There is much jealousy between the children of the rich emancipist and the free settlers; the former being pleased to consider honest men as interlopers. The whole population, poor and rich, are bent on acquiring wealth.’

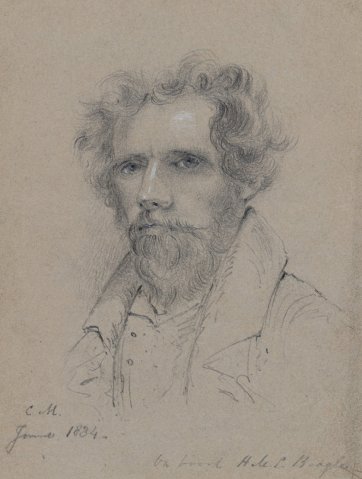

Darwin was one of a number of observers who curdled at the colonists’ conspicuous consumption and who, like others blinkered by distaste for Sydney’s social anatomy, determined that ‘nothing but rather sharp necessity should compel me to emigrate’. The colony’s intellectual life was likewise invisible to Darwin, despite his visit here occurring at a time when high-pitched prosperity and confidence were creating a febrile market for artists and others who saw opportunity for advancement in a community blended as Sydney’s was: from free settler and ex-convict; sterling and ‘currency’; the well-born and the self-made. Darwin’s friend and Beagle shipmate, Conrad Martens, was among those whose arrival in the colony was thus fortuitously timed.

Martens (1801–1878) is often thought of as the first professional artist to choose to make Australia his permanent home. The Londontrained landscape painter joined the Beagle in Montevideo when the man who had started out as the voyage’s official artist, Augustus Earle, was forced to quit through ill health. In Valparaiso in October 1834, a year after joining the expedition and two years before its completion, Martens was required to leave the Beagle due to lack of space. He then made his way to Sydney via Tahiti and New Zealand, arriving in April 1835 with a letter of introduction to the Beagle’s one-time commander, Phillip Parker King. It was through associates like King, the son of a former governor of New South Wales, that Martens made the sort of social connections that soon scored him commissions from those who considered themselves the colonial elite. In addition to the numerous drawings and ‘views’ he made of Sydney Harbour and of features and landscapes around New South Wales, Martens was engaged by many landowners to create portraits of their estates and of the stylish villas with which their holdings were ornamented.

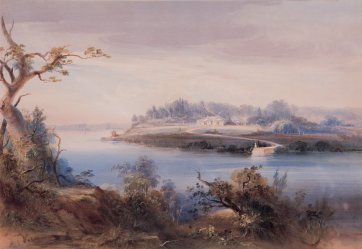

Among some of the best-known works by Martens in this genre are his paintings of harbourside homes like Rosebank, owned when Martens depicted it in 1840 by the merchant, Robert Campbell; Craigend, the Darlinghurst mansion built for surveyorgeneral Thomas Mitchell; and colonial secretary Alexander Macleay’s Elizabeth Bay House (‘the finest house in the colony’). Though argued to have, through the company of Darwin and other scientists on the Beagle voyage, added a topographical and objective edge to his style, it was seemingly Martens’ dexterity in the romantic and picturesque mode that served him best in New South Wales. An ability to elicit moods of grace and plenty from a land Darwin had characterised as gauche and often wearing a sterile, ‘uninviting aspect’ was precisely the skill required by clients who commissioned art as a way of making sense of their disconcerting surroundings, or of neutralising some of the more odious elements inherent in colonial life. In this, the harbour and estate scenes produced by Martens are akin to the output of portraitists practicing in Sydney in this period.

