‘We wonder how many people there are in London who have actually seen the National Portrait Gallery’, declared an article in the English illustrated magazine Once A Week in January 1862. ‘We question, indeed, if one man in a thousand knows where the effigies of England’s departed great are deposited,’ it continued, ‘for … the gallery is permitted to be open only three days in the week’, and was, in the opinion of the article’s author, so well concealed within a ‘private house’ in Westminster that ‘we have often been in the room for a couple of hours without hearing the echo of any footsteps but our own’. The author of the article meant no disrespect, and had not ‘dwelt upon the general deserted condition of this gallery gratuitously’. Rather, they wondered why an institution as august as a National Portrait Gallery, accommodated as it was then in suitably illustrious ‘apartments’ at 29 Great George Street SW1 (a stone’s throw from the Houses of Parliament and Westminster Abbey), had been trumped by certain windows on Regent Street and The Strand – said windows being the ones displaying the wares of notable creators of ‘sun limned portraits’. The answer to the question, the article claimed, was the carte de visite: the natty, diminutive variety of photographic portrait that, by 1862, had succeeded in upending portraiture – not least because of a group of likenesses taken two years earlier by the English photographer John Jabez Edwin Mayall.

Queen of cartes

by Joanna Gilmour, 22 May 2019

As reported by The Times in May 1860, Mayall had been ‘honoured by the Queen’s commands to attend at Buckingham Palace’ and ‘in the course of a morning very agreeably devoted to photography, produced a series of highly successful portraits of Her Majesty, his Royal Highness the Prince Consort’ and several of their children. Though hardly the first photographs taken of the royal family, they departed from convention in two key respects: not only had Her Majesty chosen to have herself documented in this humble, even déclassé format, but, more to the point, she had given her assent to the resultant portraits being published and made available for sale. To twenty-first century observers jaded by endless, banal images of royals and their progeny, there is probably nothing surprising about the world’s ‘first media monarch’, as the adage has it, being such an enthusiastic embracer of what is held to be the world’s first truly egalitarian form of portraiture. What might surprise, though, is the part played by Queen Victoria in influencing the uptake of the very thing that allowed photography to fully realise its democratic potential.

Patented in 1854 by the French photographer André Adolphe Eugène Disdéri, the carte de visite was originally conceived of as a livelier version of the calling card – the device by which those of an appropriate class might announce themselves to friends and associates, or signify a wish or an attempt to pay them a visit. Typically, this ‘new style of visiting card, on which is executed, with the most artistic taste and fidelity, a beautiful photographic portrait’ was roughly nine or ten centimetres high by five or six wide, and designed with collectability as well as portability in mind. In addition to their novelty factor, cartes de visite bore all of the traits that had made photographic forebears like the daguerreotype and the ambrotype so exciting, but in a concentrated, more user-friendly form. ‘Without disparagement to the performance of the miniature painter, we must record our veto against his works when brought as portraits into comparison with this flash-of-lightning method’, opined one observer of the daguerreotype in 1843. ‘Photographic portraiture depicts not merely the exactness of feature, so easily attainable by hand – it preserves the life and animation, the delicacy of expression, in fact so much of the character of the individual as is displayed in his features during the period of his sitting.’ Unlike daguerreotypes, though, cartes de visite were not one-off images but could be printed multiple times from a single negative, and thus were well within the means of average people. While George Baron Goodman, who is considered Australia’s first professional photographer, charged a guinea – one pound and one shilling – for one of his daguerreotypes in 1842, the artists who effected the carte de visite’s introduction to the colonies two decades later promised ten or more portraits for a similar fee. In May 1859, for example, the Sydney Morning Herald reported that cartes could be had from William Blackwood’s ‘Photographic Gallery’ on William Street for the ‘trifling sum’ of twelve shillings per dozen. ‘Truly this is producing portraits for the million’, the paragraph concluded prophetically. In addition, cartes were cannily marketed with a unique negative number, facilitating the ordering of multiple, potentially infinite copies at a future date. ‘Copies may be had at any time’ or ‘Orders by post executed with despatch’ were typical carte catch-cries, along with claims, occasionally thin or dubious, as to the artist’s accolades or status.

