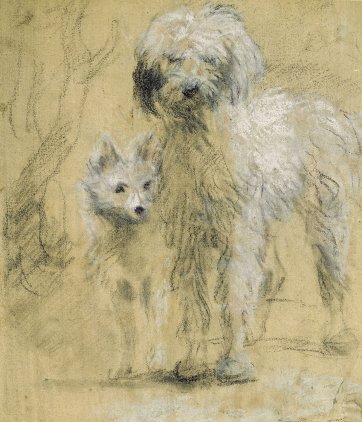

Thomas Gainsborough was one of eighteenth-century Britain’s most successful portraitists, but he paid a high price for his popularity. His private correspondence makes it clear that he chafed under the tyranny of his vain and wealthy sitters, whose incessant demands he blamed for stifling his creativity as an artist and demeaning his dignity as a gentleman. He also lamented that the need to earn his living from catering to an endless parade of ‘damnd Faces’ prevented him from pursuing his devotion to landscape, the branch of art he most loved, but that sadly did not pay. Yet, despite these feelings of profound frustration, Gainsborough nonetheless found the time, the energy and, perhaps most surprisingly, the desire to paint and draw more portraits of his family members than any other artist of his (or any earlier) period is known to have produced – nearly 50 likenesses in total. So how might we account for his seemingly paradoxical and decidedly unusual behaviour? And what can these pictures teach us about the painter, his world, and perhaps even ourselves?

Keep it in the family

by David Solkin, 21 January 2019

These were the principal questions I had in mind when I approached the National Portrait Gallery, London with the idea for Gainsborough’s Family Album several years ago, and since then I have learned not to expect any simple answers. Gainsborough’s portraits notoriously resist easy reading even when a great deal is known about their subjects and about the circumstances of the paintings’ production and reception. Also, as the introductory essays in the publication Gainsborough’s Family Album will at times make apparent, a critical consensus proves even harder to achieve where such historical evidence is lacking. Since all but one or two of his family pictures stayed entirely out of the public eye until long after the artist’s death, these portraits only rarely prompted written comments during his lifetime, or at least any that can now be traced. Compounding the problems caused by this lack of comment on the part of Gainsborough and his contemporaries is the concise economy of the pictorial rhetoric that he almost invariably adopted for depictions of his kinfolk. Given that he was not being paid for his labours, it is easy to understand why the painter’s main priorities tended to be simplicity and speed – although this has made the challenge facing later interpreters all the more difficult by leaving images that, as a rule, have little beyond the obvious to say about themselves. The fact is that they did not have to do more, if only for the simple reason that they were intended for an audience of relatives and friends, people who knew the sitters (and the painter) well. Not only are we not privy to that intimate knowledge, but today we can merely guess at what it must have been like to view Gainsborough’s ‘family album’ in its original setting. Largely confined in the eighteenth century to a small network of domestic households, the pictures now inhabit spaces of very different kinds across the world. Bringing these scattered works together under one roof presents a unique opportunity to reveal the full richness of their meanings, as individual objects and as a visual ensemble, and to see what further questions they suggest.

Whereas our own experience might lead us to expect Gainsborough’s pictures to conform to twenty-first-century ideas of privacy and informality, instead we find that in the main these representations are anything but casual, and that most are concerned less with expressing feelings of intimate attachment than with making claims to social status. The Artist with his Wife and Daughter was painted when the artist was no more than twenty years of age, and supplies the earliest evidence of the family’s determination to assert their claims to being the social equals of Gainsborough’s affluent patrons – quite a bold assertion, given the relatively humble status of the youthful artist and his wife’s problematic origins as the illegitimate daughter of a duke. In what may or may not be an indication of their subsequent marital difficulties, the couple would never again appear within the boundaries of a single canvas. Although now worn away by abrasions suffered in the past, the sheet of paper that Gainsborough is shown holding probably once bore the outlines of a landscape sketch. This, together with the prominence given the rural setting, indicates his personal and professional interest in landscape art.

In The Artist’s Daughters Chasing a Butterfly, Mary is shown restraining her sister as she reaches out towards a butterfly that has landed on a thistle, which threatens to prick her fingers with its sharp thorns. Originating in the seventeenth-century emblem books, this motif symbolised the dangers inherent in a child’s pursuit of its own thoughtless impulses, whilst also invoking the more general idea of the transience of human life and its pleasures. The introduction of this moral dimension, and the image’s obvious tenderness, are just two of several features that make this picture stand apart from the body of portraits from Gainsborough’s Ipswich period. No less unusual in this context is the large scale of the figures, their representation in motion, and the breadth and freedom of the artist’s brushwork – all of which indicate that the girls’ father was taking full advantage of the opportunities to experiment that only a private, uncommissioned portrait could offer. But the pressure to attend to paying customers probably also helps to explain why Gainsborough left the painting in an incomplete state.

If one primary purpose of the book, and of the exhibition it accompanies, is to offer a new perspective on Thomas Gainsborough the portraitist, a resonance with the sexual politics of today may well come as a surprise. Although Gainsborough was about as far from being a feminist as one could imagine, an admiration for strong women (albeit sometimes begrudgingly expressed) emerges as a striking feature of his correspondence, and informs more than one portrait of his female relations. His attitudes must have been shaped by personal experience, as Susan Sloman demonstrates in her essay. She explains how the two most important women in Gainsborough’s adult life, his wife Margaret and his sister Mary Gibbon, each played a key role in supporting the business side of his career. Their examples may in turn have prompted Gainsborough’s ambitions to educate his two daughters – also a Mary and a Margaret – so that they could earn their keep as professional landscape painters, though in the end they never did so. Instead, their visibility in the history of art derives chiefly from the part they played as the models for some of their father’s most experimental canvases. These pictures, as Ann Bermingham argues, have considerably more to tell us about Gainsborough’s aspirations than they do about the girls; yet even here – perhaps especially here – the sisters’ own voices can still be heard, intermingled with echoes of their mother’s, and of the family chorus at large. The conviction that artists act not alone, but in concert with the people closest to them, lies at the very heart of Gainsborough’s Family Album.

Extract from Gainsborough’s Family Album, which features over 50 beautifully reproduced portraits (available at npgshop.org.uk). The publication accompanies the first major exhibition of Gainsborough’s family portraits, showing at the National Portrait Gallery, London until 3 February 2019.

Related information

Portrait 61, Summer 2018/19

Magazine

Max Dupain's unknown portrait subjects, phrenologist Madame Sibly, Indigenous-European relationships, Thomas Gainsborough and more.

Sibly irresistible

Magazine article by Alexandra Roginski

Alexandra Roginski reveals a forceful feminist figure in the colonial period’s slippery science, phrenology.

The animating signature

Magazine article by Joanna Gilmour

Joanna Gilmore delights in the affecting drawings of Mathew Lynn.