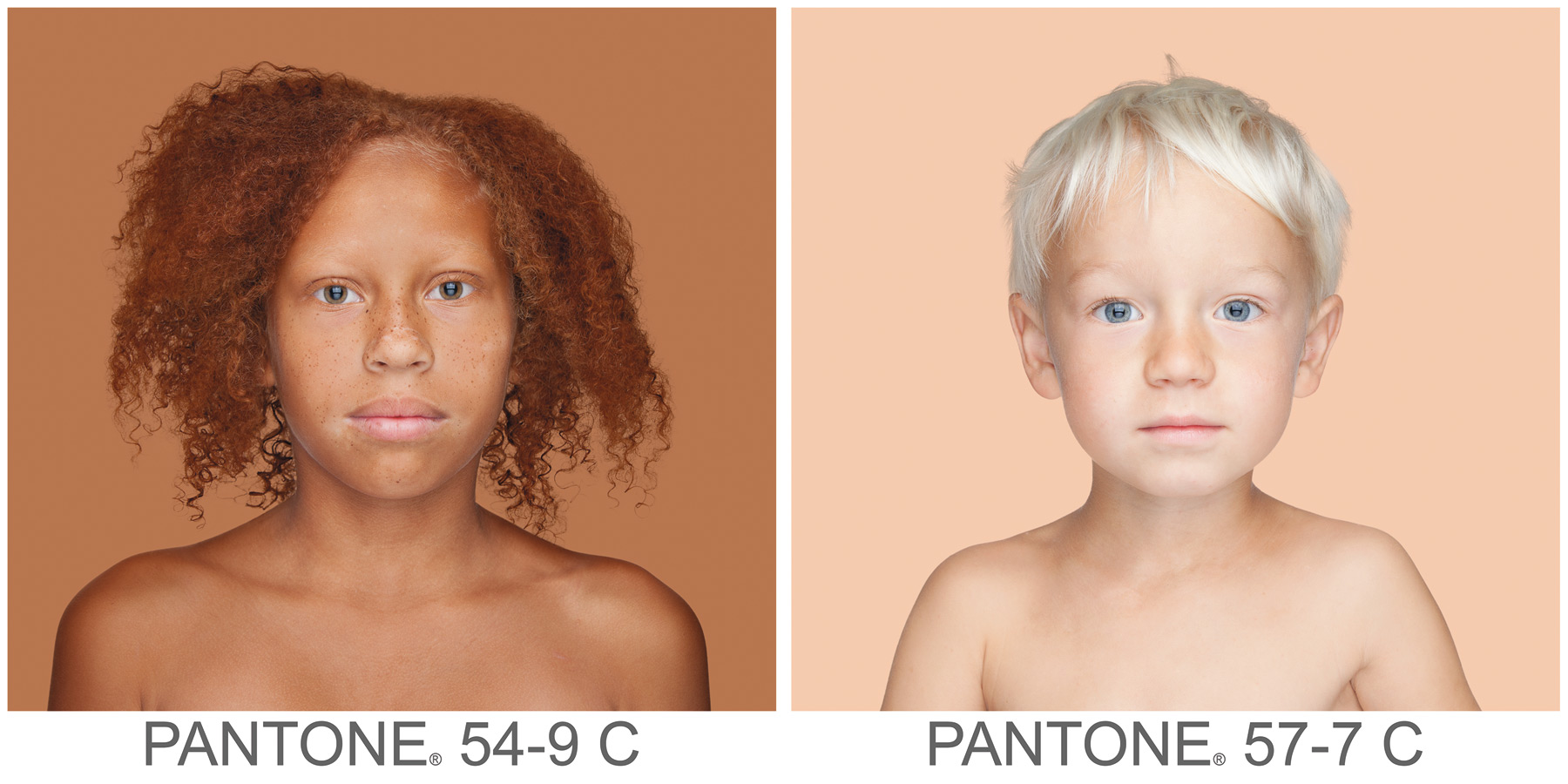

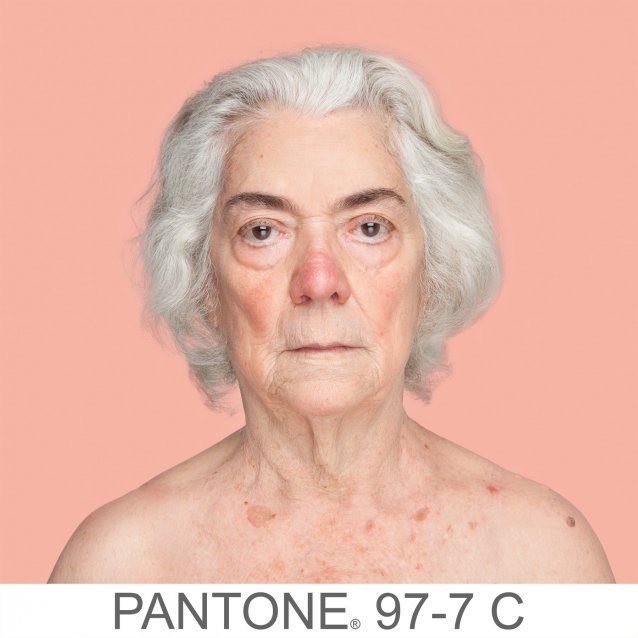

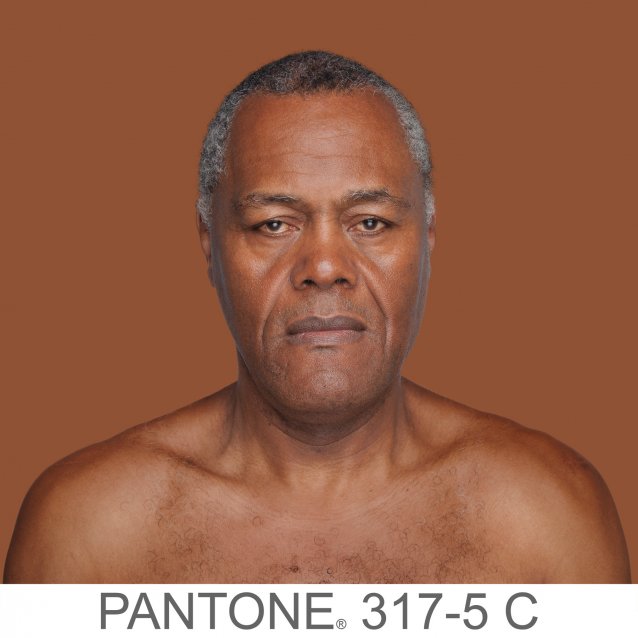

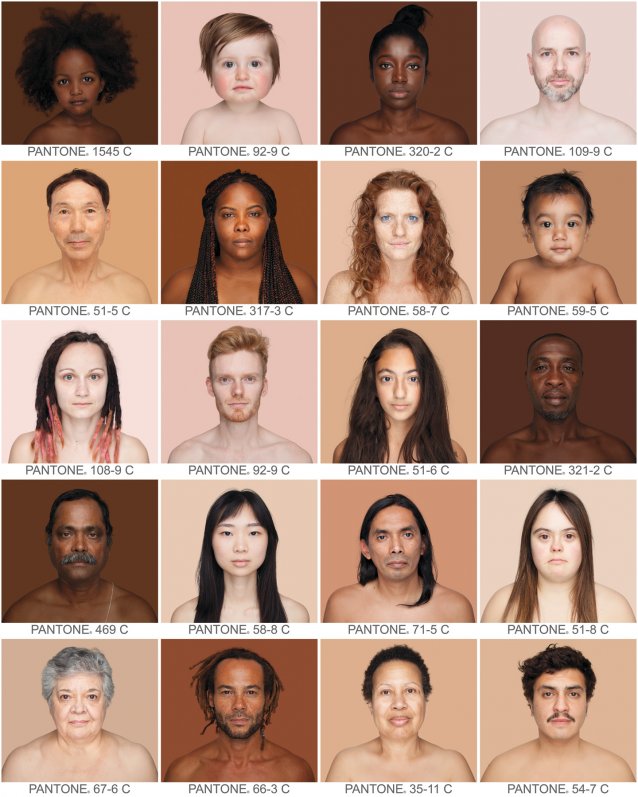

You may remember the 1980s and 90s advertising campaigns of Italian fashion brand Benetton. Oliviero Toscani was the photographer and art director behind those print and billboard ads featuring models of different nationalities dressed in extreme pastel combinations, as if protagonists plucked from a children’s flip-flap book, beneath the tagline ‘tutti i colori del mondo’ (all the colours of the world).

In 1990 that tagline morphed into ‘United Colors of Benetton’ – a line so good it’s still their trademark slogan today – but Benetton abandoned the colour blocking and polychrome skin tones and their ads became none-too-subtle allusions to social and political issues. At the time, Toscani’s work – such as a line-up of three indistinguishable human hearts overprinted respectively with the words ‘black’, ‘white’, ‘yellow’ – was controversial. Today they read as one-dimensional; all bark and no bite; race a device to sell clothes.