"I don't know any other nation in the world where an iconic country singer would want to be photographed with a housewife drag queen superstar." John Elliott talks about his current work.

Your image in the collection of the Portrait Gallery of Slim Dusty arm-in-arm with Edna Everage has become iconic. Can you tell me how such an improbable image came about?

In 1992 I was in the Kimberleys where Slim and Edna were doing a concert together. Slim and Edna were friends and were pretty comfortable backstage and didn't seem to mind me with my camera. I only took two or three frames but somehow I knew it was a really important moment captured.

Subsequently I read in the paper that the National Portrait Gallery was going to open in Canberra. I contacted Andrew Sayers and said, 'Mate, I've got just the picture for your gallery!'. He said, 'Oh, post it down and I'll have a look' The next thing I knew it was on the front of the invitation for the opening of the Portrait Gallery by the Prime Minister!

I don't know any other nation in the world where an iconic country singer would want to be photographed with a housewife drag queen superstar. It's wonderful. They're mates and they were long-term friends and I think it says a lot about who we are as race of people.

You've been photographing Slim Dusty for a long time, how did that begin?

Growing up in Blackall, going to see Slim every year at the Blackall Memorial Hall was a bit like going to mass every Sunday, a bit of a religious experience.

Even as a kid, Slim's music spoke to me. I don't recall what it sounded like but his lyrics were about where I came from. I used to read Life magazine when I was eight or nine and the rest of the world seemed exotic to me. When I heard Slim sing about his experiences of the bush, for the first time where I lived seemed somehow to be exotic too!

I worked in radio for a long time. I played Slim's music and then managed to meet the man and eventually I got to take his picture. Little did I know that I would be travelling with the bloke and photographing him for over 15 years. We became really good mates but you know, I was doing something that I would've done for free.

There's a lot of connection in your work with country music singers, is that just because of your contact with Slim or is there something more for you in country music?

I see my photography as a tool to tell stories and I think country music is just another form of storytelling. There is a truth that's implicit in a real bush ballad that attracts me to the genre. You have to know what you're writing about to write a bush ballad. Being fairdinkum is a big plus in country music. I guess my background has drawn me to the music and the words and my curious nature makes me seek out the people who create it.

Your exhibition Thousand Mile Stare captures your love of the bush, the people and their stories. When people leave the show what do you hope is the impact of the show?

Even though 80 or 90 percent of the Australian population lives within 50 kilometres of the coastline there is an amazing connection to the Australian bush - even for city people. I'd hope that anyone who comes to see the show is engaged by the people because they all have a story to tell. I hope they go away thinking there are pretty amazing people out there and I hope that city people particularly have a new respect for the bush.

