On the occasion of the National Portrait Gallery’s summer 2018-19 exhibition 20/20: Celebrating twenty years with twenty new portrait commissions, visitors were presented with an array of artistic approaches to portraiture, figurative and otherwise. The selection reflected the output of a variety of commissioned creators, from seasoned portrait painters skilled in rendering a realist ‘truth’, to photographers contemporary and commercial, with a bolt of new media for good (and cutting-edge) measure. Among the resulting score of works – all now part of the Gallery’s collection – two portraits are distinctive, not for their likeness or semblance of form, but for the visual narrative they present. They are the portraits of Australian literary greats Peter Goldsworthy, by Deidre But-Husaim, and Louis Nowra, by Imants Tillers.

Off grid

by Aimee Board, 22 May 2019

Both subjects are award-winning writers who continue to contribute rich layers to Australia’s literary landscape. Similarly, the artists who have created their portraits are masterful practitioners who have left an indelible imprint on this country’s art history.

The two works challenge what it is to depict a subject; their ‘truth’ may be found not in the realistic depiction of the sitter, but, rather, in the novel perspective at play for the viewer. Instead of the traditional engagement with a portrait subject – with proportions refined, telling glint in the eye and gaze cast towards the audience – the viewer is drawn into a more intriguing, participatory space.

Art historian Rosalind Krauss’ highly influential 1979 essay, ‘Grids’, provides interesting and instructive context for considering these works and the approach of their creators. Krauss posits that the grid in fine art may be experienced as ‘spatial’ or ‘temporal’ – the former concerned with the ‘within the grid’ system, with reference to the way a composition is mapped to the surface with realist technique; and the latter a ‘beyond the grid’ system, a more abstract approach concerned with time, memory and spatial dimensions beyond realistic representation.

The use of grids as a device in art is centuries old. Fourteenth and fifteenth century artists such as Paolo Uccello and Albrecht Dürer provided examples of masterly perspective with recourse to the device; it was their science of the real, with the grid used to transfer the three-dimensional aesthetic world to the surface of the canvas.

For example, Dürer’s 1498 Self portrait features a window opening to a distant landscape, a new world. Whilst his window is laden with greater symbolism, its structure and shape functions as an armature of the composition within.

