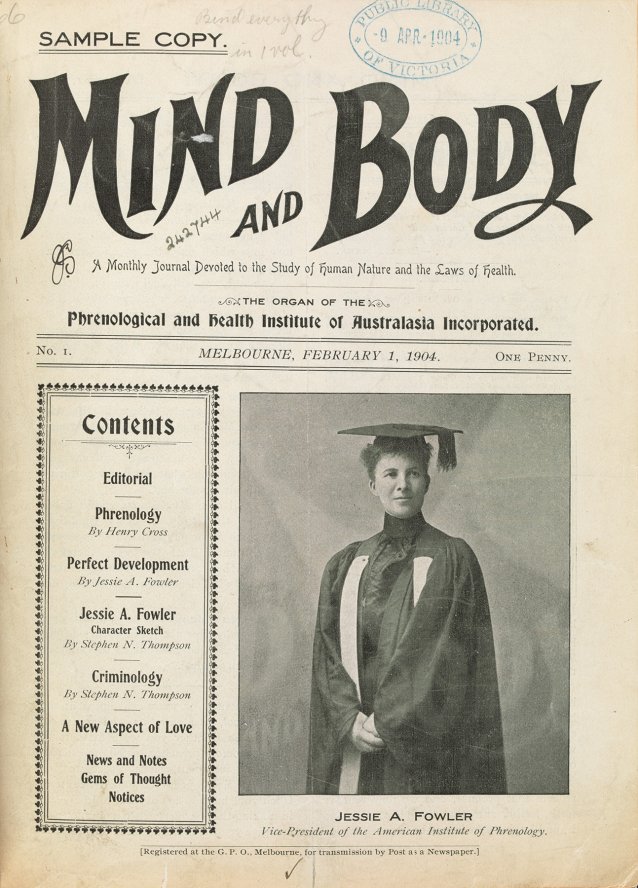

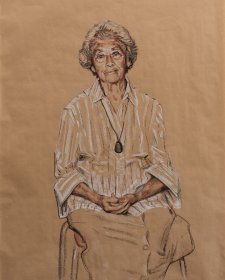

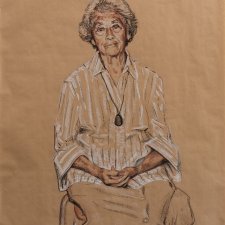

Jessie Fowler, a scion of the US phrenological Fowler empire, toured Victoria and New South Wales during the late 1880s, delivering lectures on head reading and physical culture complete with callisthenic demonstrations involving Indian clubs. Fowler embodied what the press and residents of affluent suburbs recognised as middle-class propriety, with mothers in Melbourne’s Brighton begging her to run gymnastics classes for their daughters. Her portrait on the cover of the Melbourne-based Mind & Body journal from 1904 captures this respectable intellectualism. While Sibly’s carte de visite invites onlookers to step closer and peer at her work of phrenological examination, and her dress and loose curls suggest sensuality, Fowler’s academic garb almost neutralises her gender, her clasped hands and sober hairstyle implying containment. And while Fowler earned fawning audiences, Sibly sometimes travelled under storm clouds.

Just months before her Bendigo brawl, Sibly marched to court in the Victorian town of Maryborough to seek the law’s assistance in separating from her de facto partner of three years, Henry Gardner. A tailor by trade, Gardner now lived from Sibly’s fame in his role as ‘manager’. He took money from audiences at the doors of her lectures. He also took money from Sibly more generally, stashing shillings in hiding places that included a coffee pot and a frying pan.

When Sibly attempted to break away from Gardner in a Maryborough hotel in the autumn of 1870, he beat her around the head so fiercely that the swelling kept her awake that night. The next evening, while washing, the lecturer told her partner that she would not go on to Ballarat. Gardner swore at Sibly and accused her of going into brothels. ‘He struck me, and knocked me down and jumped upon me in the bedroom’, she recounted.

‘I rushed to the door to get out, fearing he would kill me; he pushed me outside … with nothing but my skirt and stays, into the yard of the hotel.’ Before an assembled crowd of men and one laundrywoman, Gardner spat in his partner’s face. Sibly clutched at her whip but ‘he pulled it from me and beat me most unmercifully’.

The courtroom simmered with male justice, with the defence lawyer and magistrate making comic sport of Sibly’s ordeal. As part of a legal system that often fixated on female reputation when weighing up evidence, the magistrate assessed Sibly’s fallen virtue – the fact that she had left her own husband and now lived as a ‘paramour’. ‘The picture was not creditable to either party, but it was discreditable to one more than the other’, he concluded, referring with scorn to a letter that Gardner had sent to him outlining in ‘disgusting and painful detail’ how Sibly supposedly lured him from his wife.