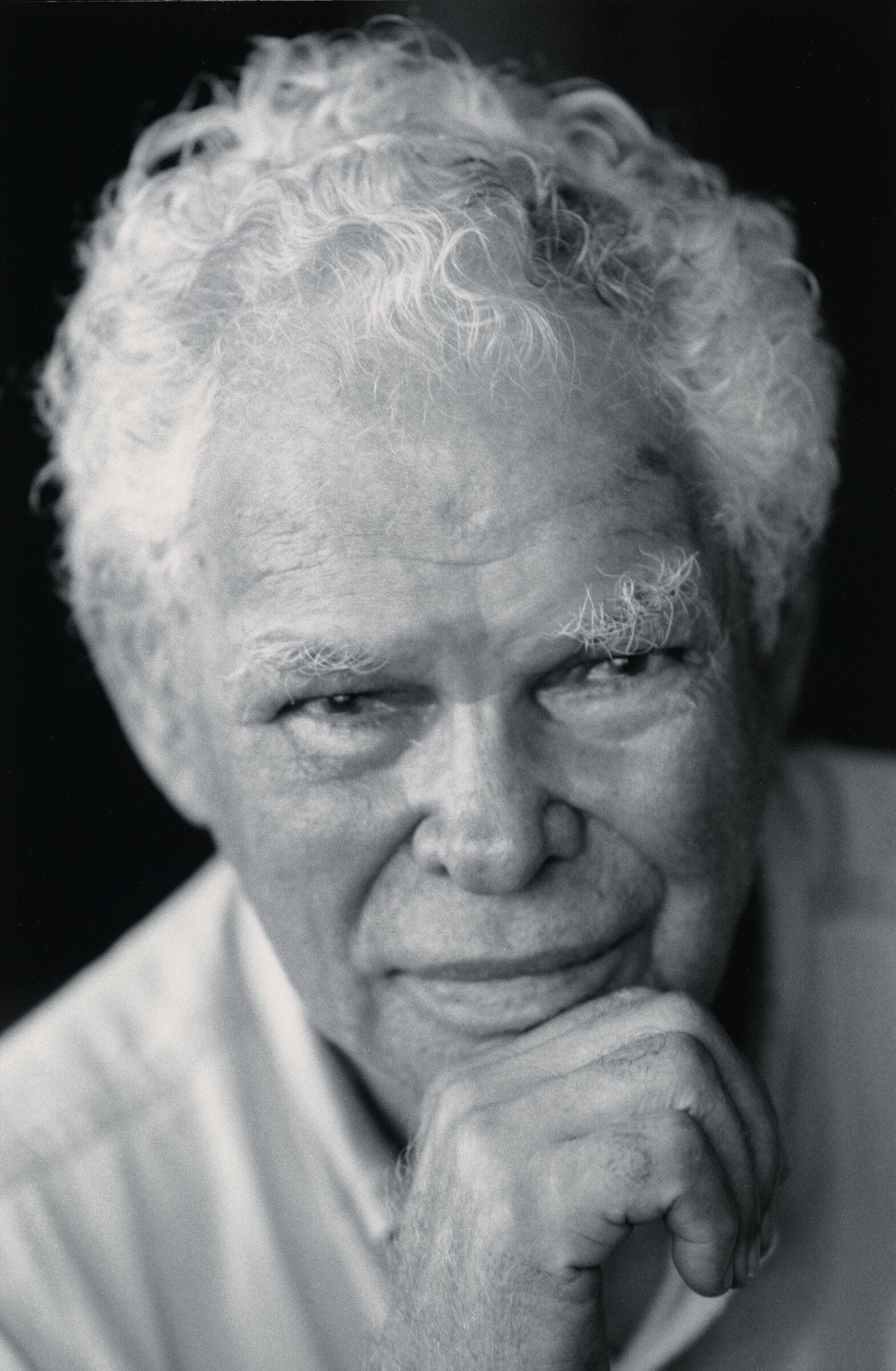

One of my favourite shots in the show is of the Aboriginal ex-drover and writer. Herb Wharton. I'd never seen Herb without his hat and I asked him to take it off. Herb's a really handsome man and has the most beautiful head of silver hair, so I decided I'd use the shot without his hat.

I was really thrilled to photograph an amazing bloke called John Shoobridge on Bruny Island off Tasmania about eighteen months ago. John must've been in his nineties - he has died since. When he was about 54 he called the family in one day. He'd always had this dream that he'd run away and be a stockman in the Northern Territory and he left it until he was 54 to do it! He had realty fond memories as a 54 year old getting off the plane in Alice Springs thinking, 'I've got to find a job'. I think the bush allows people to be themselves a bit more. Most of the people in the show are unique.

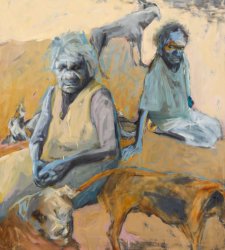

The three Aboriginal girls in the show are part of the Eather clan. Michael Eather, their dad is a white fella who married a traditional woman from Maningrida and they had three daughters. They're the most amazing girls and certainly their culture is a really strong part of their identity. They spend half their time in Managrida and the rest of their time in inner city New Farm, Brisbane. They are street-smart about living in the city but you can see there is a wisdom in their eyes because they are connected to the land where they come from.

