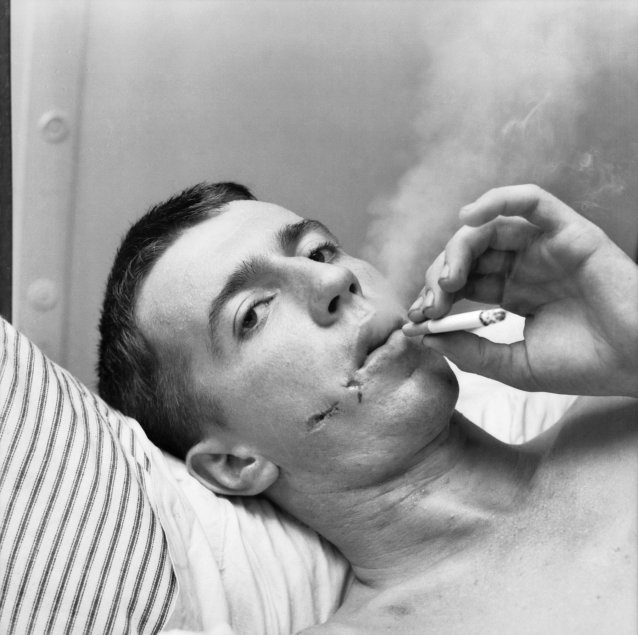

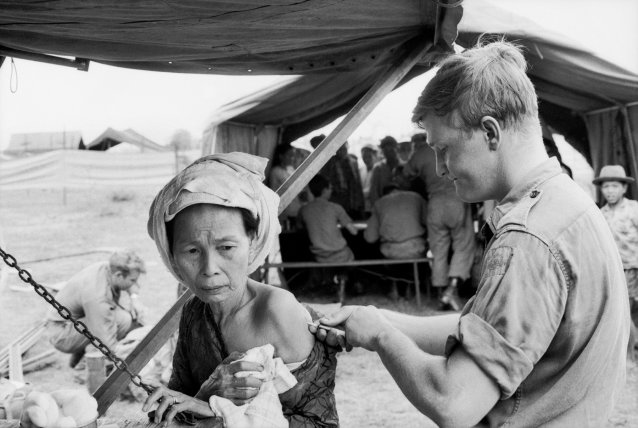

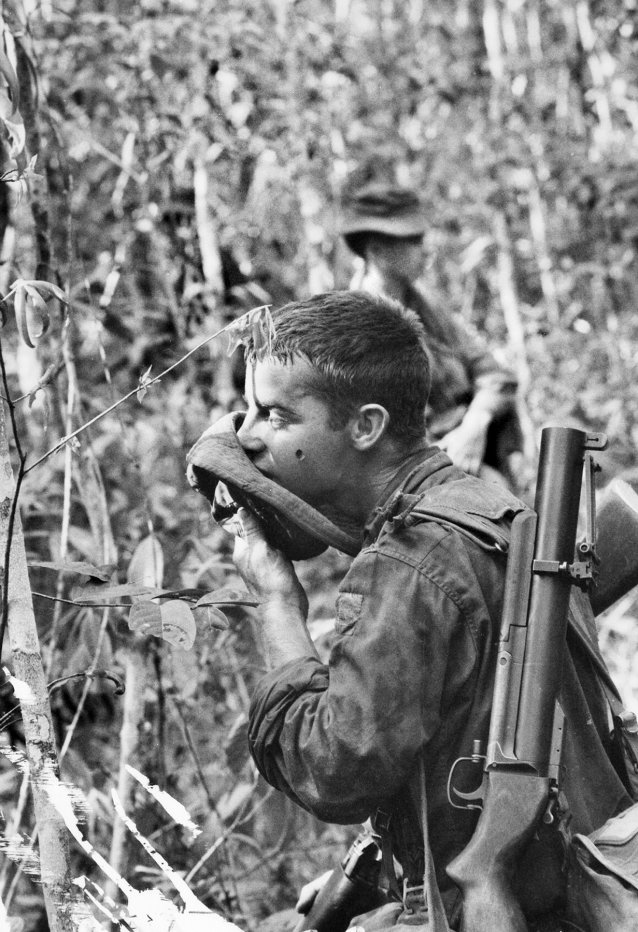

Half a century after the height of the conflict, the war in Vietnam is still noted for the level of media coverage it attracted, with many renowned civilian journalists and photographers making their names during its course. On the other side of the media equation, military public relations personnel were often characterised as blatant propagandists, presenting a view of the war that bore little resemblance to its operational reality. But to dismiss the military’s media in such reductionist terms is to overlook the skill of many who did this job. The photographic archive of the Australian Army’s Directorate of Public Relations (DPR) contains some fine examples of portraiture, which, despite being created for propaganda purposes, remain images that convey the authentic humanity of their subjects. Indeed, the work of these servicemen demonstrates that ‘propagandist image’ and ‘engaging portrait’ are not necessarily mutually exclusive categories.

The DPR’s purpose was explicit: ‘to build and maintain public understanding of and support for the Australian forces in Vietnam’. The brief sounds somewhat Orwellian, but should be considered in context. In simple terms, Australia didn’t go to war in Vietnam – Australia’s military did. There was no home front; Australian civilians were not subjected to rationing, the threat of air raids, or any society-wide contributions to a war effort. The war was something that was happening somewhere else, and unless a friend or loved one was deployed, it would be all too easy for ordinary Australians to pay no heed to the conflict or the people fighting in it.

Thus, the DPR sought to present the war such that it could be comprehended by the Australian public, with a view to promoting support for Australia’s armed forces, which in turn was a key factor in maintaining the morale of the military personnel serving overseas. There are two important points in regards to this brief. First, the DPR was a military organisation, not a media organisation. Accordingly, questions about whether the Vietnam War was morally or militarily justified were never explored. Secondly, although DPR photographers were directed to particular events or operations by their commanders, there was a lack of specific direction about what to photograph once they got there. There were no proscriptions – no precise instructions in terms of what could or could not be photographed.