The tailor’s bad character determined the case. For the magistrate, Gardner breached several codes of masculine conduct, including by ‘loafing’ on a woman’s income and by deigning to influence a man of the law through his filthy missive. ‘No matter how far this woman had fallen she was entitled to the protection of the law’, he concluded, ordering that Gardner ‘keep the peace’ in relation to Sibly.

Viewed against the context of this matter, Sibly’s decision to punch a man in the eyes in Bendigo can be interpreted as a tactic of theatrical violence used to deter potential abusers, if not to exact retribution against the male sex. It was just one of many attacks by Sibly. The week of the Bendigo event, she also threatened to horsewhip a former assistant. In 1874, she tried to employ this same weapon against a magistrate. In 1876, she knocked a paper clerk’s head into a wall when he presented her with a bill. And, in 1879, Sibly ended her decade of violence by beating two ‘jokers’ who harassed her at a hotel.

Sibly’s status as ‘Wonderful Woman’ therefore owed as much to her stage charisma as to her ability to navigate the perils of travel. She retired as one of the most successful colonial popular scientists of her time, finding peace in a rural living with Member of Parliament Alfred O’Connor in inland New South Wales. She still took to the road intermittently, and in 1885 toured with her daughter Blanche, who was known as ‘Zel the Magnetic Lady’.

When Sibly died of heart disease in the town of Drake in 1894, her death certificate recorded her status as a storekeeping matriarch with three grown children. Her supposed birthplace underscored an itinerant life – ‘At Sea Between England and France’.

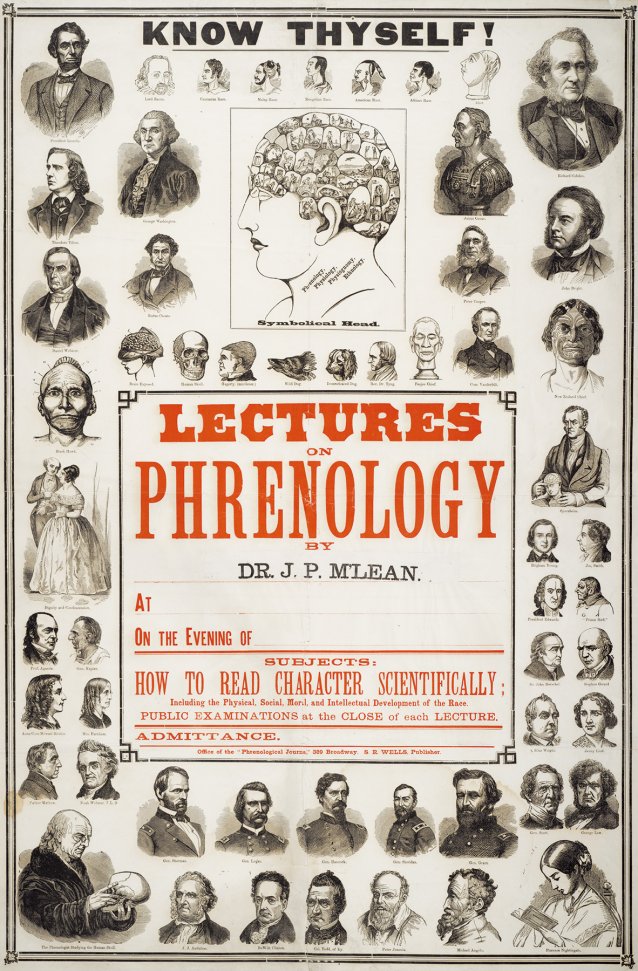

If the theatre in Sibly’s demeanour and dress already placed strain on her claims to scientific credibility during the 1870s, by the end of the century the term ‘phrenologist’ became increasingly associated with arcades and fairgrounds. A generalised form of divination inflected with exoticism became the bread-and-butter of phrenologists such as professors De Weldon and D’James, who briefly collaborated under their unlikely names in Victoria’s western district before airing an epistolary spat in the Colac Herald in 1895. ‘My study, taught to me by an Hindoo prince, in both ancient and modern sciences … crowns me as the king of all so called palmists’, wrote D’James. For some practitioners, phrenology simply became a cover for fortune telling, which was then illegal under vagrancy laws.

And while a few head readers managed to maintain a whiff of professionalism in the new century, repackaging themselves as occupational psychologists, many more lurked in the demi monde, crawling into the light during such scandals as the murderous attack by phrenologist and astrologer Emery Gordon Medor (not his real name). He turned the stomachs of a continent when he shot two of his neighbours in Melbourne’s Eastern Market, a colonnaded leisure space in the city’s centre.

Yet the murkiness of the phrenological realm also explains why such consultations continued to appeal to customers well into the twentieth century. With their fictitious names and tall stories, phrenologists invited their clients to revel with them in artifice and transcendence of the ordinary.