His themes draw on history and memory; collective consciousness is explored through personal and familial references. His characters are part autobiography, part nostalgia and part social commentary. Although the viewer is invited into the performance space – frequently a public space – Chopra consciously precludes direct interaction with the audience. The focus of the artists’ interaction is instead with time, place, his visceral self and his own processing of the experience through drawing. Many of Chopra’s performances originate in Mumbai, but are often re-imagined in different cities around the world. Although not explicitly politically motivated, Chopra’s performances have at times attracted intervention from authorities, which the artist says points to the ongoing critical capacity of drawing and performance. Chopra exhibited in the 2009 Venice Biennale. He now lives and works in Mumbai.

Beyond the Self

For ninety-six hours in May 2009, artist Nikhil Chopra performing the character of Yog Raj Chitrakar resided at Les Brigittines, a baroque chapel in Brussels, recently converted to a theatre. He left this abode every morning, traversing the city and scaling Galgenberg Hill to reach the imposing Palais de Justice/Justitiepaleis, a vantage point that offers sweeping vistas of the Belgian capital. Chitrakar covered his canvas with charcoal drawings of the city’s panorama, distinctly divided into two halves, indicative of the divisions between the French and Flemish-speaking populations that inhabit it. Evenings were spent back at the chapel sewing these two halves together, producing a dramatic, 16 metre long backdrop for Yog Raj’s final pose as a Greek goddess – an allusion to the neoclassical influences on the city’s identity and built environment (Yog Raj Chitrakar: Memory drawing VI ).

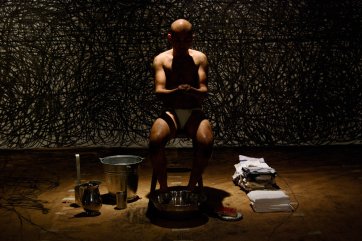

Nikhil Chopra operates in the interstices between theatre, installation, photography and live drawing, brought together in elaborately constructed and staged performances, lasting up to a few days at a time. The artist mines personal, regional, nationalist and colonial histories to create characters who are then translated into his performances. The enactments – choreographed in part, improvised in part – often extend beyond the four walls of the museum or gallery and into the surrounding landscape of the host city, which finds itself transcribed/appropriated into the performance archive by means of the character’s sketchbook. Chopra’s characters draw upon his sensibilities, influences and upbringing in an upper middle-class urban Indian family descended from land-owning aristocracy, yet they are not faithful toautobiography, taking on a life of their own during the performance.The artist employs carefully conceived costume changes, appearance alterations, sets and props as signifiers of identity, fairly fluid and constantly reinvented. As each performance progresses, rituals of transformation, usually informed by common cultural practices, mark the shifts between personages. Audiences observe the characters’ meticulous, mute transformations, yet their role isn’t merely to witness the itinerant artist and his assumed identities. A tangible tension exists between the performer, who maintains a vow of silence, and the spectator, who can follow and look from close quarters but is never privy to the act’s entirety. This prompts unexpected reactions, imagined narratives and a multiplicity of interpretations from the audience, activating its participation in a work that itself challenges accepted histories and conventions of class and gender. The artist provides numerous visual and gestural clues as he urges his ever- changing audiences to question the construction and representation of his characters – their behaviour, perception, and position in the social hierarchy.

Nikhil Chopra’s most recent and well-travelled character, Yog Raj Chitrakar, is aptly named after the artist’s grandfather, Yog Raj Chopra. This peripatetic draughtsman – modelled as a turn-of-the-century landowner, landscape painter, aristocratic dandy – has inhabited art spaces and public squares in New Delhi, Srinagar, Mumbai (Yog Raj Chitrakar: Memory drawing X ), London (Yog Raj Chitrakar: Memory drawing V [ Part I ] ), Oslo (Yog Raj Chitrakar: Memory drawing V [ Part II ] ), Venice and New York. The ongoing series titled Memory Drawing (2007–ongoing) charts the chitrakar ’s(picture maker) journey as he ‘pitches his tent’ in each host city, engaging its people and landscape in silent dialogue. Large-scale charcoal drawings emerge from these interactions, often capturing the iconic cityscapes of the world’s capitals, epicentres of globalization and hubs of transnational migration, past and present. Chopra usually begins his performances in the gallery or museum space, a tableau vivant where both rehearsed and improvised actions are performed. As the work progresses, the character embarks on a journey through the city, navigating its streets, traffic, climate, etc., attired in silk, tweed and linen. Chitrakar identifies a site whose history and current standing in the city embody the realities, contradictions and peculiarities of its history and people – Ellis Island in New York, Galgenberg Hill in Brussels, Hyde Park in London, Lal Chowk in Srinagar. As he sets up his studio and begins to draw en plein air, an audience begins to collect – tourists and locals, young and old.1

Once Chitrakar has successfully transferred his impressions onto canvas or into a sketchbook, he continues his journey, which will eventually lead ‘home’, where these reflections are displayed. The tedious journey through the city and the effort involved in producing these large-scale drawings is an exercise that Chopra hopes will initiate deeper reflection on the nature of work and its physical effects on the body:

I go through this whole process of making marks, getting dirty, washing and then wearing the gentleman. So that wearing the gentlemen becomes very much part of the performance. And then as that gentleman is worn, that gentleman also gets ‘worn’ … You see him transform from this crystal clinking, silver cutlery eating monsieur to a weather beaten, exhausted coal miner perhaps, covered in soot from head to toe, blackened absolutely… There’s for me where the critique lies. It’s the breaking down of the gentleman, rubbing this gentleman’s nose in the dirt, having him deal with the dust and the ash of charcoal and the blackness of charcoal, really takes him away from this ‘whiteness’, if I were to think of it that way… All of that stuff is where it really does go back to Brecht because how does one amplify the ‘working’? If you make a worker working then you see a worker working but when you see a gentleman in a tailcoat working, then you really think about ‘working’ a little harder.2

Rattanamol Johal

Postgraduate at The Courtauld Institute of Art, London

1 Of the act of documentation through drawing, Chopra says,

I think drawing or making maps or taking photographs or making images of something … [is] … an act of claiming ownership over it. My take on it is to reclaim a certain kind of history, to return, in fact, [to] this orientalist discussion about the Western traveller coming to the East and making documents and taking them back home. I want to be the oriental, perhaps, that comes to the West and makes drawings … And makes chronicles and perhaps goes back home to India with … documentation of that.

Interview with Nikhil Chopra by Tom Dodson, New York City, 9 November 2009, Champs Not Chumps, http://champsnotchumps.org/episode_3/transcript

2 Nikhil Chopra, interview by the author, 13 February 2011