Canadians chronically worry over this question of our national identity - it has been said that this worry is the most prominent characteristic of our national identity.

But its unique place in our psyche is epitomized by the fact that the word 'national' does not appear in the name of the Portrait Gallery of Canada. When the former National Library of Canada and National Archives of Canada joined together in May of 2004, they became simply Library and Archives Canada. And when the National Museum of Science and Technology reinvented itself a few years ago, it became the Canadian Museum of Science and Technology. What on earth is going on?

The reason for this is the singular way in which the word 'nation' is used in Canada. Whereas in most other nations of the world, it is used to refer to a homogeneous whole - that which embodies all the geography and all the people of the country in question - in Canada, it is used to reflect the opposite, the constant presence of difference. And these differences represent the aspirations of groups of people to a separate wholeness within the body politic called Canada.

Let's begin with 'la nation franchise' - the French speaking population of Canada, mostly concentrated in Quebec. 'La nation' for them has a coloration of culture, society, language, a set of governing values linking the group, beyond any political intent, though that is most certainly there too. Hence Quebec's provincial institutions do have the word 'national' in them, like the Musee national des beaux arts du Quebec, or the Bibliotheque nationale du Quebec.

For the Marquis Pierre de Rigaud de Vaudreuil, the first governor to be born in Quebec, it must have been with great chagnn that he was forced to surrender the colony which he had so long wanted to govern, after the victory on the Battle of the Plains of Abraham in 1759 by General James Wolfe, who himself died in that battle. Yet it was the British who agreed to surrender terms afterwards which helped to ensure the continuation of French language, law and culture in Quebec. The concept of respecting roots in Canada and of expending effort to re-establish the old country in the new becomes a concept to watch - a foundation stone in the building of Canada of huge significance, one which differentiates Canada from the United States which embraced the idea, so seminal for its own development, of rejecting the old country in order to found what was intended to be a new social utopia.

The continuing ambivalent English/French relationship shows up in the stereotyping of French Canadians in portraits, for example as both picturesque 'habitants' in the work of the artist Cornelius Krieghoff in the mid-19th century, and as heroic voyageurs in works such as Frances Ann Hopkins' Shooting the Rapids of 1879, where she and her Bntish husband sit ensconced among well-muscled and intrepid paddlers guiding a canoe through tumultuous waters.

A recent portrait encapsulating this still unsettled relationship is that of Jean Chretien, a former Prime Minister of Canada. In fact, it is a form of self-portrait, organized by the photographer Andrew Danson who set up the camera and left the room so Chretien could select his own pose and take the photo. Chretien won three majority elections back-to-back, with an image as Me p'tit gars de Shawinigan', the 'little guy from Shawinigan'. But though French, he was consistently re-elected nationally, while he lost his popularity in most of his home province of Quebec. The boy scout salute he selected for himself reveals some of the resilience of the man.

The uneasy accommodation between the English speaking majority and the often combative French 'nation' in Canada is only accomplished through such ambiguous semi-assimilations which allow room for a respect signaled by the refusal to joust on the battlefield of the word 'national'.

However, much more than English speaking and French speaking nations inhabit Canadian territory. We also use the phrase 'First Nations', a phrase which tends to cover all aboriginal peoples except those who call themselves the Inuit (who used to be known as the Eskimo). While some First Nations have signed treaties, implicitly underlining their status as independent nations dealing with Heads of State, others have not, and regard all newcomers since the white man's arrival as settlers on their land, in their nations. Canada to them is blanketed with several overlapping nations, and gradually and very slowly their claims are being brought to the bargaining table, or to our own. or the world's, courts.

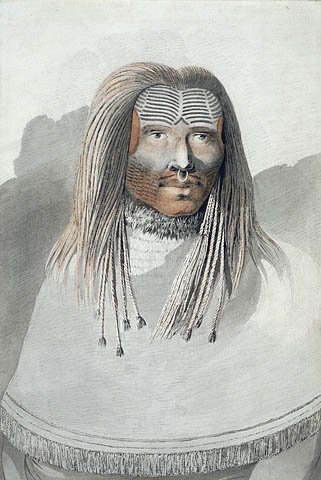

As with the English/French divide, portraiture reveals this see-sawing ambiguity in our relationships. For example, a drawing by John Webber of a man from Nootka Sound in British Columbia could be considered the 'earliest' portrait of a Haida, as it was made about 1778 at the first contact during James Cook's third expedition. But this opinion would only be true if a portrait is defined by whites. From a native perspective, the powerful collective portraits represented by ancestor masks have equal resonance as a definition of identity. Today, natives insist on making their own portraits, and they tend to look little like traditional white imagery, while acknowledging the inevitable hybridity represented by modern media. An example is David Neel's Kwagiutl Family Portrait of 1991; this print shows him with his wife and three children in symbolic form.

But Canada has done much more than recognize First Nations as nations; our history shows a unique contrast - we have both suffered the complete extinction of an entire native nation and, as though in an unconscious attempt at compensation, we have literally created a new aboriginal nation within our own body politic.

