Judging a prize goes somewhat against the grain for me. I went to a school that didn’t have academic prizes (I have never been quite clear why; I suspect because it was deemed ‘unladylike’ for girls to compete against each other). I used to do aikido, one of the few martial arts that does not have competitions. I mostly do yoga these days and ‘winning’ at this is quite complex, though I haven’t given up. I’m highly competitive, but – or maybe because of that – I tend to avoid competing, because if you are competitive you always want to win. I wish either everyone could be a winner or no one. You could say my relationship with winning and losing is fraught. One of my favourite aspirational celebrity quotes is by Rainer Maria Rilke who said, in German of course, that the aim of life is to keep failing at greater and greater things.

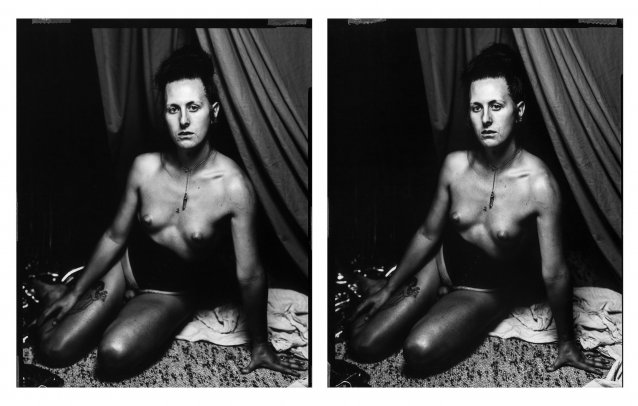

To be judged a winner by who, then, and by what criteria? When it comes to the National Photographic Portrait Prize, the Portrait Gallery’s recent panel-filling practice has been to include an internal staff member (this year – 2019 – Senior Curator Dr Christopher Chapman); a practising photo media artist (this year Melbourne-based Hoda Afshar, who won the prize in 2015); and a curator (this year me, Curator of Photography at the National Gallery of Australia). And by what criteria? Well, it’s a bit like yoga – a little opaque; not very cut and dried. How could it be? I can’t presume to talk for Chris or Hoda, but to get where we are as curators, practitioners and teachers, we’ve all acquired and honed very particular tastes and biases. It’s unavoidable. It’s a strength in many ways. You have to think a lot about image-making – read about it, talk about it, look at lots and lots of images, educate your eye and then rely on it. Trust it. You can’t perpetually doubt or second-guess yourself or you’ll go mad!