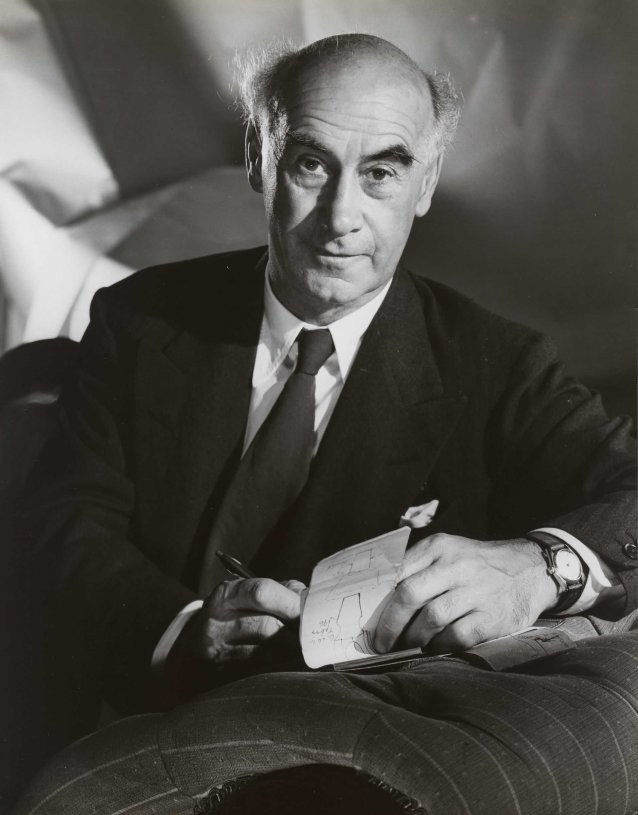

Nestled safely in the basement stores of the National Portrait Gallery lies a box containing 30 photographs by Max Dupain. They form part of a larger private collection of vintage prints by the iconic Australian photographer from which the Gallery has judiciously been acquiring works. (As of December 2018, the Portrait Gallery Collection features some 85 Dupain photographs.) The portraits in the box are diverse. Some are formal commercial headshots, such as that of an avuncular, bespectacled man in a suit who confidently leans into a closely cropped frame; Dupain has captured the man’s amiable expression with refreshing frankness. Others are more unusual – in one, a bearded man stares directly at the camera as he sits in front of an astrological dial; his right hand emerges from a foreground shadow, clutching what appears to be a hypnotist’s pendant. The group forms a disparate group of photographs, bonded in the first instance by one stark fact: the sitters were all unknown. In order to determine the identities of these mystery portraits, I embarked on a research journey that led me into the heart of Dupain’s portraiture oeuvre, and revealed fascinating stories of life in twentieth century Australia.