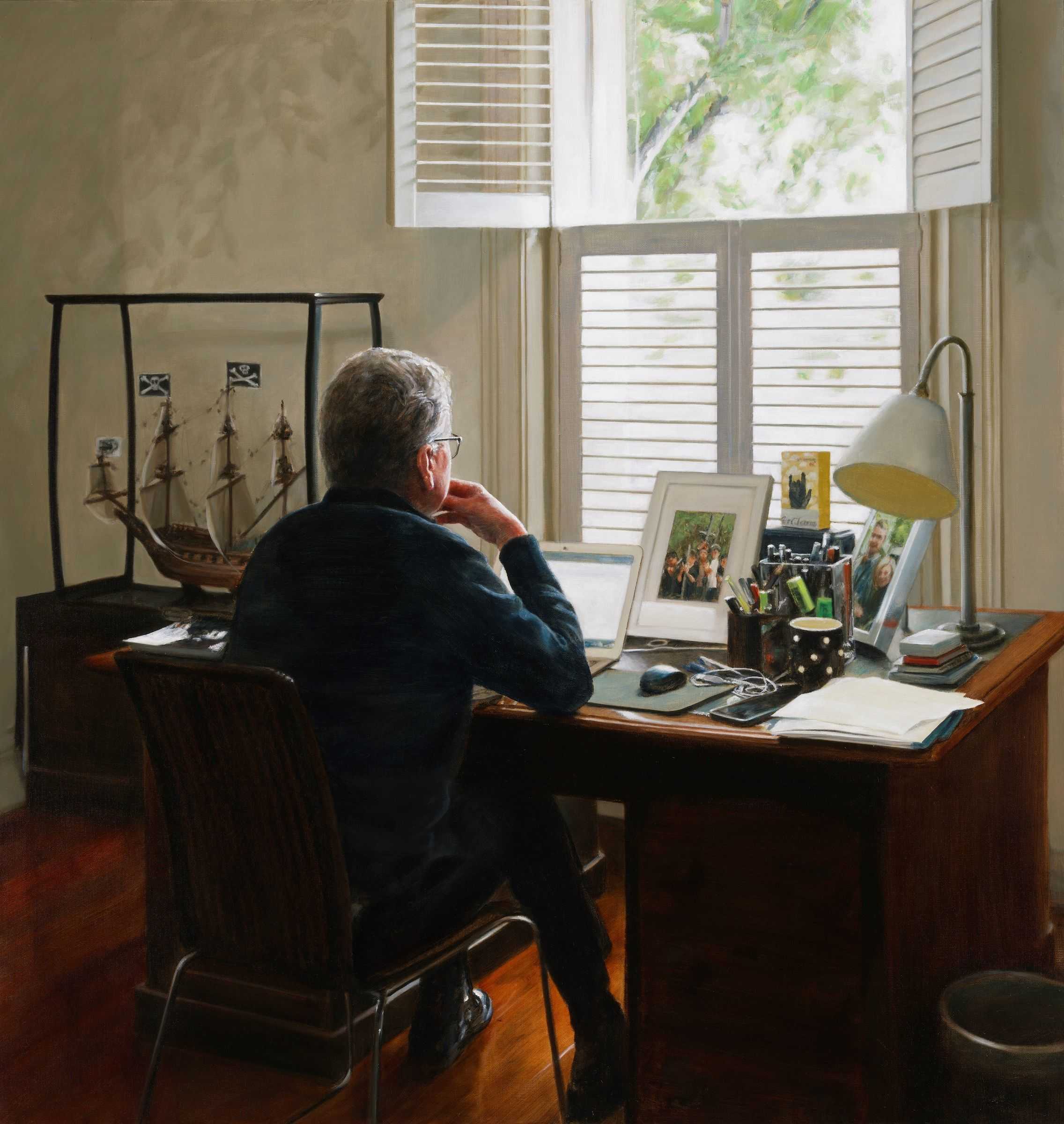

In Deidre But-Husaim’s portrait of Peter Goldsworthy, the artist’s grid underpins a composition that cleverly funnels the viewer’s eye, in Krauss’ terms, both ‘within’ and ‘beyond’. Entering the frame, the viewer plays voyeur as we witness the writer at work – observing over the shoulder as though a character entering the scene of a story. Detailed scenery either side of the subject provides the setting – the back-story – while the main character sits poised, waiting for inspiration to strike, to unleash. Perhaps Goldsworthy is journeying as a passenger (or commander) of the Dutch merchant vessel Batavia, on the subject’s left. A token of his 2001 opera libretti of the same name, the ship model is adorned with miniature pirate flags made by his grandchildren, who are pictured in the frame to the right of the subject.

Above the figure, the open and closed tiered shutters emphasise the structured, grid-like space within the frame, while also providing the viewer a portal into the narrative, mythical space beyond it. Krauss speaks of the grid’s mythic power to make us believe we are dealing with the material – the scientific, logical world – while also providing access to one’s own beliefs – the imagined, fictive space. But-Husaim achieves this parallel between the material within-the-frame and mythical beyond-the-frame notions, with the positioning of the subject with open shutters overhead, light funnelling from darkness to light, in effect transporting the viewer from the material world to the illumined realm of the mind beyond. Of the work, But-Husaim notes ‘the window faces south and there was a beautiful light coming in. As I sat in the room observing [Goldsworthy] in his natural, unposed position, I liked the idea that nothing’s resolved and wanted to capture a sense of that. The ambiguous shadow space in the top left of the image alludes to the unrealised potential of possibilities, ideas that are as yet unformed.’

Just as a writer’s words must be read by an audience for a narrative to be made vivid, the very act of the viewer observing Goldsworthy looking beyond the frame for inspiration signifies the subject’s essence, reflecting the author’s unique ability to transport his readers.

