An academic and writer, with strong intellectual influences, she is often driven by a sense of social justice and is conscious of the way in which the state relates to its constituents, particularly through constructions of architecture and monument. Bamadhaj’s work is often strongly critical of the political and social machinery that drives communal direction. Bamadhaj’s practice is informed by her unstable position in terms of geographic origin and her personal interest in regional human rights. In 2002 she undertook a year-long Nippon Foundation fellowship in Yogyakarta, where she has lived and worked ever since.

Not talking to a brick wall & Landlocked:

Architectures of personal space

In Nadiah Bamadhaj’s work, the notion of person is inextricably tied to notions of place. Over the past decade, her practice has been motivated by a strong personal interest in political events and social phenomena that have shaped or affected her identity and outlook, expressed through varied interpretations of their geohistorical positioning. It seeks some truth or reason behind the posturings and assumptions offered up to ‘local’ and ‘global’ audiences alike as a gloss on the historical and contemporary reality of her regional nexus, incorporating Malaysia, where she was born and grew up; Singapore, the long-time seat of her paternal family history; and Indonesia, a site of traumatic violence that she has chosen as a current base.

Subjectivity in Nadiah's practice is dialectic – the personal is clearly a space of competing agendas of political, historical, religious, ethnic and sexual identity. Where her own image appears, it is always as both object and objectifier, pawn and chess player, as a reflexive strategy that tries to understand the self as a political, social, historical subject.

Architecture and landscape, or topography, provide the signifiers of this subjective context. The two works highlighted in this exhibition represent two trajectories of the situated self – in family history, and in contemporary habitat, treated as video-based in the first instance and as collaged drawing in the second.

In both works, the subject is portrayed as trapped, or at least located in architecture, an imposed cultural and social context. It might be useful to think of Nadiah's work here as both physiological – describing the functions of place in relation to human experience, and physiognomical – describing the physical (emotional and psychological) characteristics of place, as intrinsic to a portrait of self.

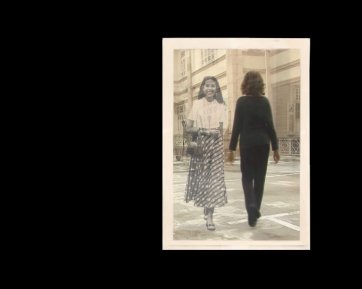

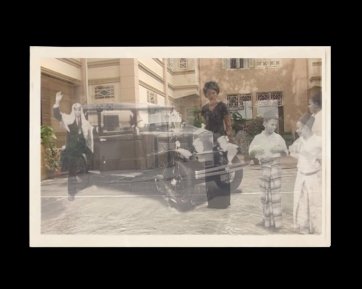

Not talking to a brick wall 2005 is perhaps the most intimate of the artist’s works, directly interfacing with her family history. Contemporary video footage is collaged with historical photographs of her paternal family home at 6–10, Lorong 29, Geylang, in Singapore, drawing out the texture of remembered place through the sepia tones of found photographs and the sounds of house and street. What might have been a rude re-entry into history is softened by a sincere desire to communicate with the familial past.

Three contemporary female members of the family, dressed in black, walk through the house and old photographs of the house, at turns quizzical, interrogative and satisfied. The performance of each of these female actors is understated, gently questioning and smiling at the meaning of the memory of each image, walking through or around them. Family relationships are hinted at – Nadiah’s cousin retraces the footsteps of her late mother, shown here walking out as a smiling young girl. Nadiah’s sister looks bemused at a group of boys – perhaps young and naughty versions of uncles – lurking around an expensive new car.

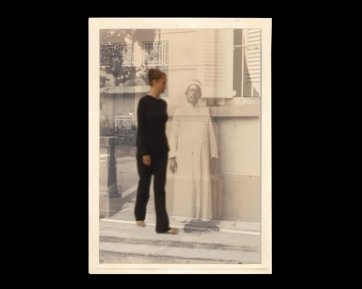

In the final sequence, Nadiah stands still and poker-faced in a corner as the image of the family patriarch turns as a page through her image, and she is left standing as time moves back and forth, like a legacy in question. The work appears to be a simple effort to draw meaning from ‘familial roots’, and a commentary, in its title, on the difficulty of reconciling with one’s past, now broken by national boundaries,1 which proposes some form of historical engagement against a haunting sense of loss.