Perhaps more significantly, the carte de visite represented the complete antithesis of the idea of portraiture enshrined by the National Portrait Gallery and its ponderous assembly of painted canvas effigies held up as archetypes of ‘the true dignity of portrait painting’. By 1860, however – in large part due to photography – portraiture was no longer a matter purely of ‘art’ or taste, and had become increasingly available to a class of client for whom the ‘true dignity of portrait painting’ was secondary to the faithful, supposedly lowly, reproduction of a loved-one’s likeness. ‘Portraits … as photography now proves, belong to that class of facts wanted by numbers who know and care nothing about their value as works of art’, stated British writer and artist Elizabeth Eastlake in 1857 in pinpointing another primary factor consolidating the carte’s appeal. You might be no better than a tinker or a seamstress, yet the carte de visite, with its formulaic language of postures and props – ersatz classical columns and balustrades, patterned oilcloths, heavy drapes, painted backdrops – enabled you to present yourself as dignified and genteel, or possessed of other desirable characteristics. Photographers’ trade journals, furthermore, provided guidance as to ‘appropriate’ poses based on gender, age or profession, and which were likewise coded to project specific messages about the subject. The carte de visite thrived not just because it was cheap and nifty, but because (by virtue of its utility and ubiquity) it was able to forestall the idea that portraiture was a selective, exclusive activity, whether on the class or aesthetic fronts. In a fortuitous and mutually opportune way, Mayall’s photos – marketed as the Royal Album – set the carte-collecting mania in motion and helped facilitate the adoption of the practice of exchanging and cherishing portraits, whether of loved-ones and friends or of the famous and unattainable. At the same time, they allowed the Queen to show by example how agreeable, useful and respectable the photographic portrait could be – and, by implication, how much like every other wife and mother she was.

In various respects, then, there was nothing uncharacteristic about her invitation to Mayall in May 1860 ‘to attend at Buckingham Palace’, nor anything untoward in him being granted access to what must at first have had the feel of unvarnished, private scenes. The Lancashire-born photographer was already known to her and her husband, having exhibited many of his daguerreotypes in the Great Exhibition of 1851. Prince Albert was keenly interested in photography from its outset and in 1842, three years after the process was patented, he sat for a daguerreotype now considered the first photograph ever taken of a member of the British royal family. The Queen shared her husband’s enthusiasm and, as the mother of nine children, was alert to photography’s inventiveness and efficacy as a form of family record-keeping. It is believed, too, that Victoria’s rather lonely and confined childhood predisposed her to collecting photographic portraits as mementoes of relatives and friends.

