I first saw Kitty Kantilla's work in the Art Gallery of New South Wales in the earty 1990s, soon after I had returned from ten years living, working and studying art in Europe. I became intensely interested in her, and after trying every possible avenue to find out more about her and her work I tried to get a visa to visit her community on Melville Island. I had no intention of painting a portrait. My initial idea was to interview or talk with Kantilla about her life for a book I was researching on Australian women artists of a certain generation as mothers and mentors to women artists of a younger generation.

My requests were repeatedly discouraged by administrators and my letters, and my phone calls went unanswered, so in June 2001 I flew to Darwin determined to obtain a visa to visit the island and Jilamara Arts Centre from the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Land Council. I succeeded and flew to Milikapiti (Snake Bay) on Melville Island. Although Jilamara was locked up I went exploring and soon encountered some local women and children peacefully sitting in the morning sun on the oval. We sat together chatting, I told them I was an artist and I showed them my sketch book, asking if I could draw. I found them extremely receptive and entertained by my ability to do quick likenesses and representational portraits of themselves, their babies, and even their dogs.

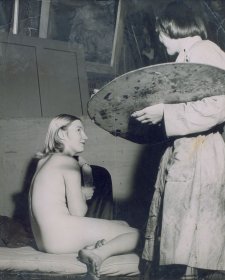

Gradually the women artists returned to Jilamara and Kitty Kantilla arrived, but she warned me to go away and leave her alone, saying she didn't want to 'give her stories away'. I tried to reassure her that I did not intend to persecute her and had the greatest respect for her privacy. Pedro [Kitty's nephew] introduced me to Kitty's friend and rival Freda Warlapinni who invited me to watch her paint for some time. We exchanged questions about materials and working methods and watched each other draw, she showed me where and how pigments were sourced and ground and then mixed with natural binders or PVA glue to the required painting consistency.

Later Freda asked to see my sketch book, she then wanted to see my likeness of her, and perched atop a table for me to sketch her.

As I watched and drew at Jilamara with the two elder Tiwi women, I started to learn a little about their natures, their movements, relationships, and physicality. Their faces appeared like skin maps, containing a history of their lives experience - joy, sadness, hardship and achievement and a great depth and knowledge of a land and its people, so far removed from the city and gallery where their work first attracted my interest. Kitty Kantilla had not wished to be interviewed and 'give her stories away' but had instead, with great wisdom, given me an insight into what I had been searching for; through 'seeing' rather than 'telling' she had allowed me an understanding of herself and her work. It was an invaluable lesson in the importance of knowledge acquired through artistic process and practice.

The portrait painting 'Kitty and Freda —Milikapiti' then began to germinate over the next two years, during which I tried many times to paint versions of my drawings and experiences with the two Tiwi artists, but threw the attempts away. I wanted to convey not only the immediate 'foreignness', the distinctive 'sense' of the Milikapiti community, the life in the light and dust of the environment, but also the sense of history of the Tiwi culture, the traditional skin painting of the women, the Pukumani ceremonies, the relationship to land and death and the instinctive application, yet studied learning of mark making of the artists. I wished to capture my great respect for these two artists, as women of their time; their resilience and independence, their strength of character, their defiance in the face of any intrusion in their lives, their fiercely proud and protective instincts, their unity with their culture and traditions and their extraordinary artistic ability. The painting needed to communicate something of the spirit of these women, which I had been allowed to glimpse and which is so magnificently contained in their paintings, carvings and drawings. I knew that the portrait would only succeed if it could convey something intimate, something of what the women had so graciously shown me, that small insight into their lives. At the same time, there was the dichotomy of a painting of two women elders of the Tiwi art community, fierce, native 'warriors', Kitty the indomitable matriarch and Freda her frail 'spider like' crony, who were also artists, contributing to a Western market. The lesson that Kitty had taught me, about the importance of perception and of personal experience to any 'real' understanding was invaluable.

The painting was a long lesson in trust and confidence, although it was eventually completed, instinctively, in a single night. Sadly Kitty Kantilla died a few days after it was hung in the Portia Geach Prize of 2003 and the painting had to be withdrawn from view for a while. Just a few months later, her rival and ally Freda Wartapinni died.