Landlocked forms part of a larger body of collaged drawings shown in the 2008 exhibition Surveillance, which sets out to examine the politicisation of habitat in contemporary Malaysia. Based on the artist’s own experience of living in the suburbs of the central Klang Valley, and her research in social geography, the works in Surveillance investigate ideas of architecture and town planning as an expression of political strategies to contain social and political behaviour. The design of suburban housing and location in this context is seen to regulate the daily life and preferences (for convenience and stability) of citizens, facilitating their control by the state.

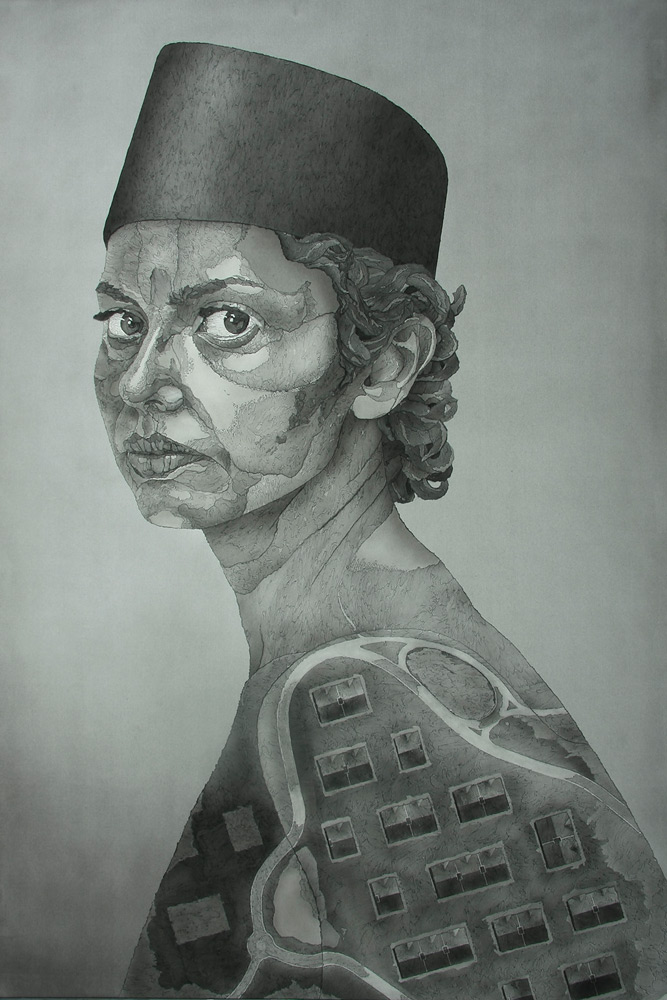

In Landlocked, the topography of a Klang Valley suburb is integrated into the artist’s self portrait, its regular rows of townhouses laid as tattoos on her upper arm. The charcoal on paper collage of landscape and skin emphasises the tactility and texture of this ‘mapped’ experience, its emotional presence in a cold strategic context.

A previous self portrait in landscape, Menelan kejut, termuntah diam 2006, also shows the artist wearing a songkok, the traditional Muslim headwear for men (Malay Muslim women conventionally wear the hijab veil, or tudung, to cover their hair as an expression of modesty), her head rising like a mountain from the landscape, a symbol of power and perspicacity, looking over the scene. This ‘cross-dressing’ is a not-too-subtle if ambiguous provocation, questioning assumptions of gender and religious identification. In Malaysia adherence to Islam is constitutionally tied to a Malay, bumiputera identity,2 and Nadiah would be identified as a Malay Muslim woman, although she is of mixed parentage.

The expression on the artist’s face in this image is one of palpable defiance and scrutiny. She is at once ‘landlocked’ in a surveyed territory and its surveyor, making an argument for the possibility of self-empowerment through an intelligent understanding and knowledge of the agendas shaping one’s immediate world.

Beverly Yong

Director of RogueArt

1 Singapore joined Malaya, Sabah and Sarawak to form the Federation of Malaysia in 1963, but was ‘expelled’ two years later following racial riots and political disagreements; it gained sovereignty as the Republic of Singapore in 1965.

2 All Malays are defined as Muslim in the Malaysian Constitution. ‘Bumiputera’ is a political term, which may be translated as ‘son of the soil’, used mainly to describe the Malay community, the ethnic/cultural majority, differentiating them from other Malaysian citizens, although it also refers to other indigenous ethnic groups.