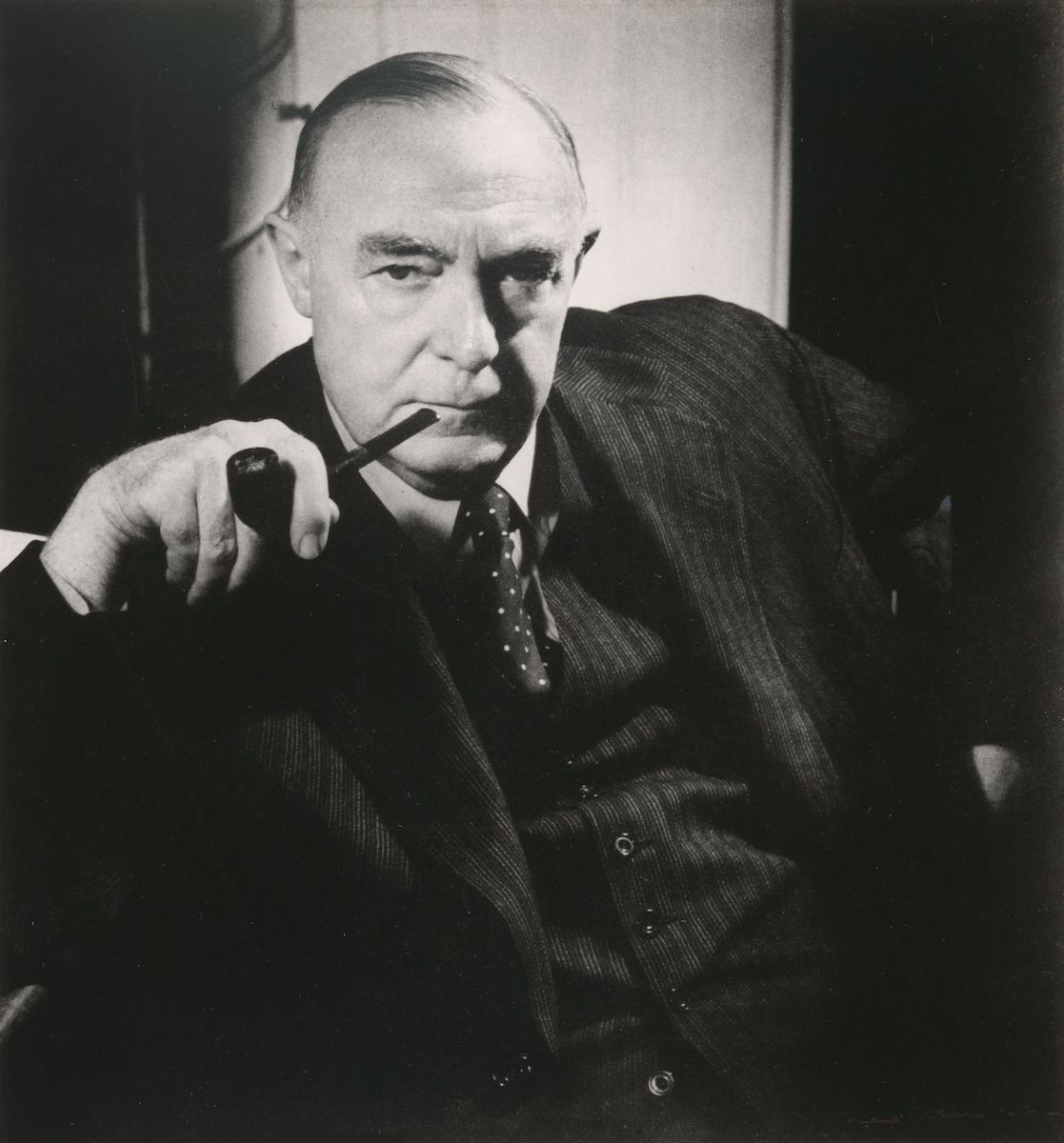

One of the largest groups of portraits by Dupain appears in periodicals from the late 1930s and early 1940s. Patronised by the stylish publisher Sydney Ure Smith – whose 1948 portrait by the photographer (captured with grave countenance and pipe clasped tight) is part of the Gallery’s collection – Dupain gained widespread recognition for his published work, especially his photographs in The Home magazine. I began my search by looking through 55 issues of The Home, six years of Australia National Journal, four years of Australia Beautiful and 37 issues of Art in Australia. Remarkably, The Home alone featured 186 pages of Dupain’s photographs.

Within the pages of these journals, the full scope of Dupain’s stylistic experiments with portraiture can be found, from bold Surrealist-inspired montages using mirrors and glasses to faces revealed through striking interplays of sunlight and shadows. Despite stylistic variation, each photograph is enlivened by a sense of decisiveness and simplicity. In a 1940 edition of Australia National Journal, Dupain characterises studio effects in dismissive fashion – ‘fake sophistication, false effects and general dishonesty’ – preferring a less posed approach to portraiture. He declares, ‘my will must not be imposed upon the sitter … seizing upon the split second when personality, form and construction assume their climax and the greatest degree of unity is manifest, the exposure is made instantaneously’.