The son of a military officer, Teddy frequently explores pacifism and anti-authoritarianism through his works, drawing on aesthetic influences as diverse as street art, advertising and Fauvism. His major installation Love tanks at the Singapore Art Museum in 2010, marked Teddy’s first foray into monumental-sized installation, although its plywood base belies its size and weighty themes. Teddy considers himself primarily a painter but uses sculpture, assemblage, casting and installation to extend his symbolic language. Teddy has been involved in a number of arts projects based in communities in his hometown of Yogyakarta, where he lives and works.

Mining the self

MeetingTeddy for the first time was an interesting experience. It involved new tattoos (on him) piercings (on me) and huge hangovers (for everyone). The piercing didn’t last, but the most memorable souvenir I have from that day was a t-shirt. Silk-screened on the front was Van Gogh’s famous Self portrait with bandaged ear. Recently I asked Teddy what the significance of that painting is to him.

… seeing Van Gogh’s self portraits raises the question for me as a painter: what was his motivation for painting himself?

The first time I painted my own face was spontaneous and without any motivation/concept, in 1995. I still have that work … I made it with ink on paper … it was only after that I began painting my own face often. And a few times I have copied Van Gogh’s self portraits as a parody. For me, Van Gogh was a painter who really loved the world of painting.1

Teddy’s art practice operates as a method of investigating social, historical, familial and environmental problems, and his selfhood within that environment. Self portraiture is an integral part of that process. Since that first, spontaneous work on paper, he has used his own image as the central motif in many works.

Often returning to familiar motifs, Teddy has built a recurrent symbolic language; shapes, media and objects. A face reduced to a few lines, a stone head, the outline of a house, his own head cast in clay, aluminium, bronze. Mechanical objects, especially the wheel, hold a special significance for Teddy. These are symbols, Teddy tells me, indicating colourful tattoo of a locomotive on his arm, of humans as thinking beings.2

In spite of his admiration for society’s industrial achievements, a significant influence on Teddy’s practice is the desire to rebel. Sometimes the struggle is internal yet universally relevant. His vehement statements against war and violence often include self portraits. His 1997 installation The choir who can’t say no incorporated locally specific symbols (236 yellow fibreglass chicken heads), mirrors and photographic self portraits, implicating both the viewer and Teddy as subjects, while his major 2010 solo exhibition WAR also included self portraits as various subjects, from victim to perpetrator.

These protestations reject not only the Indonesian military’s dominance – which during the New Order extended to power in fields of business, politics, culture and communications – but are also in opposition to his family’s military background, his transient childhood spent on military installations, and also the role of international militaries in global politics. It is a personal and political resistance. Ariel Heryanto draws attention to the central role that ‘ideas’ generated by artists, writers and universities play in resisting the hegemony in Indonesia.3

Teddy’s use of his own biography is a part of that larger history of creativity and dissidence in Indonesia. Writers such as Nobel Prize nominee Pramoedya Ananta Toer and poet Rendra have drawn on their own experiences in calling fellow citizens to arms; visual artists including Hendra Gunawan and Nindityo Adipurnomo employ self portraits to condemn the political and social status quo.

For Teddy, there is also self portraiture as a process, a beginning for works that may not manifest as self portrait in the final iteration. When faced with a blank canvas or a creative block, Teddy’s first resort is self portraiture. When responding to ‘nature and life’, he uses his own image rather than a generic figure. In this incarnation, Teddy is an ‘everyman’ exhorting an ethical or political critique.

Painting becomes a place to untangle the contents of my head with pictorial concepts, because really for me painting is a picture which has been complicated, convoluted and simplified. A picture that has been extended …

We have a broad theme; nature and life. We are inside it.4

There is also self portraiture created to illustrate a specific self, subjectively experiencing an objective and common reality – such as parenthood, political unrest, social change. In his striking installation, Top of the roof 2008, Teddy installed a series of brass busts cast from his own head, on a bamboo roof structure. Through these busts Teddy explores his social position and self-image as it has changed over his life. One sports a Mohawk with mouth open in enraged scream; another calm countenance bears the decorative headdress of a Javanese Buddhist statue. Still another has its face removed altogether, ground down to a white plane. This one, he says, is about the desire to self-destruct, its creation cathartic, the grinding away of his own face was a chance to dispel the demons.

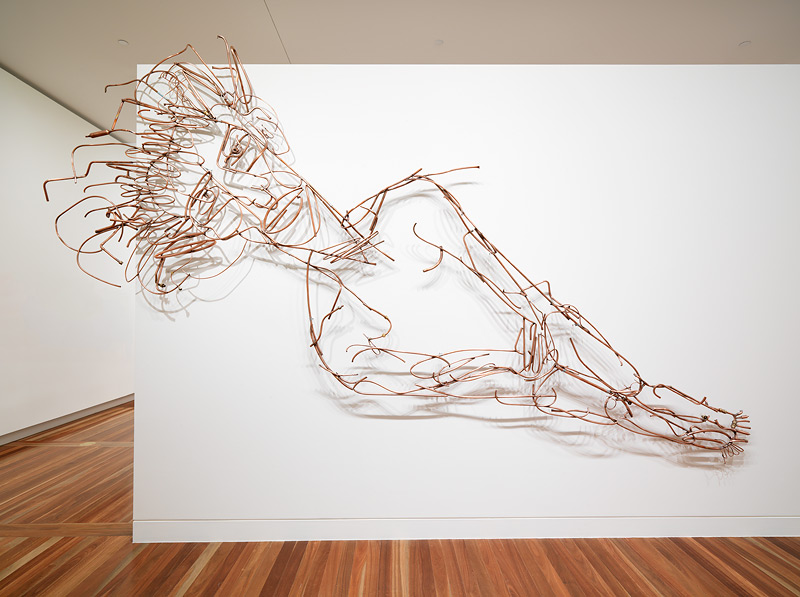

Refound the line 2011, the work created specifically for this exhibition, echoes an earlier work in metal. Found line 2008 was a drawing in three dimensions, mapping the contours of Teddy’s face in found steel (recycled from concrete reinforcement) painted alarm-red. Hanging a few inches from the wall, it cast its larger-than-life shadow slightly offset from its physical embodiment. The confusion of lines – the concrete and the ephemeral, the outer and the inner – forces the viewer to unravel the drawing shape-by-shape. Where is the form? Which dimension is forward? This work was created in a year of upheaval for Teddy, the year his daughter was born. If a self portrait is an attempt to communicate the internal dialogue of the artist, what do these layers of lines tell us? These two drawings appear to be endlessly entangled; in fact they never touch. However difficult it is to separate them, we are cognisant that their interplay is no more than cause and effect. The concrete remains the same, but a shift of light will change the inner self in an instant.

Elly Kent

Researcher, artist, educator, translator and writer.

1 S Teddy Darmawan, email correspondence, 10 May 2011.

2 Interviews with the artist, December 2010, during the author’s Asialink residency. Each year the Asialink Residency program sends forty Australian writers, performers, artists and arts managers to live and work throughout Asia.

3 Ariel Heryanto, State terrorism and political identity in Indonesia – fatally belonging, London and New York: Routledge, 2006, p.188.

4 S Teddy Darmawan, Keras Kepala, (exhibition brochure), Yogyakarta: Rumah Seni Cemeti, 2001.