How does a philosopher’s view of portraiture differ from that of an art historian?

An art historian would be more likely to focus on issues of technique and style in portraiture, as well as on the context in which artists work, their influences and traditions, patronage, and so on. Certainly, some art historians have broad interests and ask more general questions such as what is the function of portraiture or whether portraits can capture the ‘truth’ about a subject, but that’s more unusual. Philosophers tend to ask different questions, sometimes odd ones, as with Descartes’ famous question about how you could know whether the people around you are real or merely automata. I am interested in broad questions about how to define portraits, how the mind and body are related in visible ways and whether there is such a thing as ‘subjectification’ in art. Philosophers ask whether there can be a portrait of a hurricane (after all, they have names) or of a fictional person like Sherlock Holmes. One of the aims of Portraits and persons (2010) is to look at portraits to find information about how to define or describe what people are. I was struck when researching the book to realise that philosophers have looked more to novels and biographies rather than to visual art to gather data about how we have defined ourselves over time.

The English writer and lexicographer Samuel Johnson said, ‘I would rather see the portrait of a dog that I know, than all the allegorical paintings they can show me in the world’. Johnson clearly thought that portraits have the power to engage with the average person and that it is possible to make a portrait of an animal. What is it that makes a portrait so interesting and can a picture of an animal ever genuinely be a portrait?

I like that remark, I hadn’t heard it before. My view is that we all find portraits interesting because as a species humans have evolved to be highly social animals that are attuned to others around us. We attend to cues about whether people are friendly or angry, and we have inbuilt capacities to recognise and remember faces—amazingly many of them, in fact. Portraits help us to get to know and remember people, and they stand in for people who are absent or lost to us. The earliest function of portraits was to memorialise the dead. Of course, human beings often have pets and animals around us that we love, so it isn’t surprising that we care a lot about pictures of the animals that we can recognise as individuals (personally, I take thousands of photos of my cats). Portraits and persons argues that pictures of animals meet two of the three criteria for portraits: they can show recognisable individuals with inner lives. However, I don’t believe that they meet the third criteria: animals do not pose in the sense of presenting a self to the outside world as we learn to do from a very early age. Animals do not understand the nature of art – after all, other animals don’t make or use images.

You have suggested that a psychological awareness and an indication of an inner life is central to a portrait – how is this represented? Are we really able to represent the inner life of a person?

That’s a hard question and in a way it’s the central philosophical question about portraiture. It’s as if the portrait artist manages a conjuring trick, making inert materials almost magically appear to come alive. To explain how this can be done, I think the prior question is how real flesh-and-blood persons reveal their inner lives to each other. This takes us back to Descartes’ mind/body problem: How do I know that you are a real person, not a machine or robot? How do you reveal your inner life? How do we ever recognise the moods and emotions of other people? Well, the fact is, it’s really not so difficult, since we actually have evolved to be able to do this.

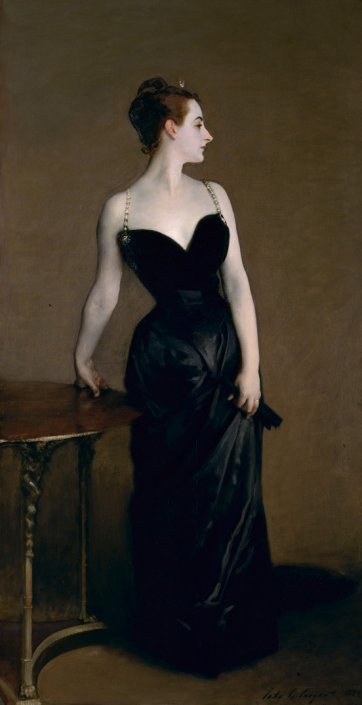

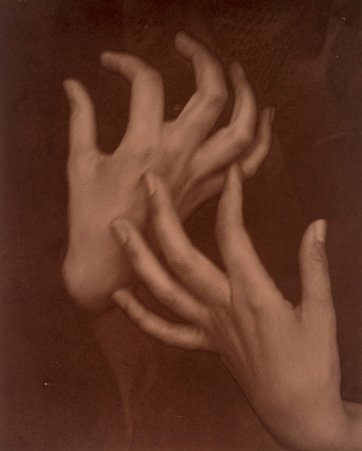

We read many cues from a person’s facial expressions and bodily stance and, of course, settings always help too. A person might look furious, but if we realise they have just been exercising, then we relax because we realise that the look on their face shows exertion and not anger. Over generations of training and in changing social contexts, artists have developed techniques to show some of these things, such as the facial expression of emotion, by changing small aspects of works showing people’s eyebrows, eyes, mouths, and so on. And of course in most cases portraits have also shown a person’s body and placed that body in a setting. So if we see someone like Sargent’s Madame X in a fine, revealing gown with a dramatic pose and turned-up nose, we ‘read’ her as showing confident awareness of her own beauty and distinctiveness. Whereas when we see Velázquez’s Pope Innocent X, we recognise that here is someone very powerful and arrogant, in part, due to the throne on which he is seated and also his rich scarlet robes trimmed with frothy lace, long lean head with a hawklike nose and the way in which his hands appear elegant yet also scary and claw-like.