Prior to the 1830s, the Sydney market for portraiture was narrow and cornered by a handful of artists. Richard Read, banished to Sydney for forgery in 1813, enjoyed some success as a portrait and miniature painter through the help of patrons like Governor Macquarie. Read’s son, also Richard, arrived in Sydney in 1819. Signing himself ‘Richard Read junior’ to distinguish himself from his father, he too created portraits for a number of prominent families. Charles Rodius (1802–1860), who arrived in 1829, was another convict who became a sought-after portraitist as a free man; while artists such as William Nicholas (1809–1854) chose emigration to Australia for its prospects of success. Colonists also took advantage of Augustus Earle’s time in Australia between 1825 and 1828. Like Martens, Earle is significant for the topographical and documentary images he created in the course of various excursions, but is notable too for the portraits he produced in Van Diemen’s Land and New South Wales. These included the first large-scale oil portraits painted in the colony: such as his two-metre tall 1826 portrait of governor Thomas Brisbane; the equally statuesque portrait of the military officer and government official, John Piper; and that of Piper’s wife, Mary Ann, with four of their children. Mary Ann, a teenager when she and Piper met, was a convict’s daughter who’d borne the first of numerous children before she and Piper were married in 1816. Earle’s portraits of the family might therefore be considered exemplary in the use of art to divert attention from one’s anomalous social position.

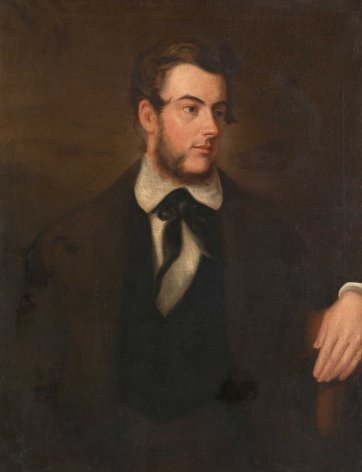

It would seem then that the colonial art world, like the society that fed it, was one to which the enterprising and judicious practitioner – or the provincial artisan-style of artist who, as historian Richard Neville has put it, ‘saw themselves, or was seen to be, on the outside of high art practice’ – was better adapted. Martens’ friend, Maurice Felton (1803–1842), was someone who occupied this category: an artist whose skill and training, though not top-notch, was sufficient for success in a colonial market and whose Sydney career thereby resulted in some fine and telling examples of early Australian portraiture.

A Leicestershire machinemaker’s son, Felton was outside of high art practice enough for painting to be his sideline and it was as a doctor that he made a living before coming to Sydney. A Felton family historian has speculated that Felton’s gamble on emigration was, like that of countless others, taken on the chance of its yielding financial security for himself and several dependants – his wife, sisterin- law, four children and two unmarried sisters – all of whom came to Australia with him. Presumably without sufficient means to pay the passage, Felton worked his way to Australia as the surgeon superintendent on board an immigrant ship called the Royal Admiral, which arrived in Sydney in September 1839.

Although listed in July the following year as one of the ‘duly qualified medical practitioners in this colony’, Felton was apparently having more joy as a painter. Within a few months of his arrival, The Australian was applauding the ‘specimens’ of his portraits on exhibition at a George Street business, declaring that ‘for faithfulness of likeness and brilliancy of execution, they rival the productions of many of our best artists at home’. These same specimens attracted the attention of Alexander Brodie Spark, a merchant and arts patron who a couple of years earlier had commissioned from Martens a depiction of his Cooks River seat, Tempe House. Spark’s diary entry for February 8th 1840 notes a visit to ‘Mr Felton’s’ and that ‘I was much pleased with his portraits and various sketches’. In April the same year, Spark issued to Felton the first of several invitations to Tempe; and in May – ‘desirous of having my loving bride’s likeness’ – commissioned him to create a portrait of his wife, Frances Maria. Painted, so Spark’s diary reveals, in the course of several sittings at the artist’s home between May and August 1840, Felton’s portrait of Frances Maria Spark is stately and splendid, demonstrating her social rank and confirming the technical skill and showy sensibility that lent Felton’s work so effortlessly to the requirements of colonial clients.

