If you have the good fortune to find yourself in London this season, as I had in the last week of November 2018, you may seize the opportunity to spend a little time with an unexpected highlight of the Royal Collection Trust’s current exhibition Russia, Royalty and the Romanovs in The Queen’s Gallery at Buckingham Palace. You rarely get close enough to this magnificent portrait of the soigné Karl Robert, Count Nesselrode (Tsar Alexander I’s Foreign Minister at the Congress of Vienna), 1818, by Sir Thomas Lawrence. That is because it’s almost always ‘skied’ in the Waterloo Chamber at Windsor Castle. It is also overshadowed there anyway by the much larger full-lengths, all by Lawrence, of far heavier-hitters such as the Tsar, Pope Pius VII, the Duke of Wellington, Field Marshal von Blücher & Co. Quite obviously Lawrence was at the top of his game. He was such a brilliant heir to Reynolds and Gainsborough, but still, I think, a relatively and inexplicably under-appreciated painter. He was a master, above all else, of breathtaking passages of carefully differentiated blacks: black velvet as against black fur, as against black lawn cloth, as against silk hose, and so on, each texture announcing itself with perfect clarity but within an astonishingly narrow tonal and chromatic range. His was an almost miraculous technique. Count Nesselrode has not even the hint of a crack or fissure. The paint film is as fresh as the day it was hoisted into place at Windsor.

The Lawrence lustre

by Angus Trumble, 21 January 2019

Eighteenth and nineteenth-century British artists specialised in weird childhoods. William Hogarth’s father ended up as a debtor in the Fleet prison after his ill-conceived coffee-house went under. Allan Ramsay’s father and namesake in Edinburgh was a cultivated but slightly impractical poet. Thomas Gainsborough’s was a clothier, who also lost everything, and reinvented himself as the local postmaster in Sudbury in Suffolk. Sir Joshua Reynolds’ was a fellow of Balliol; Joseph Wright of Derby’s an attorney; William Blake’s a London hosier; and JMW Turner’s a wig maker and barber of Covent Garden (from whom he was separated early). In every case, intriguing questions arise from the artist’s professional life as to the impact and residue of each of these experiences of Georgian childhood. But for sheer colour, Sir Thomas Lawrence’s upbringing trumps them all.

As a supervisor of excise, Thomas Lawrence senior was the importunate, careless, impatient, under-paid, determined, but not particularly successful pursuer of smugglers in Devon. Abandoning excise, he went into hospitality. He amalgamated the American Coffee House in Bristol with the White Lion Hotel, a failure. He was fond of books, poetry, music and art. Mrs Lawrence, Lucy, was the niece of a judge and, encountering her in 1780 when Lucy was chatelaine of an inn, Fanny Burney thought she was ‘above her station’. In sharp contrast to her husband, Lucy Lawrence was from time to time good with money, and when the family moved from Bristol to the Black Bear Inn at Devizes in Wiltshire, the new business became a convenient and unexpectedly comfortable, respectable, and above all enjoyable stop on the road from London to Bath. The Lawrences’ youngest surviving son Tommy was beautiful and versatile – a prodigy, a sort of gold mine – producing likenesses and drawings after the Old Masters and, with equally precocious talent, reciting Shakespeare and Milton, all for the amusement of the guests.

David and Eva Garrick wondered if young Tommy would gravitate towards the stage or the pencil; both seemed entirely feasible. Fanny Burney (visiting with Mrs Thrale) described him as ‘the wonder of the family [...] a most lovely boy of ten years of age’. She was still writing about him long after he died. Lucy Lawrence boasted that Sir Joshua Reynolds had pronounced Tommy ‘the most promising genius he had ever encountered’. Through Mr Lawrence’s negligence, however, the Black Bear went under, and the family rather sensibly moved to Bath. There, aged fourteen, Tommy first saw Mrs Siddons – years before he became romantically but enigmatically ‘entangled’ with her daughters, Sally and Maria – and learned to work in pastel, churning out half-length portraits which sold for three guineas, ‘at that time for Bath a very extraordinary sum’.

Eventually Lawrence needed to go to London. It was an obvious step that his father and mother, brothers and sisters clearly dreaded, but beyond 1787 it could not be delayed any longer. After a brief period at the Royal Academy Schools, in which he obviously outshone his contemporaries for sheer brilliance, in 1789 he was summoned to Windsor to paint Queen Charlotte and Princess Amelia. The following year for the first time he showed an impressive group of pictures at the Academy, including his portrait of the Queen, and in 1792, after Reynolds died, the king immediately appointed Lawrence painter-in-ordinary. He was barely 23.

