His practice has an improvisational and experimental approach that intersects between mixed media, painting, sculpture, installation, shadow puppetry and performance that often makes use of found and sought materials. After migrating to Australia in 1995, he became interested in ideas about memory, mobility, exchange, collaboration and the experience of moving back and forth between different cultures, examining how these interactions can change ways of thinking. Through immersive exploration of intertwined themes of colonisation, migration and globalisation of culture, Reamillo has collaborated with community groups through workshops in regional Australia and overseas, creating a number of participatory ‘social sculptures’ in the form of ‘vehicles/ vessels/crafts’ created in response to local contexts and histories. Reamillo has a long standing collaboration with Australian artist Juliet Lea, their artistic partnership dubbed Reamillo and Juliet. He currently divides time between Perth and Manila.

Jose Rizal though the gaze of Alwin Reamillo

Like many of his contemporaries Alwin Reamillo’s childhood hero was Jose Rizal. Since his early work in the mid-1980s Reamillo has frequently incorporated images of Rizal in his sculptural assemblages, perhaps remnants of youthful fascination mixed with the leader’s popular usage as a national icon. Jose Rizal (1861–1896) was a brilliant polymath, writer, architect, opthalmologist and reformation advocate and has long been fêted within everyday Philippine culture and, for many, is the foremost symbol of nationalism. As expected, the 150th anniversary of Rizal’s birth in 2011 was commorated with great acclamation and fanfare across the Philippines. Various forms of memorialisation abounded in the nation, including the erection of a 6.5 metre statue in Rizal’s hometown of Calamba, Laguna, the latest in a long history of commemorative monuments.1

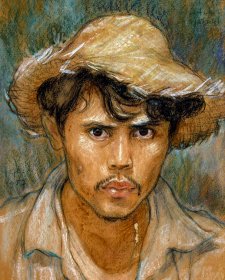

At the time of the anniversary, Reamillo commenced a new series connecting the image of the revered national hero with his own image. The pairing of these two highly constructed identities plays with the idea of self and other; overtly posing comparative and comparable questionings and farcically employing parody and paradox to talk of ‘Rizal the hero’, the ‘myth of the nation’, through its juxtaposition with one of Reamillo’s own fictional personas, Arnulfo Tikb-ang. At the same time it continues his enquiry into self, family and identity. This personal enquiry, commencing in the mid 2000s, engages with an extended notion of self although more commonly explored through conceptual portraits utilising pianos and by way of familial objects and photographic representation, principally focussing on his late father Decimo Reamillo.

Yet this personal enquiry inevitably speaks of larger concerns; namely the socio-political and cultural history of the Philippines and, at times, that of his semi-adopted country, Australia. Reamillo continually plays with the conflicting discourses ever present in the Filipino neo-colonial setting and astutely reflects on history and its affect on contemporary culture, employing metaphor, mimicry, humour and camouflage. In many ways, his current investigations extend beyond Rizal, and can be alternatively read as a portrait of the Philippines with all its disparate configurations and contradictions.

Reamillo constantly fragments, manipulates, and retranslates often prescribed historical and contemporary interpretations, languages and symbols from popular culture embroiled in this dissonance of discourses. The fascination with (re)interpretation and transference sees him continually mix disparate references to propose new meaning with mutability and impermanence accepted and desired corollaries. Through his signature of layering meaning, Reamillo’s work is charged with a palimpsest of provocations and interpretations requiring the viewer to invest time to consider the various associations and comparative juxtapositions.

The mixing of metaphors and moving from one frame of reference to another is clearly evident in Ang retabla Rizalista (Relikaryo ni Arnulfo Tikb-ang) The Rizal retablo (Reliquary by Arnulfo Tikb-ang), the sculptural wall retablo included in the exhibition.2 Presenting one of his pseudo autobiographical selves as the maker, a kind of anti-hero, Reamillo incorporates a number of recurrent metaphor-laden motifs in this work, notably the matchbox, crab and piano. The crab appears as part of the artist’s formal self portrait and again in the reliquary, and in addition to referencing personal memories is used to denote the beach, as the first site of colonial contact, as well referencing ‘crab mentality’.3 The matchbox forms the sculpture’s foundation and, along with the piano, has strong associations with his formative years. At the tender age of four the childhood discovery of lighting and playing with a match, in this case surrounded by highly-flammable solvents and varnishes, caused almost near devastation to the family piano workshop. Another motivation is Rizal’s image on the ubiquitous matchbox in the Philippines. As Reamillo explains, ‘For me, Rizal’s face on the matchbox is a kind of trivialisation – his significance reduced to a common day kitchen implement is far removed from the ideas that he represents. Most know Rizal as a matchbox, similar to his face on the now devalued one peso coin.’4

Shifting frames of references is manifest in Ang retabla Rizalista and observed immediately through the matchbox. The reanimation of emptied and spent receptacles remains a staple exploration in Reamillo’s practice and evident in the repurposed matchbox and reworked crab carapaces. Now devoid of its original meaning, he reanimates the matchbox receptacle to incorporate unfixed, provisional and evolving notions about self and other. Furthermore, his continual deployment of wordplay involves a constant shift between Tagalog and English references with frequently integrated Hispanicised adaptations. The word ‘matchbox’ can be reinterpreted as ‘matching box’ or ‘boxing match’, referencing Rizal’s relationship with the juxtaposed other. Whereas, the rotating signage alternates between ‘RIZAL’ and ‘ALIZR’, a Hispanicisation of the Tagalog word ‘Alis’, and suggests a need ‘to leave’. Reamillo also builds on Rizal’s profession as an ophthalmologist, indicating notions of double vision, perception and perspective. The fictional self wears a monocle and along with other suggestions intentionally blurs the distinction between the two constructed identities.

The Rizal portrait on the matchbox is presented conventionally and framed by a wreath of honour, nonetheless in Ang Retabla Rizalista the modifications and adornments intentionally undermine and challenge the original reading. In place of Rizal’s partially cutout image Reamillo offers an image fragment from local beer ambivalently bestowed upon the hero’s image, along with his own parodying self. He also draws similarities between the constructed self and the hero, most notably the incorporation of Chinese silk referencing shared Chinese heritage. Still, what the viewer takes away from Ang Retabla Rizalista is not necessarily such subtle correspondences. Alwin Reamillo uses his self-image to explore the personal but moreover he applies this image to pose questions about the other – be this Rizal or the Philippines. The absent portrait exhorts the viewer to reconsider an all too familiar iconic image, and this absence replaced by a satirical and absurd presence helps the viewer to rethink the person, Jose Rizal, his life and contemporary legacy.

Christine Clark

Exhibitions Manager

National Portrait Gallery, Australia

1 Jose Rizal was tried for treason, sentenced to death and executed by firing squad. An important member of the colonial opposition, his words and image, particularly following his martyred death, became powerful symbols for liberation. Soon after the revolutionary Philippine Republic was beaten by American imperialism, statues of Rizal started to proliferate in the territory, commencing the ‘serialisation’ of Rizal. See Benedict Anderson, The Spectre of comparisons: Nationalism, Southeast Asia and the World, London & New York: Verso, 1998, pp. 49–51.

2 The retablo is the ornately decorated screen that stands behind the altar, forming the central point of any Catholic church. The literal translation of retablo is ‘behind the altar’ and is the Spanish word for ‘retable’.

3 The Filipino cultural predication, crab mentality, is akin to the Australian tall poppy syndrome – crabs in a container exhibit a tendency to pull each other down.

4 Alwin Reamillo, correspondence with the author, 1 June 2010