His work, which has been described as obsessional and gruesome, draws on his interests in psychology and memory, and his imagery is influenced by icons of visual culture in the Philippines. Legaspi references Catholicism, particularly the more violent aspects of crucifixion and martyrdom; horror films and the spectacle of violence; taboos around sexuality, homosexuality and the body that operate in Filipino society. He has held solo shows in Philippines, the United States, Australia and Hong Kong. Legaspi lives and works in Manila, Philippines.

Half-light

In an old Tagalog confession manual the admonition is clear with regard to the graven: ‘Sumba ca caya sa anomang di sucat sambahin?’ Did you worship that which does not deserve to be worshipped? The prohibition of image or likeness might have found itself in tension with the surfeit of colonialism’s icons that circulated for the conversion of Filipinos for around four centuries, beginning in 1521. This fraught history of image as an instance of control and salvation might be key in understanding how the likeness of an artist surfaces in postcolonial painting.

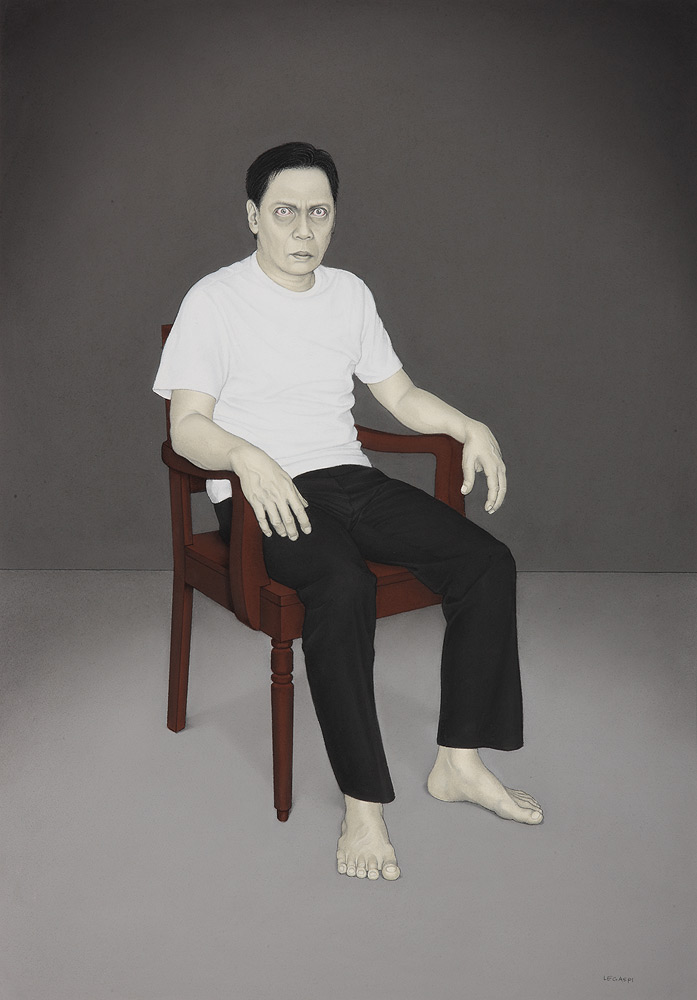

Legaspi’s art, as may be discerned in the portraits for this exhibition – sufficient in its naked pieties and sacrileges – is to a certain extent confessional: it is an unburdening of transgression, an address to authority, an affront to creed. Here, sins are revealed copiously, not to be consigned to a past of contrition but to inveterately haunt the present. It is also a revelation of the artist’s history of skills, his intimacy with the body as a biological organism, being a keen student of the flesh that is undeniable and irresistible. But there is finesse in this disclosure, no sign of the mess of a medical exercise, though missing too is the fastidiousness of a fine-arts discipline. Legaspi crosses the gap between the depiction of, let us say, ‘bare life’, and the aesthetic of a confessing subject, one who remembers and ensures the persistence of memory in figuration.

This figuration is delicate, painstaking and time consuming, but ultimately tenacious, clinging like a dream. Legaspi explores the medium of pastel, a variant of crayon, tinged with wax and therefore frangible. It scatters, difficult to control, because the form it inscribes is not opaque or translucent; it is granular. The grains that cohere on a surface that is equally fragile must be diligently and religiously gathered, perspicaciously put in place. While the material may not have the density and rondure of oil as it is absorbed by canvas, pastel on paper achieves a wondrous tint, a stark monochrome that bedevils. Building up layer on layer of tones, from light to dark, the artist merely dabs the ridge or rim of the pastel, which he breaks every now and then to find a certain edge like the tip of the brush. He then contours using graphite to create a semblance of boundary and cast the unruly particles in an armature that is as flimsy. There is no stroke, so to speak, only smearing.

This procedure is part of the confessional process. Legaspi’s choice of facture is formative, a reference to his critique of ‘painting’ as a canonical technology and a return to his aversion to colours being mixed and applied on a ground, a childhood experience with aquarelle that has not left him. It is also a challenge to the rigidity of oil, an almost patriarchal influence over form. Furthermore, it is about the body, how it is rendered sharp and deep to the point that it transcends the worldly and the realism of artifice; it becomes unnatural, inauthentic, phantasmatic. The figure emerges from its context – a spare, ashen or pitch proscenium – as a spectre, with a dissembling substance. And so whatever arises from the void of paper through porous matter is equivalently suspended in the tension between grit and apparition, society and autobiography.

The pastel series of Legaspi converses dialectically with his charcoal suite, which practically tars the surface in which the more automatic inscriptions serve as foil to the highly refined and stunning naturalism. A plethora is unleashed by this impulse, signified by words like ‘flood’ and ‘phlegm’ that title the forays; the flow or the viscosity of drawing may be co-extensive with an effusive unconscious coming to light. The charcoal projects are installative in conception and surround the audience, engulfing them with small drawings that supplant the wall and threaten the security of a supposedly fully formed identity. The mark of charcoal is cursory and nearly random, just enough to singe the paper as it were and form the silhouette of fleeting reality like a winding path, an intriguing object like a coffin, a man bathed in gossamer light, the inclement sea sketched out as a child would, or the word ‘mama’ written as if on a wall. In previous installations of charcoal works in Ashiya, New York and Brisbane, the sensorium is unerring if it entombs spectators, forcing them to be shrouded in the half-light of drawing, in a room of terrifying grisaille. This all-over sensation stems from the fragments of pictures mutating on a concrete exterior and sheds its skin of a lived, imagined, repressed, streaming personal history.

As the exposure is in the details, how much of it ought to be insinuated is an ethical question. How much can we pry and how much can the encounter be truly reciprocal? Legaspi confides that there is jouissance in carrying out the grisly as if to say that trauma is worked out in the meditative act of figuring its symptoms, ultimately making us rethink psychology as the sole basis of our intuition of his art; rather it is the ‘sensory biography’ of an at once contemplative/tempestuous prevailing that may help us divine it.

Patrick D. Flores

Professor of Art Studies and Curator

Vargas Museum of the University of the Philippines