Two years later, at the earliest permissible moment, he was elected a full academician, thereby ruffling some much older, well-connected plumage. In the meantime, his portrait practice flourished, and its roots found nourishment at the highest social altitudes, to which Lawrence ascended nimbly, without the aid of oxygen. He never had any difficulty attracting grand patrons. But Lawrence’s personal life, buoyed by growing extravagance; the enjoyment of servants; intimate friendships with married women (including Mrs Wolff, the wife of the Danish consul); a distaste for the inconvenient, humdrum business of domestic life; and, above all, the passion of collecting Old Master drawings, gradually descended into the frightening chaos of insuperable debt, from which he never escaped. Although his order book was full, and a queue of notables stretched out his front door in Soho and a considerable distance down Greek Street, at first watched with glee by his proud but ailing parents, who came to live with Lawrence until they both died in 1797, ten years later he was shocked to discover that he owed £20,000.

Perhaps for these reasons – though much earlier Thomas Gainsborough had felt exactly the same way for different ones – in due course Lawrence felt wholly trapped by the genre of portraiture in which he was so dazzlingly proficient, ‘shackled,’ as he put it, ‘into this dry mill-horse business’. On the bright side, in 1810, when his nearest rival John Hoppner died, he was able to increase his fee for a full-length portrait from 200 to 400 guineas, a very large sum indeed. After a long period in which he was shunned by the Prince Regent, probably because he worked for the by then wholly estranged Princess of Wales, Lawrence managed, through the future Marquess of Londonderry, Lord Castlereagh’s half-brother, to return to Court. Thence he was sent to execute for the Regent an ambitious series of full-length and other portraits of the allied sovereigns and statesmen of Europe, including Count Nesselrode, whose only shared interest was victory over Napoleon. The group was destined for the Waterloo Chamber at Windsor Castle, and included among others the Tsar, the King of Prussia, the Emperor of Austria, and the Pope (whose ankles and pontifical shoes obviously fascinated Lawrence, always alert to the sumptuousness of silk plush, velvet, rich scarlet, and the telling detail). To create these pictures, the Prince Regent armed Lawrence with a knighthood and expenses. He went first to Paris in 1815, then between 1818 and 1820 to Aix-la-Chapelle, and on to Vienna, Rome, and back via Florence, Parma and Venice. He attracted the interest not merely of the great and the good generally, but of no less a statesman than Metternich. And these quasi-diplomatic art missions to the courts of continental Europe propelled Lawrence into a stratospheric rank that was comparable only with that of Peter Paul Rubens.

Upon his return to England, Lawrence was elected, nearly unanimously, to succeed West as third President of the Royal Academy. In the last ten years of his life, he showed no signs of slackening, tiring, or resorting to rote-learned formulas. Indeed, his late portraits, particularly those that he executed for his new political patron Sir Robert Peel, are among his most inventive, thoughtful, high-octane, ravishing. He died suddenly in 1830 at home at 65 Russell Square, in the company of his valet Jean Duts, whose tenderness, loyalty and care he had earlier praised to another of his devoted female friends, Miss Croft.

There is so much in Lawrence’s finest portraits that gives pleasure, above all, I think, his ingenious treatment of hands. Look at the contrast between the attitude of the Tsar at Windsor, his royally gloved hands clasped nervously in front, and the magnificent attitude of Blücher’s, the left clasping the hilt of his sword, the right extended in a gesture of command worthy, if not of Moses, then at the very least of Marcus Aurelius. If Sir Thomas Lawrence remains, perhaps, the least lionised figure in the current pantheon of England’s greatest painters, he is to me in many respects the most attractive, the most lovable, and definitely the best dressed.

Related information

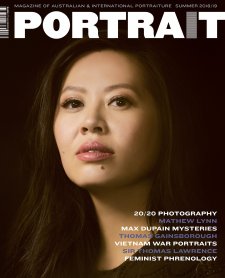

Portrait 61, Summer 2018/19

Magazine

Max Dupain's unknown portrait subjects, phrenologist Madame Sibly, Indigenous-European relationships, Thomas Gainsborough and more.

The jungle look

Magazine article by David Gist

David Gist steps beyond the public relations veneer of Australia’s official Vietnam War portrait photographs.

The Gallery

Visit us, learn with us, support us or work with us! Here’s a range of information about planning your visit, our history and more!