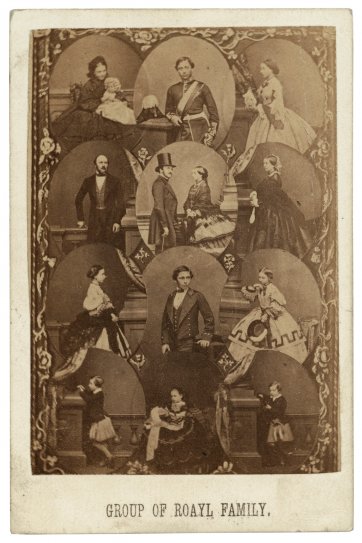

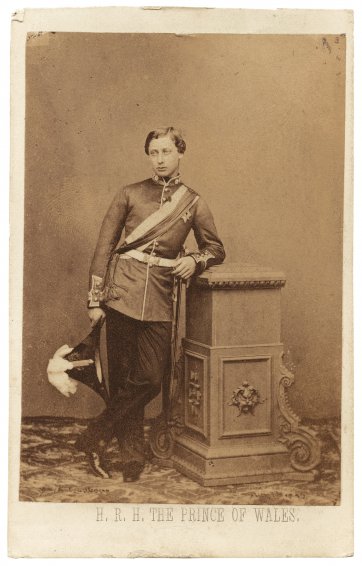

Correspondingly, in Mayall’s Royal Album photos, we have a pared-back, down-home Queen Victoria, not looking imperial or magisterial, nor portrayed as if she was channeling Aphrodite or Minerva or some other classical goddess. No crowns, orbs, thrones or jewel-encrusted maces, but ‘attired as plainly as any English lady could desire’, as one Australian account of Mayall’s photos put it. ‘The absence of the insignia of her Majesty’s regal office, although depriving the photographs of a certain amount of adventitious aide, renders them all the more truthful’, it concluded. Indeed, the same report bordered on insubordination by going on to describe the Queen as if she were a personal acquaintance, commenting that she ‘does not look quite so young as she did some decade of years ago’, and that she ‘would seem to have a decided tendency towards obesity’. In images from the series, Victoria and Albert look quizzically or devotedly at each other; and youngest daughter Princess Beatrice is doll-like in her ballerina kit. In another we see Princess Alice, aged about seventeen, looking suitably demure and marriageable, with eyes averted and an open book resting on her knee. Prince Arthur, a daisy in his lapel, has his arm around the shoulder of little brother Leopold, both of them dressed in matching kilts, socks and slippers. And eldest son Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, yet to acquire his weakness for gaming and actresses, appears an obedient, blameless youth. ‘These exquisite studies from the real life’, gushed Hobart’s Mercury in October 1860, ‘reproduce with a homely truth far more precious to the historian than any effort of a flattering court artist, the lineaments of the royal race.’ Sales of the Royal Album, consequently, went crazy, reportedly netting Mayall £35,000 initially and proving so popular that he was forced to neutralise photographic bootleggers by adding a signature to the plates from which later prints in the series were made. The Royal Album images and those by other photographers were frequently repurposed, paralleling the Queen and Prince Albert’s own habits of commissioning, acquiring and compiling photographs. As a result, the Royal Collection and the photographic holdings of museums such as NPG London are abundantly peppered with cartes by Mayall and his contemporaries, showing the family in groups, montages and compendiums, in pairs and individually, in both studio and actual settings.

Not only did Victoria’s reign parallel the advent and progress of photography, it commenced a time when faith in the empire’s leadership must have been at a low ebb, given the Regency period’s parade of philandering and/or profligate princes who had largely eschewed their patrilineal responsibilities. Up until her ascension in 1837, Victoria’s uncles and other aristocrats had supplied a rich lode of material for a ribald visual culture that gleefully lampooned members of the nobility as corpulent, debauched, dissipated or fatuous – or all of the above. Victoria and Albert, in contrast, were young, fetching and seemingly unsullied at the time of their nuptials in February 1840, and at last presented the prospect of monarchs who practised what conduct manuals preached. There was a great deal of interest in them too, in that they genuinely fancied each other – a characteristic somewhat atypical of marriages devised primarily with politics and pedigrees in mind. Victoria’s paternal grandmother, Princess Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, for example, was seventeen when she was fetched from a German abbey and briskly married off to George III, having been chosen for him from a shortlist of candidates. They met for the first time a mere six hours before their wedding in 1761. Though this match ultimately proved successful and productive in terms of heirs (and spares to boot), certain subsequent royal alliances were decidedly less so, particularly when it came to shoring up succession. Charlotte and George’s eldest son, later George IV married his cousin Princess Caroline of Brunswick, reluctantly, in 1795, mainly because he needed her dowry to pay his debts. He abandoned her soon after the birth of their daughter, Princess Charlotte – his only legitimate child among an unspecified number of ‘natural’ offspring. His brother the Duke of Clarence, later William IV, was likewise replete with issue, albeit those begotten of his partnership with the actress Dorothy Jordan and not of that with his wife, Queen Adelaide, who died childless. William and Adelaide’s marriage was another hastily-arranged one, the death of Princess Charlotte in 1817 underlining the necessity for George IV’s unmarried brothers to find fertile, acceptable wives. This was the catalyst for the marriage of Queen Victoria’s parents in 1818, her father Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn, being another of George III’s sons who’d had a child by his mistress.