Felton’s subjects, though from a mix of spheres and origins, largely shared the supposed taint of commercial motivations and the experience of finding in colonial life and enterprise a high degree of wealth or social profile. Spark, a free settler who came to Australia in 1823, made a fortune in New South Wales with business ventures that included shipping, banking and wool exporting. Before succumbing to the depression of the 1840s, Spark had found in architecture and the arts an outlet for his wealth, commissioning local artists like Felton and Martens, purchasing European paintings for his collection and later supporting the Society for the Promotion of Fine Arts. In addition to the grand portrait of his wife, Spark commissioned his own likeness from Felton, his diary recording a number of hour-long sessions with the artist in September 1840. That same month, the Sydney Herald was announcing its approval of Felton’s portrait of Queen Victoria – a copy of that painted by the American artist, Thomas Sully, and one of two paintings of the monarch that Felton made. From this time and throughout 1841, Felton completed most of the known portraits bearing his backof- the-canvas inscription: ‘painted by Maurice Felton, Surgeon, Sydney.’ These include his portrait of Anna Elizabeth Walker, the wife of landowner Thomas Walker and a member of the prominent Blaxland family of graziers; his portrait of Martens; of the Sydney draper, Thomas Chapman with his nephew, Robert Cooper Tertius; of the landowner of ex-convict parentage, John Tindale and his wife, Mary; and the self portrait – advertised in 1849 as ‘evidently the product of no mean artist’ – that confirms his flamboyant style. Felton’s speciality in oil on canvas made his portraits distinctly more desirable as symbols of position and thus pitch perfect for parvenu clients or those needing assurance of status. This appeal is amply demonstrated also in another of Felton’s 1840 portraits – that of Frances Samuel, a young woman whose emigration eight years earlier had been financed by two spectacularly successful businessman uncles, one of whom, Samuel Lyons, had been transported to Sydney in 1814 for pick-pocketing a handkerchief.

In their ornate gold frames (some supplied by Felton’s brotherin- law, Solomon Lewis) and in his attentive rendering of fabrics, fashions and jewellery resides proof of the aspirations, pretensions or vulgarities of Felton’s sitters. Felton’s paintings are evidence too of the rude prosperity (‘it appears that a man of business can hardly fail to make a large fortune’, Darwin opined) and consumerism witnessed during Felton’s time in Sydney by people such as the writer, Louisa Anne Meredith. Sydney society, by her measure, was witless and gauche, populated by those who ‘pay more attention to the adornment of their heads without than within’, the women exhibiting ‘an utter absence of interest or enquiry beyond the merest gossip – the cut of a sleeve, or the guests at a late party ... But all are dressed in the latest known fashion, and in the best materials.’ Within two years of his arrival, Felton’s work as an artist had garnered high regard and, in contradiction of the bleak picture painted by some, was being described in tones that signified enthusiasm and not distaste for Sydney's character and prospects.

The Sydney Herald, for example, recorded in November 1841 that various ‘connoisseurs’ (among them Spark, and governor George Gipps and his wife) had ‘honoured Mr Felton, the artist, with a visit to his collection of oil paintings’ and ‘expressed their high gratification and admiration of his talents’. The same editors later declared ‘that we felt a pleasure in looking in these specimens of Fine Arts we did not anticipate’. Felton’s work – his portraits of ‘well-known individuals’ and ‘numerous views in the vicinity of Sydney and in the Illawarra’ – signalled, by this estimation, that ‘the day was not far distant when we should no longer be characterised as a mere money-getting and money-loving people; but that we should become conspicuous for the ... cultivation of those arts that at once improve the heart and mind.’

Felton’s contribution to the emerging local art world, though well received, was nevertheless short-lived. In a melancholy twist, the exhibition so favourably reviewed in October and November 1841 was in fact a lottery conducted by Felton where, for one pound, subscribers purchased the chance of possessing the portrait of the Queen or another example of ‘Mr Felton’s talents in the delightful art of painting’.

Spark’s diary hints, however, that Felton – an artist but ever the surgeon – knew by this time that he was dying, making the exhibition hitherto blithely described as Australia’s first art union possibly the means by which Felton made a final attempt to provide for the family he had relocated to Australia. He died in Sydney several months later, in March 1840, ‘deeply regretted by all who had the pleasure of his acquaintance’. Though as regrettably somewhat small in number, surviving examples of the works created during Maurice Felton’s too-short Sydney career remain in a select number of Australian collections, providing a rare and vivid portrait of how people saw themselves at a thriving, distant time.