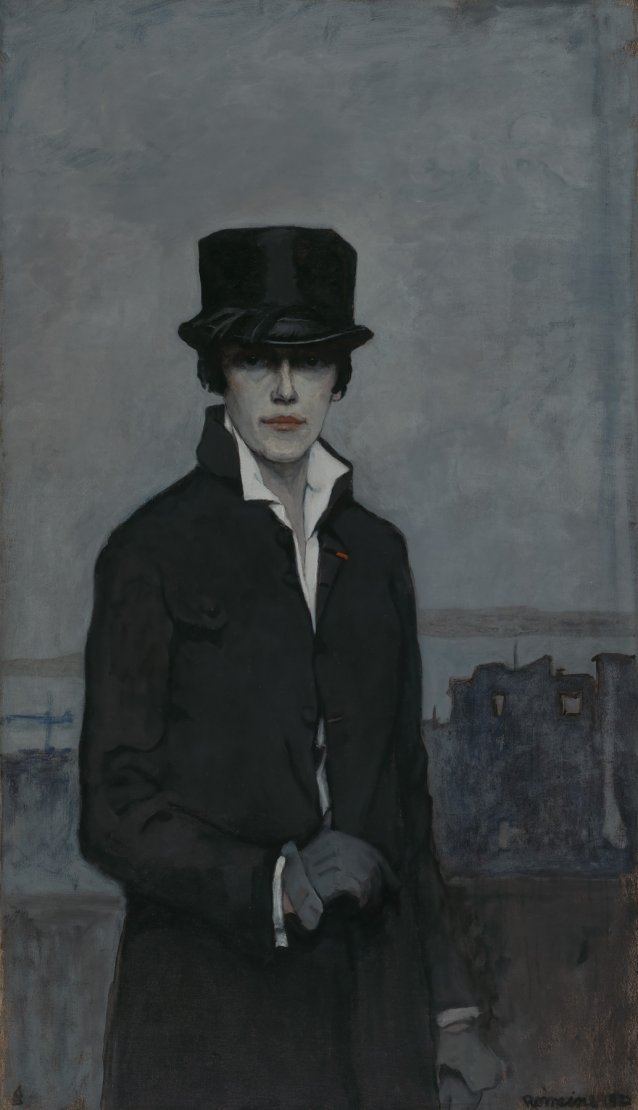

In the late 1990s when I commenced work at the Bendigo Art Gallery as Curator, I came across five paintings in the collection by Agnes Goodsir. I was particularly struck by two portraits, Girl on Couch (c. 1915) and Girl with Cigarette (c. 1925), and these were retrieved from the art store and included thereafter in the Australian permanent collection hang.

Both oil paintings intrigued me, and I found myself driven to discover more. The concept of uncovering the Goodsir biography had extra resonance owing to a chance encounter I’d had with her great niece, Mrs Anne Sheppard, in 1997. My subsequent introduction to the family meant I was exposed to unseen paintings, drawings and archival material, helping me to piece together the story of this expatriate artist, essentially forgotten at home, despite her work earning great acclaim overseas. The following year Bendigo Art Gallery held an exhibition of Goodsir’s work, In a picture land over the sea, with the show attracting unprecedented media attention and strong visitation.

Born in Portland in south-west Victoria in 1864, Goodsir lived a fairly conventional life for a woman in the period, painting still lifes initially before applying herself to the challenge of portraiture. During the late 19th century she studied at the Bendigo School of Mines in Victoria – hence her connection with the Bendigo Art Gallery – under the tutelage of the artist Arthur Woodward. With Woodward insisting that students be exposed to international cultural circles, Goodsir set her sights on Great Britain and France, venturing overseas to ‘find herself’ at the mature age of 36.

After studying at the Parisian academies of the day, her works featured in the seasonal salons, before she made her decision to move to London prior to the onset of the First World War. By all accounts she found shared lodging, connected with family, made a number of everlasting friendships and continued to paint and exhibit. Her painting Letter from the front was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1915, with the work later finding its way into the Bendigo collection, bearing the new title Girl on Couch.