He is also involved in KHOJ International, an organisation that works with artists, particularly in South Asia, encouraging creative dialogue, exchange and experimentation. Bhalla’s work often invites audiences to engage directly with otherwise overlooked elements of urban and metropolitan spaces, in particular water courses, in his home town, New Delhi, and those he visits during the course of international exhibitions and residencies.

Beyond the Self

Over the past ten years, Atul Bhalla has built up an impressive body of work that encompasses drawings, sculptures, videos, installations, performances and public interventions. Despite this formal versatility, however, he is best known for his photographs, most often presented as photo-series which create narratives that can be, in turn, enigmatic, poetic, lyrical, disturbing and visceral.

As all commentators note, his work, through its many media and moods, invokes water in one form or another: water flowing in rivers; water dripping from taps; water filling flush toilets; water drowning things placed in glass tanks; water packaged for sale; water running in sewers; water sucked out of the earth by electrical pumps; water given to the thirsty by water-carriers and good Samaritans; water washing the blood off his bloody hands; water enveloping his body as he sinks under the surface; water whispering to him from springs and streams long buried under the street.

What does this water mean, that flows so insistently through Bhalla’s work? Most considerations of Bhalla’s art discuss the eco-politics of water that his works touch upon: the appropriation, unequal distribution, commodification and pollution of water, especially as observed today from the ground of his own filthy megacity, Delhi; as well as a perhaps nostalgic evocation of another realm, of primeval rivers and cleansing rituals and a community of sharing, and of paying reverence to water’s life-giving force. All of these themes are present in Bhalla’s work, and it is right to identify them as his enduring preoccupations. For this reason, Bhalla’s work is generally spoken of as aligned with environmental activism – as his works make our callousness and wastefulness visible to our eyes.

But while the politics of water is Bhalla’s story, it is only part of his story. If there is conscientization in his work, there is poetry too; and if there are environmental concerns, there are also deeply personal elements in his work, which are hardly ever commented upon.

So it is another aspect of his work, so present and yet so little discussed, that I would like to turn to here: as the water laps against the artist’s body in work after work, I wish to turn to Bhalla’s inclusion of himself in so much of his work, and the meaning and the emotive weight of his performative presence.

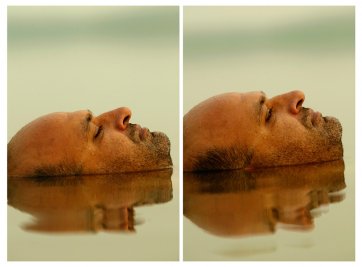

In recent years, photo or video-performance has become a prominent genre in contemporary Indian art. Well-known artists who put themselves in the frame – such as Pushpamala N, Nikhil Chopra, Shilpa Gupta, Sonia Khurana, Tejal Shah – don elaborate costumes, or strike highly wrought poses, to enact social roles or cultural tropes. Critics have dissected the meaning of their masquerades and of the selves they construct. Atul Bhalla is not placed within this frame. Yet most of his best known and most widely exhibited works are photographs and videos in which he is bodily present, and indeed, his face usually fills the frame. Consider, for instance, I was not waving but drowning II – a series of fourteen photographs in which he stands in the water unclothed, in profile and we see him slowly slip beneath the surface. His eyes are shut, the water is up to his shoulders. Now it is at his chin. Now his lips. Now his nose, now his eyes, now his brow. As he sinks under the surface we watch, fearful, but also soothed. This deliberate dropping into the water is a going forward that brooks no thought of a return; yet this melting-in, the liquid silk against the skin, this merging with the water, is wanted, desired: a beautiful immersion. In death, the river and me he fills the frame in all the sixty-three photographs: the camera moves around him, as a hand with a cut-throat razor shaves his passive head and his moustache, his beard and his hair fall away in a mourning ritual that follows a death. Tufts of hair fall on his naked shoulders, the razor moves across his throat. His eyes remain shut. And Mashk is a deeply moving video in which he slaughters a goat, to make a goatskin water-bag. The camera is fixed in a close-up on his face, which remains in profile, looking down. We do not see the hands that hold down the goat, or that wield the knife. Only his face, intent upon its task, showing no emotion. Yet, the moment the goat dies, we know: we know a life has been taken now through the merest flicker upon the artist-subject’s face.

While water remains a metaphor, Bhalla’s face and body are the crux of these works, yet his own role within them is unremarked upon. Is it because critics assume that male artists who do lens-based work are concerned with political issues and environmental crises; while female artists who use similar tools are usually held to be making the visual equivalent of confessional poetry?1 I believe something of this kind has happened to Atul Bhalla’s work.

Perhaps another reason Bhalla is not spoken of as a performance artist is because of the reticence of his presence. Unlike most other performers who face outward to address the viewer, his face is so often turned in profile; instead of engaging us, his eyes remain averted or shut. We do not watch Bhalla do anything,

become anyone; instead we watch him experience something. This is why the essential element in his portrayals are not the points of his eyes – which looking out at us, would have established his own selfhood, separate from us – but the expanse of his skin – which, laid bare, becomes a field for tactile sensations that we can feel along with him. Not an actor in these works, then: Bhalla’s body is landscape; a terrain in which elements come, to touch.

Khavita Singh

Associate Professor at the School of Arts and Aesthetics, Jawaharlal Nehru University

1 This kind of gendered reading makes it impossible to ‘see’ certain works in their entirety. And much as the work of many women artists is diminished when it is defined exclusively through their gender, and its politics is read as biography, the work of male artists too is leached of important qualities when it is overly masculinised in interpretation.