It is the very nature of photography that often brings about its destruction. Family photographs often assume a treasured status over the passage of time and can come to be valued as tangible evidence of a personal and familial history.

When you combine this significance with their inherent portability and subsequent susceptibility to damage, it is little wonder these images are often quite transient objects. Our photographs are often, quite simply, loved to death. Most of us would have historical photographs on permanent display around our homes or other images which are pulled out from the back of a cupboard from time to time to refresh our memories. Unfortunately, the oils and acids on our fingers when we handle these photographs can damage the photographic emulsion and cause tarnishing of the silver gelatin coating, just like a silver trophy or cutlery. Physical handling also increases the risk of creasing, tearing and warping. Those photographs we protect in frames and leave on permanent display often fare no better, falling victim to fading from excessive light exposure or suffering browning of the surface (or 'foxing') from irregularities in atmospheric conditions.

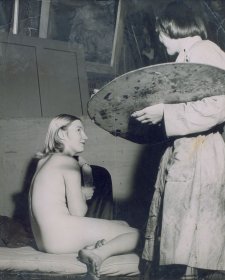

Like many old personal photographs, the recently gifted portrait of Barbara Blackman was displaying substantial signs of its history. The image was badly creased and torn and the emulsion in many areas was cracked and quite unstable. The warping of the surface was very significant with the top right and lower left corners nearly meeting in the middle.

The Gallery enlisted the aid of local paper conservator, Kim Morris (Art & Archival Pty Ltd), to help preserve the photograph prior to its acquisition into the collection. The labour intensive process consisted of cleaning the surface of the photograph with a water/ethanol solution in order to remove the soiling and to take off the tarnished silver of the original silver gelatin emulsion. He then brushed on a new gelatin coating which lifted the almost sepia-toned browning of the surface and restored the glossy black and white colouring. The new gelatin water solution will help to stabilise and protect the cleaned image and reduce the rate of silver tarnishing.

It was then a matter of addressing the tears and creases. In order to reverse the warping and return the image to a flat state, Kim applied a conservation tissue backing to support the photograph and flatten the image very slowly in stages under static pressure. After a few losses were in-painted and stains reduced, the work was remounted in a custom-made, acid-free, archivally-sound mount board.

As you can see from the image on the previous page the results are quite remarkable and the work can now be appreciated in a state much closer to that in which it was first created. Unlike modern airbrushing techniques, the scars have not been completely hidden which ensures that the photograph retains its historical presence (something that would be absent from a digital reproduction).

However, the job is not yet over. It is now the responsibility of the Registration section at the National Portrait Gallery to ensure optimal display conditions for the photograph are maintained including monitoring the light and atmospheric conditions and regular rest periods from light exposure in the store in an acid-free archive box. These measures will guarantee that this important photograph will be able to be appreciated by the public for many more generations to come.