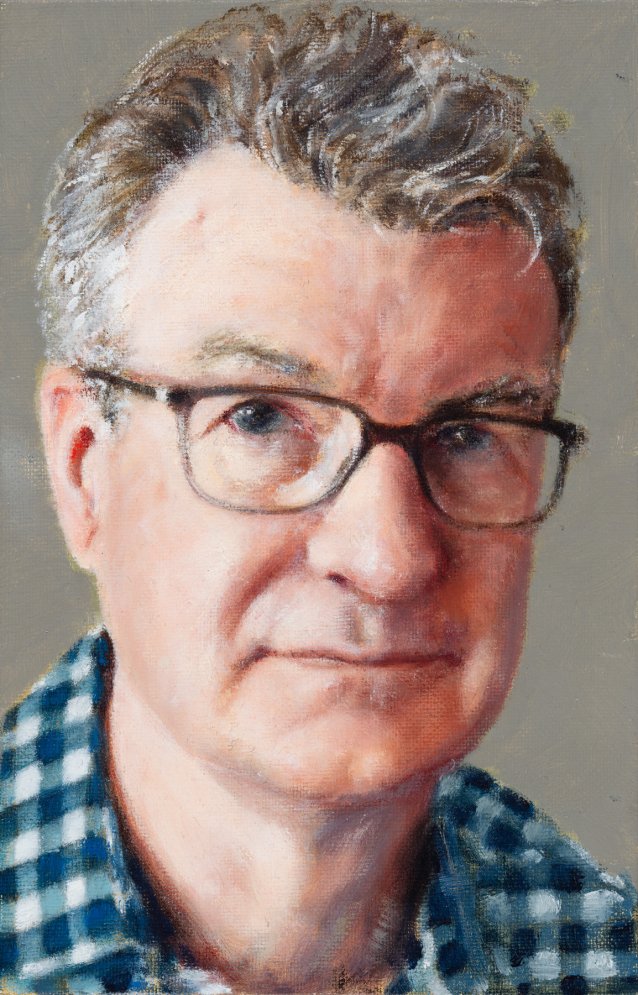

But-Husaim had different plans for the portrait in the first instance. Referring to her study of Goldsworthy’s face, she explained ‘I didn’t plan to paint Peter from the back. I painted the portrait as a starting point to get to know him a bit. It’s interesting that we’re privy to this intimate thing that they’re writing, but we actually know very little about the authors.’ These themes of anonymity and the unknown subject appear elsewhere in But-Husaim’s work, with her interest in the viewer as active participant, and pathways of meaning also consistently explored. In her painting The Statues (2015), the viewer observes her anonymous subjects as they gaze curiously at artworks in a gallery space; we become enmeshed in their transported state. There are multiple reflective and translucent surfaces, again providing a tunnel for the viewer into the illusory space beyond.

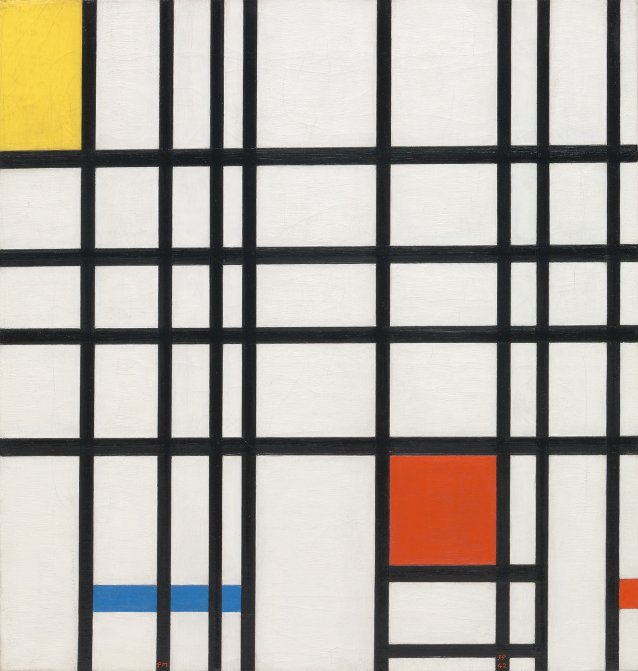

Krauss applied the notion of the temporal space beyond the frame to artists of the twentieth century who challenged the objective world, deconstructing the classical and questioning the material. They – the dadaists, surrealists and minimalists, among others – all viewed the grid as their staircase to the universal; the grid’s lattice became an instrument of being, mind and spirit. The iconic Piet Mondrian, for example, upon abandoning the figurative, produced minimalist geometric forms to depict the rhythm and pulse of modern life. Accordingly, his Composition with Red, Yellow and Blue, c.1937-42, ostensibly a black geometric pattern with a smattering of primary colours, is equally an interplay of oscillating planes signifying moods dancing within.