The first is the Beothuk of Newfoundland. An unassuming miniature portrait of Desmasduit, or Mary March, painted by Lady Henrietta Martha Hamilton, is the only portrait from life of a Beothuk. Her life encapsulates the tragedy of her race; she saw her husband and child killed, and was herself captured. Before she could be returned to her tribe as ordered by Governor Sir Charles Hamilton, Lady Henrietta's husband, she fell ill with tuberculosis and died in 1820, a few years before the last Beothuk of all died in 1829.

And the new nation we have created is the Metis, a people once called half-breeds, the children of a native parent and usually a French-speaking parent, a voyageur. The earliest photographs taken in Canada's west, made by Humphrey Lloyd Hime on an 1858 voyage, show M6tis such as the lovely Letitia Bird, who is seated on the ground dressed as a conventional white woman. In 1982, the Canadian Constitution recognized the M6tis Nation; and in 1985, the Alberta government passed a resolution committing the province to transfer the titles to Metis settlements to the Metis people. The resolution passed into legislation with the 1990 Metis Settlement Act. Canada is surely unique in this - a country which has both created a people and recognized them as a nation within its boundaries.

Just as unusual though, we have created a new land within our country, in response to the sense of identity of another group, the Inuit of the eastern Arctic. Half the Northwest Territories were separated out to become the new territorial land of Nunavut in 1999. So we are changing our nation's geography and political divisions to respond to the nations within our borders.

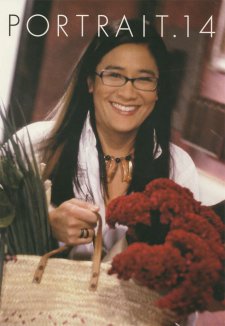

But we are still not done with stretching the boundaries of what 'national' may include or the changes it may engender in Canada. What of all those who are called 'hyphenated Canadians', following in the tradition of 'French Canadian' and 'English Canadian'? We know some of their faces, but unhappily, not always their names. What of the black or African Canadians, represented in rare images such as the portrait of a Good Woman of Colour, sketched by Lady Caroline Bucknall Estcourt about 1838-39? Or the Chinese Canadians, like the anonymous Chinese Seamstress, snapped by Robert Reford about 1888 in British Columbia? Or the German Canadians, like the anonymous German immigrants, photographed as they first arrived at Quebec City by William James Topley about 1910? Or the Japanese Canadians, like Kimiko Okano Murakani by Barbara Woodley, photographed on February 28. 1990, who suffered internment during the Second World War? Or any number of others who have come to Canada to start new lives and help to shape the country? Our ancient respect for their roots shows itself again in an official government policy of multiculturalism, in a Canadian Multiculturalism Act and a Minister of State for Multiculturalism. We take pride in not being the melting pot. In fact, we first had a citizenship act, defining a Canadian citizen, only in 1947, and we early accepted the concept of dual citizenship, allowing citizens to become Canadians without necessarily renouncing their citizenship in other countries.

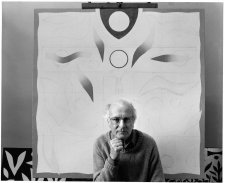

But even that is not enough for the multiple concept of nationalism in Canada. Our ideals -and many of our heroes - tend to be those whose accomplishments have been on the international stage, very often helping others rather than pursuing our own national goals. Prominent examples would be represented in the portraits of Sir Frederick Grant Banting, completed in 1925 by Tibor Polya; he was co-discoverer of insulin and winner of the Nobel Prize, whose work saved the lives of millions worldwide threatened with diabetes. Or Eugenia 'Jim' Watts, portrayed in 1940 by Frederick Taylor; she was a journalist working with Norman Bethune's blood transfusion clinic in the Spanish Civil War. Or Roy Thomson, Lord Thomson of Fleet, painte by John Bratby in 1967; he achieved fame as a newspaper and media magnate who moved to Great Britain to be equally successful and ultimately raised to the peerage. Or Marshall McLuhan, photographed by Yousuf Karsh in 1974; he was a communications guru who shook up our whole world view, portrayed by the first Canadian artist in any medium to achieve the status of a household name and a reputation with world-wide penetration. Or Douglas Coupland, painted by Laurie Papou in 1999; he was tbe author who defined a whole generation in the developed world, Generation X.

So there you have it: Canada does not use the word national in its national institutions because it is not inclusive enough for us. It suggests a singleness, an exclusive identity, which we have spent five hundred years growing away from, an assimilation to a single ethic which is not accepted by natives nor by any of the other pluralist and ethnically aware groups in Canada - and we are all part of one of those groups. In acknowledging our diversity, we also all recognize what Chief Justice Antonio Lamer said, when rendering a decision in favour of native rights in 1997: "Let us face it, we are all here to stay."

So for Canada, our national identity is not definable because it is not a place we have arrived at; rather, it is a journey we are still making.