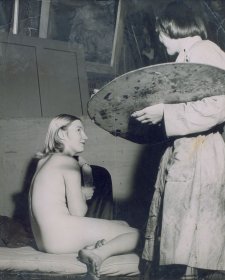

'The shock happens the first time. You feel this must be a dream, the kind you cannot wake from. This is really me - sitting here without a stitch of clothing on, naked, motherless nude, starkers - up on a dais in front of a room full of unknown people. It is real. It is true.

What would the neighbours say, your dear old grandmamma...'Shocking, shocking!' Then you become real. You are no ordinary undressed damsel. You are a statue in flesh and bone, a landscape in anatomical form, a still life in living state, a traditional life class model.'

'So, artist's model, I sit here in birthday suit, in angel suit. I sit here as anonymous as on an operating theatre table. Only my shape matters, my solidity, my corporeal substance disposed in structure of limb and torso, head and haunch.

Barbara Blackman was in her early twenties when she modeled her 'nice Swedish skin' and her 'athletically round body' at the Gallery School, Melbourne.

Barbara spent a great deal of those years naked -life modelling sometimes as often as six days and five nights a week. Wife and muse to artist Charles Blackman, Barbara was, throughout the 1950s steadily losing her sight.

In her autobiography Glass after Glass, Barbara recalls, with her customary verve, the experience of life modeling.

'When I took up modelling full time in Melbourne, I was no novice. I had come to enjoy the role. It suited my independent spirit. I posed, I got paid. I honed my love of solitude into a skill of still performance. I had meditation thrust upon me and sat contorted into what I later recognised as yoga poses. I listened to the master of each class as he went from board to board, drawing each student towards his own way of handling pencil, charcoal stick, conte crayon or paint-dipped brush. I learned to draft my pose to fit the purpose of the method. I took a craftsman's pride in arranging the pose to suit the class, holding it for long periods without moving more than a breath, or repositioning into quick-change poses like stills of a movement. I kept a coded notebook in which I planned my repertoire on standing, reclining, sitting on stool, on chair, on tussock, on mat, my backs, fronts, sides, always the different planes of ankles, knees, hips, ribs, wrists, elbows, shoulders, head, the planes inclined, counterpointed, reciprocated. I was left alone to use my imagination... I was making my own mud map of this territory of the 'art world" to which I had been given in marriage. I found my own niche in that exciting world of Melbourne art in the Fifties.

'Gallery school had tradition. Students spent a couple of years there studying painting under professional painters with the intention to become one themselves. The gallery itself opened at ten o'clock, classes began at the gentlefolk hour of quarter past ten. I came in through the revolving door at the main entrance, had a word to the familiar guards who also spent their days in silent pose. Past the screens of Blake etchings, a different one peered at each morning, then out through the 'No Entry' to the marble staircase to the studios above...

'The first Monday morning was spent in setting up the pose for the ensuing fortnight... The walls were impasto with a random dung patina of wiped-down brushes and thick with paintings by students of the last hundred years. Three banks of eyes watched -the portraits from the wall, the students at their canvasses, I from my fixed point. I looked also in to the past of childhood remembered, the present of shopping list and possible weekend party guests, a future of great paintings, coming not from these before me, rather from a secret painter left behind at home in the coach-house loft, painting twelve hours a day but one of no school, he who was referred to as 'Mrs Blackman's husband'.

The master painters - William Dargie, Roland Wakelin, Alan Sumner and Murray Griffin - had their own studios further along the passage from which they emerged periodically to tutor their students in Still Life or Life studies in the way of a doctor perusing his ward of patients - paintings in states of emergency treatment, steady progress or revival tactics... In winter I sat between two heaters -and that burning curiosity for life that stirs my blood kept my inner being also warm.

The model is an enigma to those outside the art world. On visits home to Brisbane my occupation was never mentioned, and archived letters of the time have no reference to it Others saw it as bread-winning casual labour, but nothing like an art-form in itself. Within a year I decided the five shillings an hour pay should increase and, for the first time, used the press for my purpose. The photographer leapt to the bait, in for the kill of a nude pictorial. I grasped the blanket around my shoulders and refused to smile for the dickie bird, saying 'This is not a smiling matter'. The photograph story came out 'Bare wage for a Bare Model'. The hourly rate went up.

'Husband Charles never drew me as posed nude. In the late Fifties he was invited to contribute to an exhibition of nude work. He asked if a drawing of a baby without clothes was eligible.

'The intimacy of the life class is sacrosanct. I had the reputation of being remote, the ice maiden's daughter, the intellectual, often because I was unable to meet the gaze of another. My sight lack kept me distant. I was the model for whom the artist's work held no interest but for whom the right to do his best was my raison d'etre. In fact the good model does speak to the class. She speaks in a silence of eternal form. She depersonalizes her body to allow it to be personalized by the painter. She becomes one with all those patient unknown women who sat before painters and became Madonnas, Venuses, Madame Olympies. They transcended name and identity and transformed into images in art. They offered their present moment to the gaze of the painter who transfigured it, in the light of his past and the presence of his love for his work, into a metaphor that passed on to the future. The model is integral to the painter's understanding of his art. She is the focus of the student class, the portfolio of the mysteries of form. Her own content is her own secret. The body is the noun, her self is the verb, the adjectives all the painter's. The model has in her power the leveling of the spirit of those who draw her. to heights or depths. Yet it leaves her unpossessed, free to her own thoughts, private in her teeming solitude'.