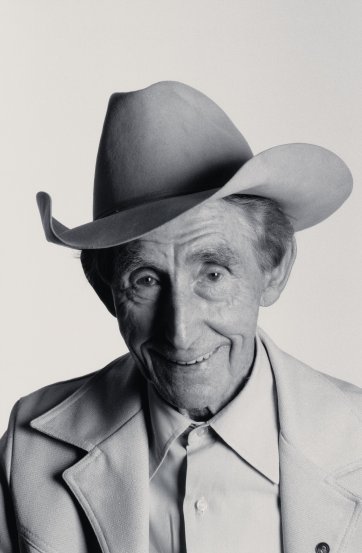

Smoky Dawson is a legend. He's well into his nineties and his wife, Dotty is even older than he is I He still lives life with a passion and is still as sharp as a tack. In the old days he was a real entertainer, he was a whipcracker, sharpshooter, rope twirler as well as a singer. He used to throw tomahawks at his assistant. I was out at his house in Sydney, it's only four or five years ago, and he's still got the tomahawks. I said, 'Oh, what are these, mate?' and he said. 'I used to throw them. I've still got the tree out the back I practised with'. Then he said, 'You come and stand next to the tree with your camera and I'll throw the tomahawks at you.' I trust Smoky but I didn't trust him that much I He has had an amazing life. Back in the sixties he had the Smokey Dawson Ranch Club. You could sign up to become a member on the back of a Kellogg's Cornflakes packet. Even Paul Keating was a member along with around 600,000 other people. He is still such a sharp fashionable dresser. He always looks immaculate. He's got the white hat and the white jacket and looks great. People like Smoky inspire me.

And Kasey Chambers, you've been a friend of hers for a long time?

I first meet the country singer song writer Kasey Chambers with her family in Sydney in the early nineties when I was editing a country music magazine. Kasey was just a kid but she was just incredible from day one. The whole family made their living shooting rabbits across the Nullarbor Plain for six months of the year when Kasey was a youngster. When the kids were growing up they'd listen to their dad's records and they'd sing around the campfire. Their family band was called the Dead Ringer Band. Kasey is the real deal and is not really writing songs to be top of the charts - she's writing about what is important to her. As it turns out her words and music strike a major chord with the rest of the nation. Jimmy Little is one of the really great, iconic Australians. He's a fantastic singer and an incredible man. He's quietly gone about his work. He was a pop singer in the early sixties. But he probably spent maybe 20 years there in the middle where he didn't make a noise about it but just worked with young Aboriginal kids. He was a role model for young Aboriginals and lot of white kids as well. It's fantastic that he's had a rebirth in his singing career and he's singing better than ever. He's one of the few people I know that likes to talk more than I do! I love that shot of Jimmy. He was sort of strumming his guitar, looking off into the distance there, lost in a moment. That's the shot we used and it's a beautiful one.

John you covered a lot of ground photographing these people. How did you manage to get around such distances?

There's nowhere close when you're talking about the Australian bush. One of the things I want to talk about, a lot of people call it 'the outback' -1 call it 'the bush'. When I was growing up in Blackall I don't think I'd ever heard the word 'outback' until I was 16. Outback is definitely a city word. They had the Year of the Outback and I'm thinking itls obviously a city thing because if you live out there you live in the bush, you don't live in the outback. So when we decided to do this show we wanted it about people having connection with the bush and we felt an obligation to get people from everywhere. So we covered a lot of Queensland, a lot of Northern Territory, New South Wales. Spent a fair bit of time in Western Australia and briefer visits to Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania. I think I drove 700 k's one day to get one photograph. Some days we wouldn't see another car for four or five hours. It's a big country out there.