Since the early 1980s, towering figure of Australian art Imants Tillers has utilised canvasboards placed together in a grid-like structure to probe the presence and absence of self. His painting, Diaspora (1992), a narrative response to the political events in his parents’ homeland of Latvia in 1990 and an exploration of his familial cultural heritage, is presented on 288 canvasboards. The motifs and matter dispersed across its surface represent the mutability of self, always transforming and in a state of becoming. There is almost an implied sense of motion and temporality within the work. In relation to the artist’s personal journey, growing up as a child of refugees, the text and imagery taps into Tillers’ sense of ambivalence, both in relation to his parents’ past – their trauma at having to leave loved ones and their homeland – and the complex duality of his cultural origins.

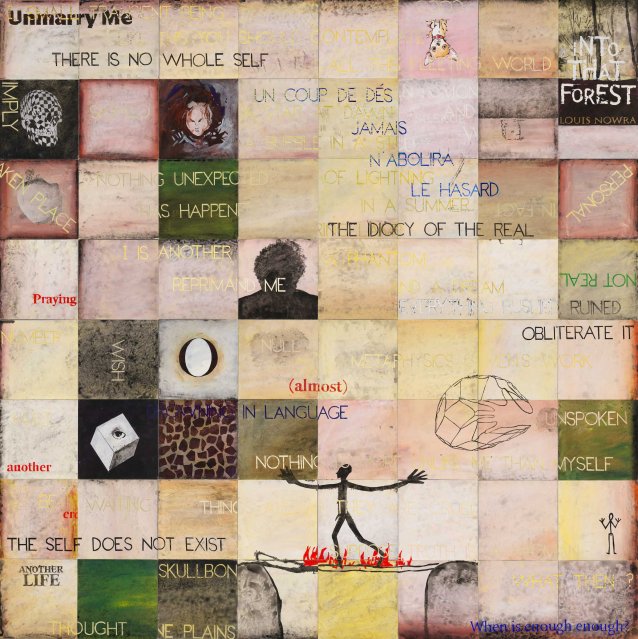

Similarly, in the portrait of Louis Nowra that featured in the 20/20 exhibition, Tillers positions motifs, images and text in flux to communicate aspects of his subject’s character and the complexity of his life journey. In keeping with Krauss’ modernist ‘myth’ – the idea of a mythical, narrative space beyond the frame – the viewer traverses a symbolic staircase, a lattice-like structure in which signifiers and fragmented meanings have been intuitively placed.

Speaking on his use of text in the portrait, Tillers notes, ‘it’s kind of a meditation on identity and reflecting on what a person actually is beyond their physical kind of appearance ... I had read several of his books including Chihuahuas, Women and Me, a fantastic collection of reflective essays on the likes of Christy Canyon the porn star, to Chateaubriand the famous French writer. The text in the portrait is reflective of his life and range of interests.’ He also points out, ‘it engages the viewer more than just an image, because you stop to read a text, and then wonder what it means. So it’s a way of actually slowing down the viewer’s response, rather than just looking at the image and recognising whoever.’

