On a hillside on the shores of Loch Alvie in the Scottish highlands below heathercovered slopes sits a little Presbyterian church. In the churchyard under a large moss-covered gravestone lie Donald Robertson and Christina McBean. The carved inscriptions, still legible despite the heavy weathering, tell that Donald was a farmer in nearby Dunachton who died in 1828 aged seventy-one and Christina, his wife, was forty when she died in 1812. They had ten children, two of whom died in childhood. Of the eight surviving children five migrated to Australia over a period of ten years. The youngest to emigrate was Christian, born two years before his mother died. The first to arrive in Australia were Donald’s second and third eldest sons, John and William, and it is William that this article is largely about.

Attracted by the generous land allocations offered to settlers with experience and capital by the Colonial Office, they embarked on the Regalia for the long voyage to Van Dieman’s Land, arriving in late December 1822. Neither saw their father again, but they selected land near Hobart and the farming skills that they had learned from him were instrumental in their subsequent success. Blessed with a fierce entrepreneurial spirit, in 1832 William set up the Hobart business, Robertson Brothers, with John and their younger siblings James and Daniel, who had emigrated and settled in Launceston. Robertson Brothers brought the finest haberdashery, crockery and silverware to the tiny colony, no doubt influenced by the tastes of the elegant Margaret Whyte whom William married in 1834. Farming was still in their blood, and William and John were influential in setting up the Port Phillip Association which was established to explore and open up new grazing land around Port Phillip Bay. John Batman led the first expedition and soon after he had struck a deal with the local aboriginal tribes around the ‘place for a village’ that ultimately became Melbourne, William made the hazardous Bass Strait crossing to see the land for himself. And hazardous it was. On his second trip William's ship was blown off course by a gale. His party landed at Western Port Bay and they were left to walk the eighty kilometres overland to their destination, the fledgling village on the banks of the Yarra River.

History relates that the huge tracts of land that William and John were allocated on the western shores of Port Phillip Bay in return for their role in financing Batman’s expeditions were unable to be taken up. The Governor in Sydney disallowed the Association’s allocations and instigated new land sales. Not one to be short-changed, William established an early foothold with land he purchased near what is now Sunbury, and by the early 1840s he had taken up land around Lake Colac. William was recognised as one of the leading pastoralists of the colony and by the 1860s had built The Hill, a splendid mansion overlooking the lake. His herd of 10 000 Durham and Hereford cattle was one of the finest in Australia.

In common with many of the other successful colonialists in Hobart, William Robertson patronised several of the early local artists to record his family and decorate his home in portraits, pastels, landscape paintings and early photographs. He commissioned several portraits and sketches from the artist Thomas Bock, including ones of his brother John, himself, his wife Margaret and their daughter Jessie who died aged fourteen in 1849 which are regarded as among Bock’s finest works. Bock was possibly instrumental in the production of some beautiful Daguerreotypes of several family members which date from the same period, and in several other works. William Robertson closed Robertson Brothers in 1852 and moved to Victoria. Here he expanded his pastoral activities and continued to be influential in colonial affairs. He hosted a controversial visit by the Duke of Edinburgh, the Queen’s second son Prince Alfred, at The Hill in 1868 – controversial because, in their haste to reach The Hill and enjoy the hospitality, the Duke and his party had ridden straight through the centre of Colac without stopping, covering the assembled dignitaries, patriotic citizens and flag-waving school children with dust.

William was seventy-six when died in 1874 following an accident with his horse and buggy. By this time, though, a new Robertson Brothers had emerged at Colac. William’s four sons, John, William, George and James, who each had taken over a portion of The Hill, were partners in the enterprise jointly, although James was the one who took on the role of managing director. They had enjoyed a privileged life far removed from the rigors of the hardy up-bringing and limited opportunities that had forced their father to leave Scotland. Each received the best education possible, with William graduating in law after a gentlemanly sojourn at Oxford.

After his father’s death, William stayed on in The Hill, while his three brothers moved into their own equally grand homes on their properties. He married Martha Murphy, a daughter of JR Murphy, another prominent Victorian settler. William became involved in colonial Victorian politics and represented the local Colac constituency in both the Legislative Assembly and the Legislative Council for many years from 1871. Despite their prominence and early pastoral successes, Robertson Brothers ended in the closing days of the century. A rural downturn and a mistimed move of their cattle interests to Queensland, compounded by James’ early death in 1890 and William’s in 1892, led to the partnership being dissolved and most of the land and stock sold off.

However, there are significant artistic legacies from this period. Like his father, William was interested in both art and imagery and was a capable artist himself. He commissioned a set of family portraits from Robert Dowling in about 1885. These depict his father, painted posthumously from a photograph, himself, and his eldest daughter, Elise Christian Margaret, known as Dolly. The portrait of Dolly is a large canvas with a fascinating history of intrigue, neglect and finally rescue and recognition, but that’s another story.

William also became fascinated by photography, especially when it became easier for an amateur to practice the art. Using the bulky and cumbersome equipment of the day, he began to take photographs in the late 1860s and process the plates himself. His albums remain rare examples of their type, capturing lovely photographs of a privileged family life in those distant days, including his father in a top hat in front of the family mansion, The Hill. So, while Donald and Christina rest for eternity in the tranquil surroundings of Loch Alvie in Scotland, we can thank them for this lasting artistic legacy in paintings and photographs left to us by their son William and his Australian descendents.

Brothers on farms

by Malcolm Robertson, 1 October 2011

Malcolm Robertson tells the family history of one of Australia's earliest patrons of the arts, his Scottish born great great great grandfather, William Robertson.

10 portraits view all

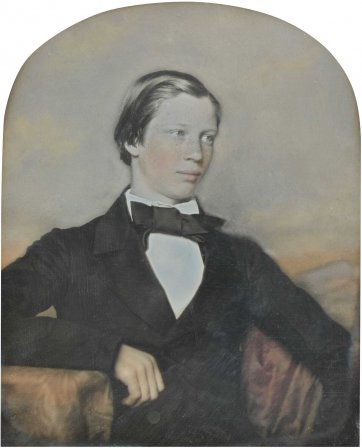

1 Margaret Robertson, c. 1855 an unknown artist. 2 William Robertson, c. 1852 an unknown artist. 3 William Robertson jnr, c. 1852 an unknown artist. 4 William Robertson, 1850.

Related information

Elegance in exile

Portrait drawings from colonial Australia

Previous exhibition, 2012Elegance in exile is an exhibition surveying the work of Richard Read senior, Thomas Bock, Thomas Griffiths Wainewright and Charles Rodius: four artists who, though exiled to Australia as convicts, created many of the most significant and elegant portraits of the colonial period.

Portrait 41, October - November 2011

Magazine

This issue features Kate Beynon, Philosopher Cynthia Freeland, Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu, John Tsiavis & Chris Lilley, UK's BP Portrait Award, Purchasing power in colonial Sydney and more.

Essential portraiture

Magazine article by Michael Desmond

Michael Desmond in conversation with University of Houston professor of philosophy Cynthia Freeland.