Didier Maleuvre, Professor of French and Comparative Literature, University of California, spoke at the National Portrait Gallery recently and suggested that ‘the aura of a person’ is vital to a portrait and this derives from the encounter; the time spent by the artist with the sitter somehow allows inner life to be revealed and recorded. Does this rule out a posthumous portrait as a valid portrait? Can only an artist do this? Can a machine made photograph, which is an encounter of only an instant, record this aura?

It is unfair to compare photographs to paintings in this way because there are many great portrait artists in the medium of photography. The photographer, not the camera, makes the picture. Look at Alfred Stieglitz’s series of photographs of his wife Georgia O’Keeffe, taken over time and showing her in so many poses and moods, sometimes focusing only on her hands, face, or breasts – the entire series becomes the portrait. On the one hand, there are many features of the medium of photography that require artistic choices, such as the kind of camera, lens, framing, background, shot selection and printing. And a portrait photographer often interacts with his or her subject while they are in the studio, too. On the other hand, there is some possibility that a person can get lucky using a camera and capture an especially telling image of a person without putting a lot of work into it. That’s not going to happen for a painter. I would say in such a case that the person might be someone who simply projects a strong aura, in the sense that they have an especially expressive face or vivid personality, and that the photograph happens to capture this. Concerning posthumous portraits, I suppose that if the artist knew someone and portrayed that person later, it might still be quite successful as a portrait. Otherwise, if we are depicting someone like Cleopatra, say, then it’s simply a question of whether this is convincing as a likely version of who she may have been, but no one can really say.

You have mentioned that you believe that one of the qualities that a portrait must have is the sitter’s awareness of being placed in a portrait. If you believe that the interaction between portraitist and sitter is vital so that the sitter is conscious of posing then self presentation is very important. For this reason I understand that you have reservations about candid photographs being genuine portraits. What about when the sitter doesn’t like the way the self has been recorded – does this make the portrait less valid? I am thinking of portraits rejected by the sitter, for example, when the Graham Sutherland’s portrait of Sir Winston Churchill was destroyed because it displeased Churchill and his wife.

The portrait may have been rejected because the artist saw aspects of Churchill that were actually there but that he did not like to acknowledge. This is partly why so many artists chafed at having to do portraits to make a living, because they did not like to subject their own vision to the subject’s need to be flattered. Also, the circumstances of exhibition can affect the response, as with Sargent’s controversial portrait of Madame X (Mme Pierre Gautreau). She was apparently happy with the depiction up until it was shown in public and then it became a scandal and then she rejected it. Isn’t one of the reasons for valuing a particular artists’ portraits that they can show the truth about a person even when that might not seem acceptable? It’s a fact of life that we are not always in control of how we are seen by others.

How does a portrait differ from a self portrait from a philosopher’s perspective? Is a self portrait necessarily better for a longer ‘encounter’ and being more intimate?

No, I don’t think self portraits are necessarily better, because there is such a thing as self deception! We may not be very good at seeing the truth about ourselves and probably everybody wishes to present a more attractive than true image to the outside world. That’s why I am particularly interested in the artists who did multiple images of themselves over a period of years – Rembrandt, Cézanne, and Frida Kahlo. They worked at it in order to develop more honesty in showing themselves. Philosophically, this is like the distinction between biography and autobiography. Each genre is of interest, but we can’t always take the autobiography to be the gospel truth. Artists who have acute insight into other people may not necessarily be insightful about themselves, because that takes a certain attitude of detachment that is hard to achieve.

Clearly a figure in the landscape can be a portrait, but is there a point when the landscape becomes more important and the work ceases to be a portrait?

That’s an interesting question, especially when you think back to particular periods in which the landscape such as a country estate, complete with trees, fields, a big house, animals, and so on, would be part of the setting that would establish that a married couple in the foreground were socially prominent landowners. I can imagine a landscape being important in a portrait of someone who was a naturalist, say, or a fisherman or farmer. But yes, if the landscape is the fundamental focus of the image and there is little sense of the inner life of the person who is more or less dwarfed by it, I would agree it ceases to be a portrait.

Portraiture is still important to society and artists still make portraits. Have you a favourite portraitist?

Goya, though I am not sure I would want him to paint me because he could be a bit wicked in his depictions. Among living artists, I would pick David Hockney. I admire his somewhat cool but insightful images of the people he paints. He uses space and settings especially well in hinting at human emotions and relationships, and I love his use of vivid colours. He has also done marvellous experiments with fractured or collaged images, especially in depicting his mother.