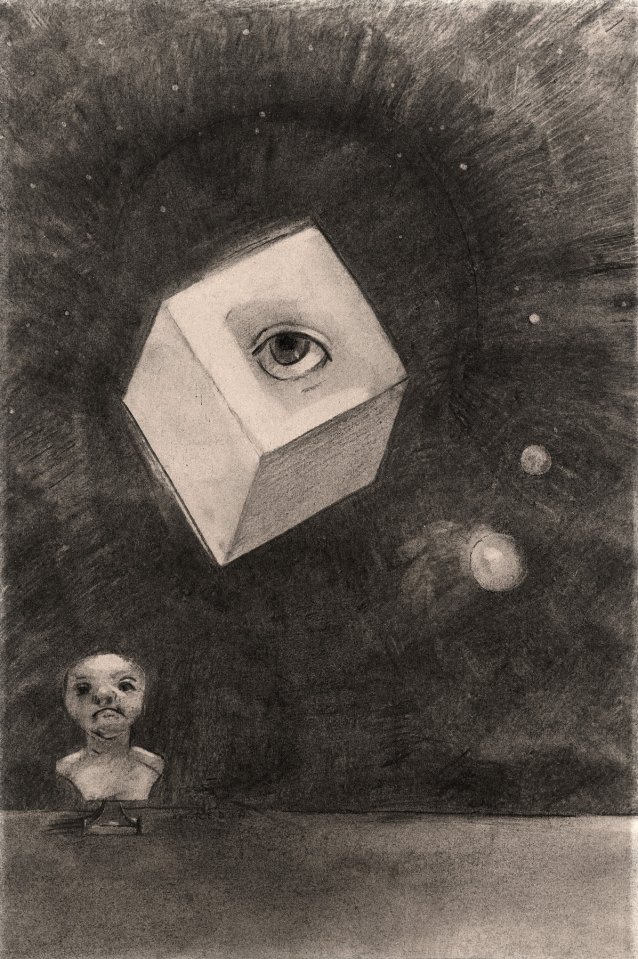

Exploring the idea of the grid within Nowra’s portrait, ‘beyond’ the sequence of square panels, we see a cube with eye peering out at the viewer – a motif from Odilon Redon’s charcoal drawing, Le cube (1880) – along with a human skull with grid stretched over it, inspired by an image from Mexican contemporary artist Gabriel Orozco that the artist liked for its peculiar nature. The inclusion of these mysterious motifs may be read both as existential signs for personal reflection and providing context for Nowra’s life experiences. The motifs, then, are elements ‘beyond’ both the subject and frame. Similarly, Nowra’s storytelling includes characters displaying the writer’s traits, in tales based on the anomalous events in his life. As Tillers notes ‘truth is actually stranger than fiction. And Louis’ autobiography ... you couldn’t actually invent a fiction like that and yet that’s what happened to him.’

It was a troubled childhood, to put it mildly. In his 1999 memoir, The Twelfth of Never, Nowra relates unimaginable stories. In one, a young Louis watches on as his granny jabs at a bonfire with a rake, ‘her eyes mesmerised by the rainbow showers of sparks and flames … Everything that had been in my suitcase was on fire, as were some of her nylon and rayon clothes that were shrivelling and melting in the heat.’ In his portrait we see a possible reference to the tale, with a stick figure Nowra, arms outstretched, traversing a flame-lit wire.

Tillers explains ‘after meeting Louis and reading several of his books, my suspicions were confirmed and I realised that he truly was fearless in his life and work, and this is what I wanted, above all, to portray’. The figure’s form came about via a discussion between Tillers and Nowra and their mutual friend and author, Murray Bail, who asked Nowra how Tillers should paint him. ‘He’s painting me as a stick figure’ came the quipped response. Taking this on board, Tillers included a stick figure without its facial features. Nowra had earlier commented to Tillers that he was not a fan of the formal portrait, suggesting that he could paint the back view of him.

Tillers notes, ‘there is also a literal image of Louis in the painting which is kind of a back view… there’s a bit of chance in my work and when I painted the silhouette of him, it looked like a view of him from behind.’ The resultant portrait, as Louis and his wife Mandy Sayers said to Tillers, is ‘a mental picture rather than a literal one’, consistent with the concept of portraiture beyond the frame.

As portraits that communicate both within and beyond their frames, these two new works by Deidre But-Husaim and Imants Tillers add to the Gallery’s growing number of non-representational portraits. The paintings communicate more than the subject’s features; they explore aspects of their identities, inviting observers to engage in a more involved and nuanced way, revealing inner truths for both artist and viewer alike.

Related information

20/20

Celebrating twenty years with twenty new portrait commissions

Previous exhibition, 201820/20 showcases the dynamic suite of new portraits commissioned to celebrate the National Portrait Gallery’s 20th year. Leaders and individualists invited by the Gallery were matched with unique artists to create distinctive contemporary portraits.

Portrait 62, Autumn 2019

Magazine

National Photographic Portrait Prize 2019, the iconoclastic Japanese figures Yukio Mishima and Tamotsu Yato, Angélica Dass’ Humanæ project and more.

Petal to the mettle

Magazine article by Dr Sarah Engledow

Sarah Engledow lauds the very civil service of Dame Helen Blaxland.