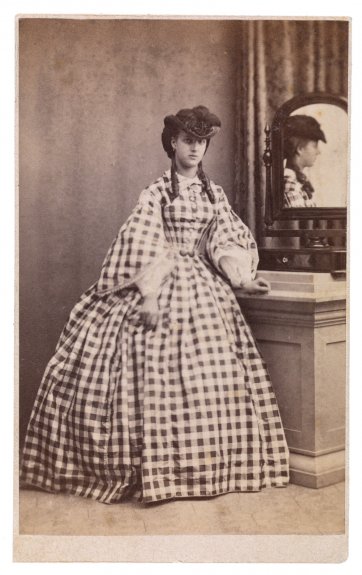

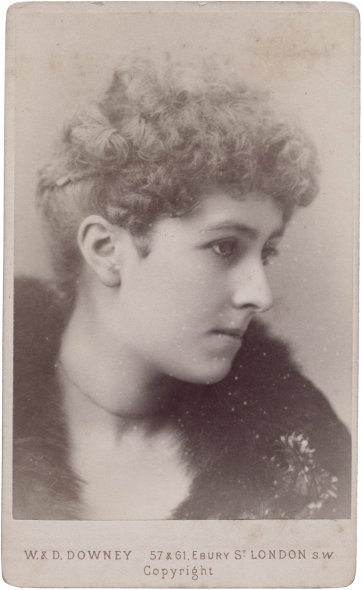

Victoria broke with this tradition by producing a daughter, Princess Victoria, an unimpeachable nine months after her marriage, and another eight children (four of them male) at regular intervals over the next seventeen years. The royal couple’s pride in having acquitted themselves so admirably in this matter might partly explain why the Queen sanctioned the creation of a suite of images for public consumption, the photographic portrait – and the carte de visite specifically – being an affordable, easily disseminated method of selling this respectability and relatability to the world. Subsequent members of the royal family also proved adept manipulators of their photographic image. Arguably one of the nineteenth century’s top-selling royal souvenirs, for example, was an 1868 carte by the London firm W&D Downey showing Alexandra, Princess of Wales – an accomplished amateur photographer herself – carrying her baby daughter on her back.

The disarmingly informal image was taken to demonstrate the Princess’ return to health following a complicated pregnancy. In hindsight it can also be read as an assertion of Alexandra’s dignity in the face of her husband’s barely concealed indiscretions with a series of lovers, among them socialites and lookers Lillie Langtry, Patsy Cornwallis West and, purportedly, Lady Randolph Churchill.

The first of these dalliances, involving an actress smuggled into his tent by army chums in Ireland in 1861, had in fact instigated the hunt for a bride for the future Edward VII (aka ‘Dirty Prince Bertie’), whose parents endorsed Alexandra after referring to cartes by a Copenhagen studio for verification of her reputed beauty. But the scholars who have written authoritatively on Victoria’s interest in photography concur that the many photographs of her and her family are just as likely to have come about through affection and sentiment, a love of collecting, and a strongly-held awareness of herself as an exemplar for womanhood and wifehood at home and abroad. One might argue that this consciousness of her influence found its apotheosis when Prince Albert died, aged only forty-two, in December 1861.

Thereafter, the carte de visite became the means by which Victoria cemented herself in the visual lexicon as the most stoic and noble of all widows, and a way by which the public could memorialise the lamented consort while also expressing sympathy for the bereaved queen. ‘No greater tribute to the memory of his late Royal Highness the Prince Consort could have been paid than the fact that within one week from his decease no less than 70,000 of his cartes de visite were ordered from the house of Marion & Co. of Regent Street’, it was reported. Throughout the 1860s, several London and European studios churned out prints of Her Majesty’s bereft, pudding-like person, clad in black crepe, face downcast, and in some images looking dolefully at portraits of her deceased husband. Conversely, subsequent photographs of Queen Victoria bely the popular assumption that the era named for her was straight-laced, monochrome and antithetical to women’s rights, demonstrating instead her position as the powerful, imperious head of a vast and complex realm. As with other collections wherein cartes de visite reside en masse, Victoria’s predilection for photography resulted in something which equates to a voluminous, multifaceted group portrait of the Victorian age: its politicians and rulers; its most celebrated artists and performers; its foremost scientists, writers and thinkers; but also the numerous, varied people she met and worked with, and those she was intrigued and amused by. Despite appearances to the contrary, it was Queen Victoria – and not her publicity-savvy descendants – who originated the art of harnessing photography in the service of her family’s global public image, while simultaneously confirming the photograph as the perfect means for gratifying our fascination for faces.

Related people

Related information

Portrait 62, Autumn 2019

Magazine

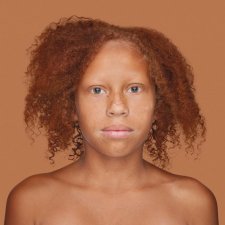

National Photographic Portrait Prize 2019, the iconoclastic Japanese figures Yukio Mishima and Tamotsu Yato, Angélica Dass’ Humanæ project and more.

Colour by numbers

Magazine article by Alistair McGhie

Alistair McGhie explores the many shades of Angélica Dass’ Humanæ project.

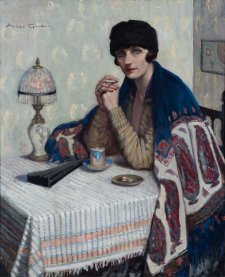

Agnes enigma

Magazine article by Karen Quinlan AM

Karen Quinlan considers the case of Agnes Goodsir, whose low profile in Australia belies her overseas acclaim.