‘Finespun and impartial, the summer sunlight poured down prodigally on all creation alike’, wrote Japanese demigod Yukio Mishima, of the merciless glare of the sun which had gazed down with impunity as Hiroshima and Nagasaki were scorched by atomic bomb blasts. ‘The war ended,’ Mishima wrote, ‘yet the deep green weeds were lit exactly as before by the merciless light of noon, a clearly perceived hallucination stirring in a slight breeze; brushing the tips of the leaves with my fingers, I was astonished that they did not vanish at my touch.’ Mishima was deeply touched by a poignant feeling. ‘That same sun,’ he wrote, ‘as the days turned to months and the months to years, had become associated with a pervasive corruption and destruction.’ Here was pathos manifest in the very atmosphere, pathos matched by the author’s powerful, but conflicted, selfhood.

In Mishima’s 1963 short novel The sailor who fell from grace with the sea, adolescent boy Noburu reveres and resents his mother’s male lover, the sailor Ryuji. Ultimately Ryuji must be emasculated for failing to live up to the boy’s masculinist ideals – ‘what is beautiful must be strong, vivid, and brimming with energy’ – and yet all along Noburu feels a kind of love for Ryuji that tips into erotic fascination. Thus the tormented soul can only destroy what it desires. Similarly, ‘The alienated feeling that comes from psychological laws being crushed by the strange and shocking movements of the body’ is how Mishima described a 1959 performance of Tatsumi Hijikata’s Forbidden Colours in the newly-emergent dance-form of butoh. What pain to feel alienated from oneself!

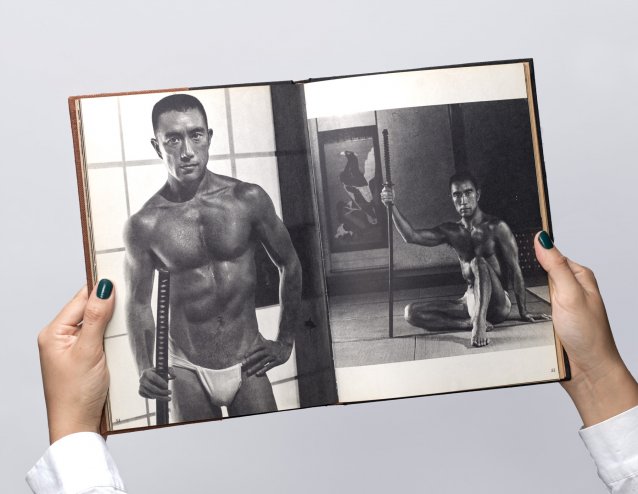

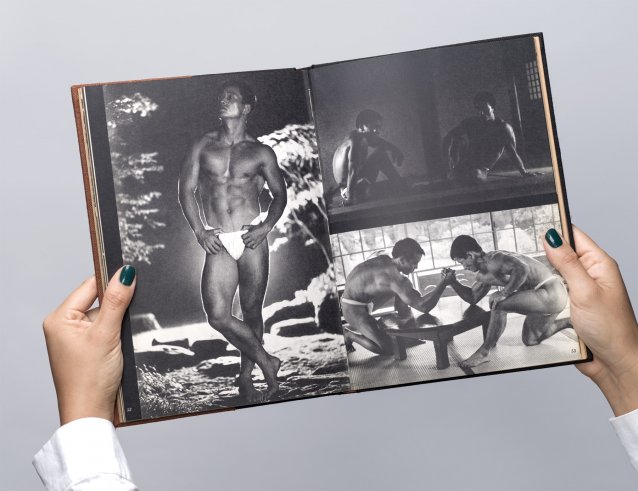

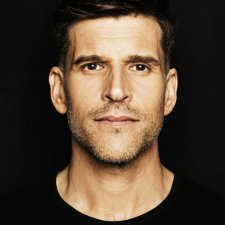

Mishima, always intellectual, and as a child anything but ‘rough-and-tumble’, set about transforming himself through bodybuilding. He gladly wrote the introduction to photographer Tamotsu Yato’s ground-breaking 1966 photo-book featuring a decade of the physical practice in modern Japan, Taidō: Nihon no bodibirudā-tachi (Bodybuilders of Japan). ‘In the past I wished in vain that there were an expert photographer of bodybuilders in Japan’, Mishima laments. ‘At last,’ he sighs, relieved, ‘with the appearance of this book, this long-felt wish of mine is answered.’ In 1955, at age 30, Mishima took up weightlifting. Yato photographed Mishima in 1965 (height 164cm, weight 70 kg). In Yato’s book Mishima’s body is stripped, save for the traditional Japanese fundoshi loin-cloth, and he holds a sheathed samurai sword as a prop. Steady gaze, poised relaxed stance – Mishima’s sweat-sheened torso declares flesh-and-blood presence. The shoji paper and wood door, the tatami straw floor mats, the wall-hanging scroll depicting an Edo-era falcon at rest combine to create the mise-en-scène.