During 1970s he was a founding member of Gerakan Seni Rupa Baru (New Art Movement) and the Desember Hitam (Black December) movement. These were the first iterations of a vibrant contemporary art scene that embraced performance and installation as well as more traditional mediums, and encouraged strident political criticism at a time when expressing dissent became increasingly dangerous.

In the post-Reformasi era, after the fall of the Soeharto government, Harsono’s work has become more self-referential. He has engaged in a social research project, working directly with the Chinese-Indonesian community of his ancestry, documenting their stories on film. In 2010 the Singapore Art Museum held a major retrospective of his works from the 1970s to the present day. Harsono lives and works in Jakarta, travelling widely in Java for his research, and internationally.

Reclamation and reflection

FX Harsono’s four decade-long career underwent a fundamental shift in the early 2000s. The major catalysts for this movement were the tumultuous and traumatic events of Indonesia in 1998, including the May riots at the time of the downfall of the Soeharto regime, and the culture of violence that erupted immediately afterwards.1 This transitional period saw the brutal victimisation of many ethnic Chinese, a minority group to which Harsono belongs. Subsequent to these events Harsono’s artistic direction turned radically from a passionately held national socio-political position to centre on the self. This concentration on the self – an exploration of personally relevant history, meaning and expression through the self-image – continues to inform his practice.

This change in Harsono’s work was not necessarily comfortable at the outset. His political and socially motivated art was based on social awareness and the ideology of belonging and commonality – art was a mechanism to heighten awareness and support change for the entire community’s benefit. The events of the late 1990s, in particular violence against ethnic minorities, made Harsono question his national advocacy; as part of the Chinese minority coupled with being an Indonesian Catholic, he had been made to feel ‘not quite’ Indonesian. Underpinning his repositioning was the realisation that his feelings of displacement and alienation and the ensuing need to look at the personal had significance for his art, both on personal and communal levels. The early 2000s also saw the repeal of the ban on public expression of ‘Chineseness’, along with other restrictions, furthering his ability for personal exploration.2

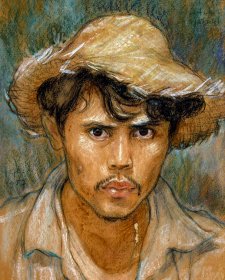

The two photo-etchings included in Beyond the Self are among the earliest works by Harsono that utilise the self-image. Created during a 2002–03 residency at the Amsterdam Graphics Atelier in the Netherlands, these works differ considerably in the denotation of the self.

Tubuhku adalah lahan (My body as a field 2002) is read immediately as conveying a more optimistic premise. With outstretched arms and head tilted backwards, the self portrait appears in the act of supplication or even complete surrender, or perhaps, in a state of renewal. The correspondence with religious imagery is reinforced by the knowledge of Harsono’s religious beliefs. The seeming incongruity between surrender and renewal can be appreciated in view of the artist’s personal repositioning and exploration of the self within an altered national landscape.

The personal body in Tubuhku adalah lahan is used as a field – employed as a vehicle, a site for expression. The self-image is surrounded by symbolic imagery, floating and at times superimposed, and lines denoting geometric divisions, a mix of easily interpreted and ambiguous symbols. There is the mandala overlaid with the lotus flower and references to Mother Earth and regrowth through images of rooted plants. The placement of the plants at the base of the artist’s head and above his open palms, seemingly mystically elevated, is particularly evocative, inviting reflection on life and educing thoughts of hope and potentiality.

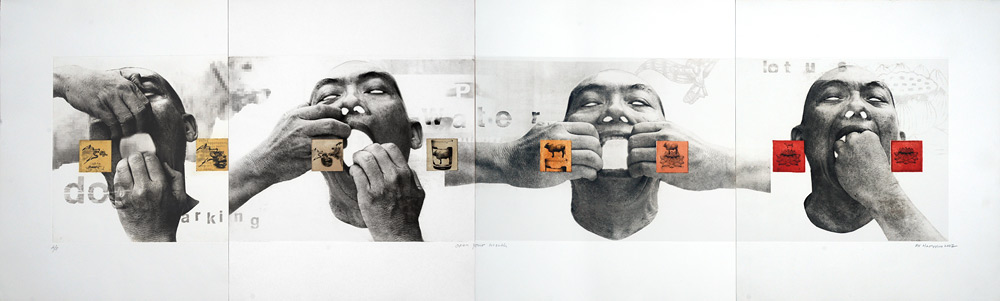

Open your mouth 2002 is more characteristic of Harsono’s oeuvre during this period. There is the use of multiples and the application of supplementary images and texts appropriated from mass media sources. Furthermore, the sense of angst in the work and its social comment on the prohibition of personal expression is more in line with other works from the period. The subject, presented with gaping mouth and white openings for orifices, appears digitally manipulated and is not immediately recognisable as the artist. The intentional ambiguity of the self portrait blurs the notion of identity as well as references the obscurity afforded by mass media comment, particularly the Internet.

From the mid 2000s Harsono repeatedly incorporated butterflies, and at times bees, pinned down with needles over his self-image. The creatures were systematically presented in multiples – reminiscent of scientific application. In some works the self-image becomes partly covered and speaks to the idea of absence, the feeling of being erased from one’s society and ultimately from one’s self. The act of applying needles and pinning down the multiple butterflies is also rich in metaphor: the act of piercing is violent and painful; the use of multiples blurs individuality; the allegorical use of the butterfly, a creature usually associated with carefree flight, transformation and freedom introduces a paradox.

Harsono’s newer body of self portraits explores personal and family narratives more directly. In the poignant 2009 performance video Rewriting the erased the artist is centrally positioned and shown writing repeatedly his Chinese name on sheets of paper, which eventually cover the entire floor. What is affecting is the obvious loss and intense demonstration of will; the awkwardness and the lack of calligraphic fluency is defied by the unreserved attempt to reclaim the lost past. Other works in the series incorporate family portraits alongside images of mass gravesites from past massacres of Chinese Indonesians.

Even while FX Harsono has turned toward to the self over the last decade, there remains a strong link to his work of the previous three decades, as he continues to give voice to the suffering of others, as well as himself.

Christine Clark

Exhibitions Manager

National Portrait Gallery, Australia

1 The 1998 May riotsoccurred in numerous locations in Indonesia but most notably in Jakarta. Triggered by economic problems (food shortages, mass unemployment, the collapse of the rupiah), the dates of May 13 and 14 are largely remembered for the pogrom targeting the properties and businesses owned by ethnic Chinese and the rapes and murders of citizens from this ethnic minority.

2 In 1967 President Soeharto banned the public expression of Chinese religion, beliefs and culture including the prohibition of Chinese characters. Former president Abdurrahman Wahid annulled the law in 2000.